OUTDOOR SPORTS AND GAMES

BY CLAUDE H. MILLER, PH.B.

XI

THE CARE OF CHICKENS

The best breed—Good and bad points of incubators—What to feed small chicks—A model chicken house

A pen of chickens gives a boy or girl an opportunity for keeping pets that have some real value. Whether there is much profit in poultry is a question, but it is at least certain that the more care you give them the better they pay. There is but little difference in the results obtained from the various breeds of chickens, but there is a great difference in the people who take care of them. It is very difficult to make poultry pay on a large scale. Nearly every poultry farm that has started as a business has failed to make a success. The surest way to make chickens pay is to have only a few. Then the table scraps and the worms and weed seeds they can pick up will supply them with practically all their feed and the time you give them need not be counted as expense.

There are sixty or seventy distinct breeds of poultry recognized by expert fanciers and from three to ten colours or varieties in many of these breeds. New ones are being added constantly. For example, a breed called Orpingtons was recently introduced from England and now has ten varieties or colours that are "standard." At the New York Poultry Show a record price of $2,500 was paid for the prize-winning hen of this breed. There is a style in chickens as well as in anything else. A new breed will always have a great many admirers at first, and great claims will be made for its superior qualities. The poultrymen who have stock and eggs to sell will secure high prices for their output. Very soon, however, the real value of a new breed will be known and it will be on the same basis as the older breeds.

A beginner had better start with some standard recognized breed and leave the

experimenting to some one else. One thing is certain: thoroughbreds will pay

better than mongrels. Their eggs are of more uniform size and colour, the stock

will be healthy and as a rule weigh a pound or two more than birds of uncertain

breeding. Thoroughbreds do not cost any more to feed or care for than the

mongrels and in every way are superior.

A beginner had better start with some standard recognized breed and leave the

experimenting to some one else. One thing is certain: thoroughbreds will pay

better than mongrels. Their eggs are of more uniform size and colour, the stock

will be healthy and as a rule weigh a pound or two more than birds of uncertain

breeding. Thoroughbreds do not cost any more to feed or care for than the

mongrels and in every way are superior.

Breeds of poultry are usually divided into three separate classes, depending on the place where the breed originated. They are the American, Asiatic, and Mediterranean strains. The leading American breed is the barred Plymouth Rock and for a beginner will probably be the best to start with.

Another very excellent American or general purpose breed is the White Wyandotte. They are especially valuable as broilers, as they make rapid growth while young. The Leghorns are the leading breed for eggs. They are "non-sitters" and, being very active, do not become overfat. Their small size, however, makes them poor table fowls and for this reason they are not adapted to general use. The Asiatic type, which includes Brahmas, Langshans, and Cochins, are all clumsy, heavy birds, which make excellent table fowl but are poor layers and poor foragers. Brahma roosters will frequently weigh fifteen pounds and can eat corn from the top of a barrel.

A beginner should never attempt to keep more than one kind of chickens. To get a start, we must either buy a pen of birds or buy the eggs and raise our own stock. The latter method will take a year more than the former, as the chicks we hatch this year will be our layers a year later. Sometimes a pen of eight or ten fowls can be bought reasonably from some one who is selling out. If we buy from a breeder who is in the business they will cost about five dollars a trio of two hens and a rooster. The cheapest way is to buy eggs and hatch your own stock. The usual price for hatching-eggs is one dollar for fifteen eggs. We can safely count on hatching eight chicks from a setting, of which four may be pullets. Therefore we must allow fifteen eggs for each four pullets we intend to keep the next year. The surplus cockerels can be sold for enough to pay for the cost of the eggs. If we have good luck we may hatch every egg in a setting and ten of them may be pullets. On the other hand, we may have only two or three chicks, which may all prove to be cockerels; so the above calculation is a fair average. If we start with eggs, we shall have to buy or rent some broody hens to put on the eggs. A good plan is to arrange with some farmer in the neighbourhood to take charge of the eggs and to set his own hens on them. I once made such an arrangement and agreed to give him all but one of the cockerels that hatched. I was to take all the pullets. The arrangement was mutually satisfactory and he kept and fed the chicks until they were able to leave the mother hen—about eight weeks. It is also possible to buy one-day-old chicks for about ten or fifteen cents apiece from a poultry dealer, but the safest way is to hatch your own stock.

The easiest way to make a large hatch all at one time is with an incubator. There are a number of very excellent makes advertised in the farm papers and other magazines and the prices are quite reasonable. An incubator holding about a hundred eggs will cost ten or twelve dollars. There are many objections to incubators which we can learn only from practical experience. We shall not average more than 50 per cent. hatches as a rule. That is to say, for every hundred eggs we set we must not count on hatching more than fifty chicks. Incubators are a constant care. The most important objection to an incubator is that it is against the rules of most fire insurance companies to allow it to be operated in any building that the insurance policy covers. If the automatic heat regulator fails to work and the heat in our incubator runs up too high we may have a fire. At any rate, we shall lose our entire hatch. The latter is also true if the lamp goes out and the eggs become too cool. I have made a great many hatches with incubators of different makes and my experience has been that we must watch an incubator almost constantly to have success with it.

The sure way to hatch chickens is with a broody hen, but at the same time incubators are perfectly satisfactory if run in a room where the temperature does not vary much (a cellar is the best place). With an incubator there is always a temptation to attempt to raise more chickens than we can care for properly. Overcrowding causes more trouble than any other one thing. It is better to have a dozen chickens well cared for than a hundred that are neglected.

Eggs for incubators will cost about five dollars a hundred [In the early 1900's.]. Of course if they are from prize-winning stock the cost will be several times this amount. Before placing any eggs in an incubator it should be run for two days to be sure that the heat regulator is in working order. The usual temperature for hatching is 103 degrees and the machine should be regulated for this temperature as it comes from the factory. Full directions for operating, as well as a thermometer, will come with the machine and should be studied and understood before we begin to operate it. As the hatch progresses, the heat will "run up," as it is called, and we shall need to understand how to regulate the thermostat to correct this tendency toward an increased temperature. The eggs in an incubator must be turned twice a day. To be sure that we do this thoroughly it is customary to mark the eggs before we place them in the machine. The usual mark is an "X" on one side of the egg and an "O" on the other written in lead pencil. In placing the eggs in the trays we start with all the "O" marks up, for instance, and at the time of the first turning leave all the "X's" visible, alternating this twice every day.

In order to operate an incubator successfully, we shall also need a brooder, which is really an artificial mother. There is a standard make of brooder costing five dollars that will accommodate fifty chicks. Brooders are very simple in construction and can be made at home. A tinsmith will have to make the heating drum. The rest of it is simply a wooden box with a curtain partition to separate the hot room from the feeding space. Ventilating holes must be provided for a supply of fresh air and a box placed at the bottom to prevent a draught from blowing out the lamp. In a very few days after we place the chicks in a brooder they should be allowed to go in and out at will. In a week or two we shall be able to teach them the way in, and then by lowering the platform to the ground for a runway we can permit them to run on the ground in an enclosed runway. On rainy days we must shut them in.

There is always a temptation to feed chicks too soon after they are hatched. We should always wait at least twenty-four hours to give them a chance to become thoroughly dry. The general custom of giving wet cornmeal for the first feed is wrong. Always feed chicks on dry food and you will avoid a great deal of sickness. An excellent first food is hard-boiled egg and corn bread made from cornmeal and water without salt and thoroughly baked until it may be crumbled. Only feed a little at a time, but feed often. Five times a day is none too much for two-week-old chicks.

One successful poultryman I am acquainted with gives, as the first feed, dog biscuit crushed. All the small grains are good if they are cracked so that the chicks can eat them. The standard mixture sold by poultry men under the name "chick food" is probably the best. It consists of cracked wheat, rye, and corn, millet seed, pinhead oatmeal, grit, and oyster shells. Do not feed meat to chicks until their pin feathers begin to show, when they may have some well-cooked lean meat, three times a week.

There is quite an art in setting a hen properly. They always prefer a dry, dark place. If we are sure that there are no rats around, there is no better place to set a hen than on the ground. This is as they sit in nature and it usually seems to be the case that a hen that steals her nest will bring out more chicks than one that we have coddled. Eggs that we are saving for hatching should be kept in a cool place but never allowed to freeze. They should be turned every day until they are set. Hens' eggs will hatch in about twenty-one days. The eggs that have failed to hatch at this time may be discarded. When we move a broody hen we must be sure that she will stay on her new nest before we give her any eggs. Test her with a china egg or a doorknob. If she stays on for two nights we may safely give her the setting. It is always better when convenient to set a hen where she first makes her nest. If she must be moved, do it at night with as little disturbance as possible. It is always a good plan to shut in a sitting hen and let her out once a day for feed and exercise. Do not worry if in your judgment she remains off the nest too long. The eggs require cooling to develop the air chamber properly, and as a rule the hen knows best.

Young chickens are subject to a great many diseases, but if they are kept dry and warm, and if they have dry food, most of the troubles may be avoided. With all poultry, lice are a great pest. Old fowls can dust themselves and in a measure keep the pest in check, but little chicks are comparatively helpless. The big gray lice will be found on a chick's neck near the head. The remedy for this is to grease the feathers with Vaseline® on the head and neck. The small white lice can be controlled by dusting the chicks with insect powder and by keeping the brooder absolutely clean. A weekly coat of whitewash to which some carbolic acid has been added will keep lice in check in poultry houses and is an excellent plan. Hen-hatched chicks are usually more subject to lice than those hatched In incubators and raised in brooders, as they become infected from the mother. Some people say that chicks have lice on them when they are hatched, but this is not so.

The first two weeks of a chick's life are the important time. If they are chilled or neglected they never get over it, but will develop into weaklings. There are many rules and remedies for doctoring sick chickens, but the best way is to kill them. This is especially so in cases of roup or colds. The former is a very contagious disease and unless checked may kill an entire pen of chickens. A man who raises 25,000 chickens annually once told me that "the best medicine for a sick chicken is the axe."

A very low fence will hold small chicks from straying away, but it must be absolutely tight at the bottom, as a very small opening will allow them to get through. Avoid all corners or places where they can be caught fast. The mesh of a wire fence must be fine. Ordinary chicken wire will not do.

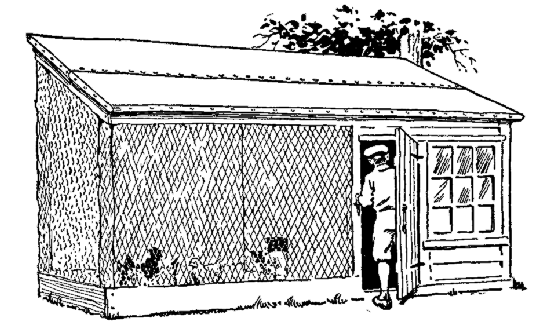

A home-made chicken coop built on the "scratching-shed"

plan

A home-made chicken coop built on the "scratching-shed"

plan A brooder that will accommodate fifty chicks comfortably for eight weeks will be entirely too small even for half that number after they begin to grow. As soon as they can get along without artificial heat, the chickens should be moved to a colony house and given free range. They will soon learn to roost and to find their way in and out of their new home, especially if we move away the old one where they cannot find it.

A chicken coop for grown fowls can be of almost any shape, size, or material, providing that we do not crowd it to more than its proper capacity. The important thing is to have a coop that is dry, easily cleaned and with good ventilation, but without cracks to admit draughts. A roost made of two by four timbers set on edge with the sharp corners rounded off is better than a round perch. No matter how many roosts we provide, our chickens will always fight and quarrel to occupy the top one. Under the roost build a movable board or shelf which may easily be taken out and cleaned. Place the nest boxes under this board, close to the ground. One nest for four hens is a fair allowance. Hens prefer to nest in a dark place if possible. A modern, up-to-date coop should have a warm, windproof sleeping room and an outside scratching shed. A sleeping room should be provided with a window on the south side and reaching nearly to the floor. A hotbed sash is excellent for this purpose. The runway or yard should be as large as our purse will permit. In this yard plant a plum tree for shade. The chickens will keep the plum trees free from the "curculio," a small beetle which is the principal insect pest of this fruit. This beetle is sometimes called "the little Turk" because he makes a mark on a plum that resembles the "star and crescent" of the Turkish flag.

Whether we can make our poultry pay for the trouble and expense of keeping them will depend on the question of winter eggs. It is contrary to the natural habits of chickens to lay in winter, and if left to themselves they will practically stop laying when they begin to moult or shed their feathers in the fall, and will not begin again until the warm days of spring. When eggs are scarce it will be a great treat to be able to have our own supply instead of paying a high price at the grocer's.

The fact that it is possible to get really fresh eggs in midwinter shows that with the proper care hens will lay. The average farm hen does not lay more than eighty eggs a year, which is hardly enough to pay for her feed. On the other hand, at an egg-laying contest held in Pennsylvania, the prize-winning pen made a record of 290 eggs per year for each hen. This was all due to better care and proper feed.

The birds were healthy pullets to begin with, they had warm food and warm drinking water throughout the winter, their coop was a bright, clean, dry place with an outside scratching shed. The grain was fed in a deep litter of straw to make them work to get it and thus to obtain the necessary exercise to keep down fat. The birds in this contest were all hatched early in March and were all through the moult before the cold weather came. Most of the advertised poultry feeds for winter eggs are a swindle. If we give the birds proper care we shall not require any drugs. It is an excellent plan to give unthreshed straw to poultry in winter. They will work to obtain the grain and be kept busy. The usual quantity of grain for poultry is at the rate of a quart of corn or wheat to each fifteen hens. A standard winter ration is the so-called hot bran mash. This is made from wheat bran, clover meal, and either cut bone or meat scraps. It will be necessary to feed this in a hopper to avoid waste and it should be given at night just before the birds go to roost, with the grain ration in the morning, which will keep them scratching all day. Always keep some grit and oyster shells where the chickens can get it; also feed a little charcoal occasionally.

A dust bath for the hens will be appreciated in winter when the ground is frozen. Sink a soap box in a corner of the pen and sheltered from rain or snow and fill it with dry road dust. Have an extra supply to fill up the box from time to time.

The best place for a chicken house is on a sandy hillside with a southern slope. A heavy clay soil with poor drainage is very bad. Six-foot chicken wire will be high enough to enclose the run. If any of the chickens persist in flying out we must clip the flight feathers of their wings (one wing, not both). Do not put a top board on the run. If a chicken does not see something to fly to, it will seldom attempt to go over a fence, even if it is quite low.

It is much better to allow chickens full liberty if they do not ruin our garden or flower beds or persist in laying in out of the way places where the eggs cannot be found.