OUTDOOR SPORTS AND GAMES

BY CLAUDE H. MILLER, PH.B.

VIII

NATURE STUDY

What is a true naturalist?—How to start a collection—Moth collecting—The Herbarium

There is nothing in the world that will bring more pleasure into the life of

a boy or girl than to cultivate a love for nature. It is one of the joys of life

that is as free as the air we breathe. A nature student need never be lonely or

at a loss for friends or companions. The birds and the bugs are his

acquaintances. Whenever he goes afield there is something new or interesting to

see and to observe. He finds—

There is nothing in the world that will bring more pleasure into the life of

a boy or girl than to cultivate a love for nature. It is one of the joys of life

that is as free as the air we breathe. A nature student need never be lonely or

at a loss for friends or companions. The birds and the bugs are his

acquaintances. Whenever he goes afield there is something new or interesting to

see and to observe. He finds—

"——tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, Sermons in stones and good in everything."

To love nature and her mysteries does not necessarily mean to be some kind of a queer creature running around with a butterfly net or an insect box. A true naturalist is simply a man or boy who keeps his eyes and ears open. He will soon find that nature is ready to tell him many secrets. After a time, the smell of the woods, the chirp of a cricket and the rustling of the wind in the pines become his pleasures.

The reason that people do not as a rule know more about nature is simply because their minds are too full of other things. They fail to cultivate the power of accurate observation, which is the most important thing of all. A practical start in nature study is to go out some dewy morning and study the first spider web you come across, noting how wonderfully this little creature makes a net to catch its food just as we make nets to catch fish, how the web is braced with tiny guy ropes to keep the wind from blowing it away in a way similar to the method an engineer would use in securing a derrick or a tall chimney. When a fly or bug happens to become entangled in its meshes, the spider will dart out quickly from its hiding place and if the fly is making a violent struggle for life will soon spin a ribbon-like web around it which will hold it secure, just as we might attempt to secure a prisoner or wild animal that was trying to make its escape, by binding it with ropes. A spider makes a very interesting pet and the surest way to overcome the fear that many people have of spiders is to know more about them.

There is no need to read big books or listen to dry lectures to study nature. In any square foot that you may pick out at random in your lawn you will find something interesting if you will look for it. Some tiny bug will be crawling around in its little world, not aimlessly but with some definite purpose in view. To this insect the blades of grass are almost like mighty trees and the imprint of your heel in the ground may seem like a valley between mountains. To get an adequate idea of the myriads of insects that people the fields, we should select a summer day just as the sun is about to set. The reflection of its waning rays on their wings will show countless thousands of flying creatures in places where, if we did not take the trouble to observe, we might think there were none.

There is one very important side to nature that must not be overlooked. It consists in knowing that we shall find a thousand things that we cannot explain to one that we fully understand. Education of any kind consists more in knowing when to say "I don't know and no one else knows either" than to attempt a foolish explanation of an unexplainable thing.

If you ask "why a cat has whiskers," or why and how they make a purring noise when they are pleased and wag their tails when they are angry, while a dog wags his to show pleasure, the wisest man cannot answer your question. A teacher once asked a boy about a cat's whiskers and he said they were to keep her from trying to get her body through a hole that would not admit her head without touching her whiskers.

No one can explain satisfactorily why the sap runs up in a tree and by some chemical process carries from the earth the right elements to make leaves, blossoms or fruit. Nature study is not "why?" It is "how." We all learn in everyday life how a hen will take care of a brood of chicks or how a bee will go from blossom to blossom to sip honey. Would it not also be interesting to see how a little bug the size of a pin head will burrow into the stem of an oak leaf and how the tree will grow a house around him that will be totally unlike the rest of the branches or leaves. That is an "oak gall." If you carefully cut a green one open you will find the bug in the centre or in the case of a dried one that we often find on the ground, we can see the tiny hole where he has crawled out.

Did you ever know that some kinds of ants will wage war on other kinds and make slaves of the prisoners just as our ancestors did in the olden times with human beings? Did you ever see a play-ground where the ants have their recreation just as we have ball fields and dancing halls? Did you ever hear of a colony of ants keeping a cow? It is a well-known fact that they do, and they will take their cow out to pasture and bring it in and milk it and then lock it up for the night just as you might do if you were a farm boy. The "ants' cow" is a species of insect called "aphis" that secretes from its food a sweet kind of fluid called "honey dew."

The ten thousand things that we can learn in nature could no more be covered in a chapter in this book than the same space could cover a history of the world. I have two large books devoted to the discussion of a single kind of flower, the "orchid." It is estimated that there are about two hundred thousand kinds of flowers, so for this subject alone, we should need a bookshelf over a mile long. This is not stated to discourage any one for of course no one can learn all there is to know about any subject. Most people are content not to learn anything or even see anything that is not a part of their daily life.

The only kind of nature study worth while is systematic. It is not safe to trust too much to the memory. Keep a diary and record in it even the most simple things for future reference. All sorts of items can be written in such a book. As it is your own personal affair, you need not try to make it a work of literary merit. Have entries such as these:

First frost—Oct. 3rd

First snow—3 inches Thanksgiving day

Skating—December 3rd

Weather clear and bright on Candlemas day, Feb. 2nd and therefore ground-hog saw his shadow

Heard crows cawing—Feb. 18th. Last year—Jan. 26th

Saw first robin—March 14th

Last snow—April 28th

There is scarcely anything in nature that is not interesting and in some way useful. Perhaps you will say "How about a bat?" As a matter of fact a bat is one of our best friends because he will spend the whole night catching mosquitoes. But some one will say "he flies into your hair and is covered with a certain kind of disgusting vermin." Did you ever know of a bat flying into any one's hair? And as for the vermin science tells us that they are really his favourite food so it is unlikely that he would harbour a colony of them very long.

The subject of snakes is one in which there is more misinformation than any other common thing. There are only three venomous kinds of snakes in America. They are the rattlesnake, copperhead and moccasin. All of them can be distinguished by a deep pit behind the eye, which gives them the name of "pit vipers." The general impression that puff adders, pilots, green snakes or water snakes are poisonous is absolutely wrong, and as for hoop snakes and the snake with a sting in his tail that all boys have heard about, they are absolutely fairy tales like "Jack and the Bean Stalk" or "Alice in Wonderland." We have all heard about black snakes eight or ten feet long that will chase you and wind themselves around your neck, but of the many hundreds of black snakes that a well known naturalist has seen he states that he never saw one that did not do its best to escape if given half a chance. Why so much misinformation about snakes exists is a mystery.

Nature study has recently been introduced into schools and it is a very excellent way to have the interesting things pointed out to us until our eyes are trained to see for ourselves. The usual methods of nature study may be roughly divided into, 1. Keeping pets. 2. Bird study. 3. Insect study. 4. Systematic study of flowers and plants. 5. Wild animal life. The basis of nature study consists in making collections. A collection that we have made for ourselves of moths or flowers, for instance, is far more interesting than a stamp or coin collection where we buy our specimens. If we go afield and collect for ourselves, the cost is practically nothing and we have the benefit of being in the air and sunshine.

One kind of collecting is absolutely wrong—that of birds' eggs, nests or even the birds themselves. Our little feathered songsters are too few now and most states have very severe penalties for killing or molesting them. A nature student must not be a lawbreaker.

The outfit for a butterfly or moth collection is very simple and inexpensive. We shall need an insect net to capture our specimens. This can be made at home from a piece of stiff wire bent into the shape of a flattened circle about a foot across. Fasten the ring securely to a broom handle and make a cheesecloth net the same diameter as the ring and about two feet deep.

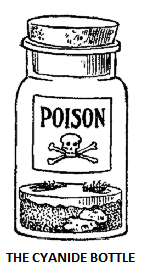

It is very cruel to run a pin through insects and to allow them slowly to

torture to death. An insect killer that is generally used is called "the cyanide

bottle." Its principle ingredient, cyanide of potassium is a harmless looking

white powder but it is the most deadly poison in the world. Unless a boy

or girl knows fully its terrible danger, they should never touch it or even

breathe its fumes. One of your parents or the druggist should prepare the

cyanide bottle for you and as long as you do not look into the bottle to watch

the struggles of a dying bug or in any way get any of the contents of the bottle

on your fingers, you are safe.

It is very cruel to run a pin through insects and to allow them slowly to

torture to death. An insect killer that is generally used is called "the cyanide

bottle." Its principle ingredient, cyanide of potassium is a harmless looking

white powder but it is the most deadly poison in the world. Unless a boy

or girl knows fully its terrible danger, they should never touch it or even

breathe its fumes. One of your parents or the druggist should prepare the

cyanide bottle for you and as long as you do not look into the bottle to watch

the struggles of a dying bug or in any way get any of the contents of the bottle

on your fingers, you are safe.

Take a wide-mouthed bottle made of clear glass and fit a cork or rubber stopper to it. Then wash the bottle thoroughly and dry it, finally polishing the inside with a piece of soft cloth or tissue paper. Place one ounce of cyanide of potassium into the bottle and pour in enough dry sawdust to cover the lumps of poison. Then wet some plaster of paris until it is the consistency of thick cream and quickly pour it over the sawdust, taking care that it does not run down the sides or splash against the bottle. Place the bottle on a level table and very soon the plaster of paris will set and harden into a solid cake.

Sufficient fumes from the cyanide will come up through the plaster to poison the air in the bottle and to kill any living thing that attempts to breathe it. As you capture your specimens of moths, bugs or butterflies afield you place them into the bottle, and as soon as they are dead, you remove them; fold them carefully in stiff paper and store them in a paper box or a carrying case until you get home. They should then be mounted on boards or cork sheets, labelled carefully with the name of the specimen, date and place of capture and any other facts that you may wish to keep.

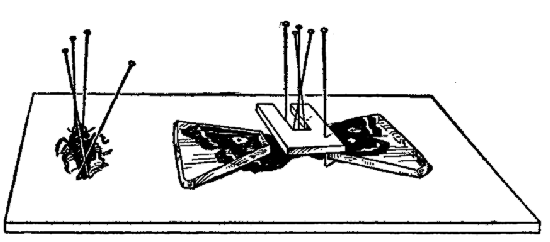

How insects are spread to dry them in a natural

position

How insects are spread to dry them in a natural

position Considerable skill is required to mount insects properly and in a life-like position. If they are out of shape you must "spread" them before they dry out. Spreading consists in holding them in the proper position by means of tiny bits of glass and pins until they are dry.

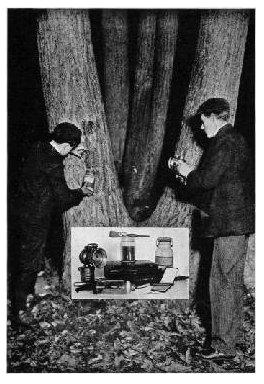

As moths are, as a rule, night-flying creatures the collector will either obtain them in a larval stage, or will adopt the method of "sugaring," one of the most fascinating branches of nature study. A favourable locality is selected, a comparatively open space in preference to a dense growth, and several trees are baited or sugared to attract the moths when in search of food. The sugar or bait is made as follows: Take four pounds of dark brown sugar, one quart of molasses, a bottle of stale ale or beer, four ounces of Santa Cruz rum. Mix and heat gradually. After it is cooked for five minutes allow it to cool and place in Mason jars. The bait will be about the consistency of thick varnish.

Just before twilight the bait should be painted on a dozen or more trees with a strip about three inches wide and three feet long. You will need a bull's-eye lantern or bicycle lamp and after dark, make the rounds of your bait and cautiously flash the light on the baited tree. If you see a moth feeding there, carefully bring the cyanide bottle up and drop him into it. Under no circumstances, clap the bottle over the specimen. If you do the neck of the bottle will become smeared with the bait and the moth would be daubed over and ruined. You will soon have all the specimens that you can care for at one time and will be ready to go home and take care of them.

The moths are among the most beautiful creatures in nature and a reasonably complete collection of the specimens in your neighbourhood will be something to be proud of.

The plant and flower collector should combine his field work with a study of botany. Like most subjects in school books, botany may seem dry and uninteresting but when we learn it for some definite purpose such as knowing the wild flowers and calling them our friends, we must accept the few strange words and dry things in the school work as a little bitter that goes with a great deal of sweet.

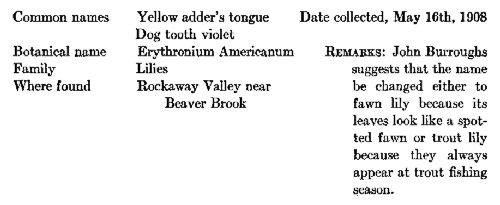

A collection of dried plants is called an herbarium. It is customary to take the entire plant as a specimen including the roots. Separate specimens of buds, leaves, flowers and fruit taken at different seasons of the year will make the collection more complete. Specimens should be first pressed or flattened between sheets of blotting paper and then mounted on sheets of white paper either by glue or by strips of gummed paper.

After a flower is properly identified, these sheets should be carefully numbered and labelled and a record kept in a book so that we can readily find a specimen without unnecessarily handling the specimen sheets. The sheets should be kept in heavy envelopes of manila paper and placed in a box just the size to hold them. The standard or museum size of herbarium sheets is 11 1/2 x 16 1/2 inches. Specimens of seaweed or leaves can be kept in blank books.

A typical label for plants or flowers should be as follows:

A boy or girl living in a section where minerals are plentiful, can make a very interesting collection of stones and mineral substances, especially crystals. This should be taken up in connection with school work in chemistry and mineralogy. To determine the names of minerals is by no means as easy as that of flowers or animals. We shall need to understand something of blow-pipe analysis. As a rule a high school pupil can receive a great deal of valuable instruction and aid from one of his teachers in this work. Mineral specimens should be mounted on small blocks or spindles using sealing wax to hold them in place.

There are unlimited possibilities in nature for making collections. Shells, mosses, ferns, leaves, grasses, seeds, are all interesting and of value. An observation beehive with a glass front which may be darkened will show us the wonderful intelligence of these little creatures. The true spirit of nature study is to learn as much as we can of her in all of her branches, not to make a specialty of one thing to the neglect of the rest and above all not to make work of anything.

We see some new side to our most common things when we once learn to look for it. Not one person in ten thousand knows that bean vines and morning glories will twine around a pole to the right while hop vines and honeysuckle will go to the left and yet who is there who has not seen these common vines hundreds of times?

No one can give as an excuse that he is too busy to study nature. The busiest men in national affairs have had time for it and surely we with our little responsibilities and cares can do so too. I once went fishing with a clergyman and I noticed that he stood for a long time looking at a pure white water lily with beautiful fragrance that grew from the blackest and most uninviting looking mud that one could find. The next Sunday he used this as an illustration for his text. How many of us ever saw the possibility of a sermon in this common everyday sight?