THE COMPLETE GOLFER

By Harry Vardon

CHAPTER XIION BEING BUNKERED

The philosopher in a bunker - On making certain of getting out - The folly of trying for length - When to play back - The qualities of the niblick - Stance and swing - How much sand to take - The time to press - No follow-through in a bunker - Desperate cases - The brassy in a bunker - Difficulties through prohibited grounding - Play straight when length is imperative - Cutting with the niblick.

This is a hateful subject, but one which demands the most careful and unprejudiced consideration, for are not even the best of us bunkered almost daily? There is nothing like the bunkers on a golf links for separating the philosophical from the unphilosophical among a golfing crowd, and when a representative of each section is in a bunker at the same time it is heavy odds on the philosopher winning the hole. There are two respects in which he differs from his opponent at this crisis in his golfing affairs. He does not become flurried, excited, and despondent, and give the hole up for lost with a feeling of disgust that he had committed the most unpardonable sin. He remembers that there are still various strokes to be played before the hole is reached, and that it is quite possible that in the meantime his friend may somewhere lose one and enable him to get on level terms again. When two players with plus handicaps are engaged in a match, a bunkered ball will generally mean a lost hole, but others who have not climbed to this pinnacle of excellence are far too pessimistic if they assume that this rule operates in their case also. The second matter in which the philosophic golfer rises superior to his less favoured[Pg 132] brother when there is a bunker stroke to be played, is that he fully realises that the bunker was placed there for the particular purpose of catching certain defective shots, and that the definite idea of its constructors was that the man who played such a shot should lose a stroke as penalty for doing so every time.

It is legitimate for us occasionally to put it to ourselves that those constructors did not know the long limits of our resource nor the craftiness we are able to display when in a very tight corner, and that therefore, if we find a favorable opportunity, we may cheat the bunker out of the stroke that it threatens to take from us. But this does not happen often. When the golfer has brought himself to realize that, having played into a bunker, he has lost a stroke or the best part of one, and accepts the position without any further ado, he has gone a long way in the cultivation of the most desirable properties of mind and temperament with which any player of the game can be endowed. This man, recognizing that his stroke is lost, when he goes up to his ball and studies the many difficulties of its situation, plays for the mere purpose of getting out again, and probably putting himself on the other side in that one stroke which was lost. It does not matter to him if he only gets two yards beyond the bunker—just far enough to enable him to take his stance and swing properly for the next shot. Distance is positively no object whatever, and in this way he insures himself against further loss, and goes the right way to make up for his misfortune.

Now, what does the other man do in like circumstances? Unreasonably and foolishly he refuses to accept the inevitable, and declines to give up the idea of getting to a point a hundred yards or more in front with his next shot, which he would have reached if he had not been in the bunker. He seems to think that the men who made the bunkers did not know their business. Having been bunkered, he says to himself that it is his duty to himself and to the game to make up for the stroke which was lost by supremely brilliant[Pg 133] recovery under the most disheartening circumstances. He insists that the recovery must be made here in the bunker, and thereafter he will progress as usual. It never occurs to him that it would be wiser and safer to content himself with just getting out the hazard, and then, playing under comparatively easy and comfortable conditions, to make his grand attempt at recovering the lost stroke. He would be much more likely to succeed. A stroke lost or gained is of equal value at any point on the route from the tee to the hole, and it is a simple fact, too often never realised, that a long putt makes up for a short drive, and a mashie [3 Iron] shot laid dead for a previous stroke from which the ball was trapped in the bunker. But the unphilosophic gentleman, who is ignorant of, or tries to resist, these truths, feels that his bunkered stroke must be compensated for by the next one or never.

What is the result? Recklessly, unscientifically, even ludicrously, he fires away at the ball in the bunker with a cleek or an iron or a mashie, striving his utmost to get length, when, with the frowning cliff of the bunker high in front of him and possibly even overhanging him, no length is possible. At the first attempt he fails to get out. His second stroke in the hazard shares the same fate. With a third or a fourth his ball by some extraordinary and lucky chance may just creep over the top of the ridge. How it came to do so when played in this manner nobody knows. The fact can only be explained by the argument that if you keep on doing the same thing something is sure to happen in the end, and it is a sufficient warning to these bunkered golfers that the gods of golf have so large a sense of justice and of right and wrong that by this time the hole has for a certainty been lost.

The slashing player who wants to drive his long ball out of the bunker very rarely indeed gets even this little creep over the crest until he has played two or three more, and is in a desperate state of lost temper. An alternative result to his efforts comes about when he has played these three or four more, and his ball is, if anything,[Pg 134] more hopelessly bunkered than ever. All sense of what is due to the game and to his own dignity is then suddenly lost, and a strange sight is often seen. Five, six, and seven more follow in quick succession, the man's arms working like the piston of a locomotive, and his eyes by this time being quite blinded to the ball, the sand, the bunker, and everything else. As an interesting feature of what we might call golfing physiology, I seriously suggest that players of these habits and temperament, when they begin to work like a steam-engine in the bunker, do not see the ball at all for the last few strokes. The next time they indulge in their peculiar performance, let them ask themselves immediately afterwards whether they did see it or not, and in the majority of cases they will have to answer in the negative. When it is over, a few impious words are uttered, the ball is picked up, and there is a slow and gloomy march to the next tee, from which it is unlikely that a good drive will be made. The nervous system of the misguided golfer has been so completely upset by the recent occurrences, that he may not recover his equanimity until several more strokes have been played, or perhaps until the round is over and the distressing incidents have at last passed from his mind.

This has been a long story about a thing that happens on most links every day, but the moral of it could hardly have been emphasized properly or adequately if it had been told in fewer words, or if the naked truth had been wrapped up in any more agreeable terms. The moral obviously is, that the golfer on being bunkered must concentrate his whole mind, capabilities, and energies on getting out in one stroke, and must resolutely refrain from attempting length at the same time, for, in nine cases out of ten, length is impossible. There are indeed occasions when so light a sentence has been passed by the bunker on the erring ball that a long shot is practicable, but they are very rare, and come in an entirely different category from the average bunkered ball, and we will consider them in due course.[Pg 135] On the other hand, there are times when it is manifestly impossible even to get to the other side of the bunker in a single stroke, as when the ball is tucked up at the foot of a steep and perhaps overhanging cliff. Still the man must keep before himself the fact that his main object is to get out in the fewest strokes possible, and in a case of this sort he may be wise to play back, particularly if it is a medal round that he is engaged upon. If he plays back he is still in the running for his prize if his golf has been satisfactory up to this point, for an addition of two strokes to his score through such an accident, though a serious handicap, is seldom a hopeless one. If he does not play back his chance of victory may disappear entirely at this bunker. His instinct tells him that it probably will do so. Which then is the wiser and better course to take?

Now, then, let us consider the ways and means of getting out of bunkers, and take in our hands the most unpopular club that our bags contain. We never look upon the niblick with any of that lingering affection which is constantly bestowed on all the other instruments that we possess, as we reflect upon the splendid deeds that they have performed for us on many memorable occasions. The niblick revives only unpleasant memories, but less than justice is done to this unfortunate club, for, given fair treatment, it will accomplish most excellent and remunerative work in rescuing its owner from the predicaments in which his carelessness or bad luck in handling the others has placed him. There is little variety in niblicks, and therefore no necessity to discourse upon their points, for no professional is ever likely to stock a niblick for sale that is unequal to the performance of its peculiar duties. It has rougher and heavier work to do than any other club, and more brute force is requisitioned in employing it than at any other time. Therefore the shaft should be as strong as it is possible for it to be, and it should be so stiff that it will not bend under the most severe pressure. The head should be rather small and round,[Pg 136] with plenty of loft upon it, and very heavy. A light niblick is useless.

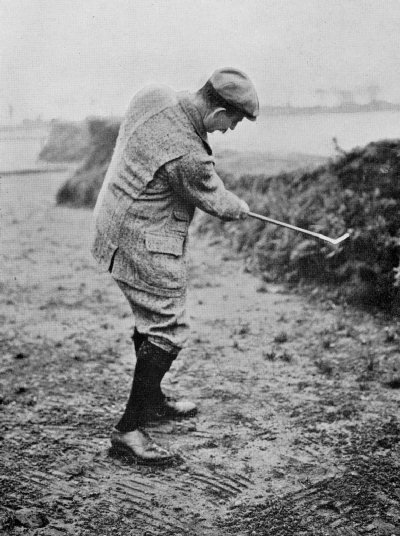

PLATE LIII. THE NIBLICK IN A BUNKER. TOP OF AN ORDINARY STROKE WHEN IT IS INTENDED TO TAKE MUCH SAND

PLATE LIV. "WELL OUT!" FINISH OF AN ORDINARY STROKE IN A BUNKER WHEN MUCH SAND IS TAKEN. THE BALL MAY BE SEEN RISING ABOVE THE BUNKER

PLATE LV. ANOTHER BUNKER STROKE. TOP OF THE SWING WHEN INTENDING TO TAKE THE BALL CLEANLY AND WITH A LITTLE CUT

It's difficult to tell what's going to be the best stance for a niblick shot in a bunker, inasmuch as it so frequently happens that this is governed by circumstances which are quite beyond the golfer's control. He must learn to adapt himself in the best possible manner to the conditions in which he finds himself, and it will often happen that he is cramped for space, he may be unable to get a proper or comfortable place for one or both of his feet, or he may be obliged to stand with one foot—generally the left one—considerably above the other. But when there are none of these difficulties besetting him, it may be said that generally the stance most suited to a stroke with the niblick is similar to that which would be taken for a long shot with an iron, except perhaps that the player should stand a little nearer to the ball, so that he may be well over it while making his swing. The most important respect in which the swing differs from that of the iron is that the club is brought up much straighter. By this I mean that the head of the club should not be allowed to come round quite so much, but throughout its course should be kept as nearly as possible overhanging what we have been calling the A line. The swing, indeed, is much more of what I call an upright character than that of any other stroke in the game, and at the top of it, the blade having passed over the right shoulder and the golfer's head, the shaft should be nearly horizontal and right over the back of the head, an example of which may be seen in Plate LIII., where I have a fairly good lie, but am rather badly bunkered for all that, being only a couple of feet from the base of a high and tolerably steep bank.

If there is such a thing as an average bunker shot, this is the one, and I am now describing the method of dealing with cases of this and similar character. There must be no thought of hitting the ball cleanly with the club in a case of[Pg 137] this kind, or in any other than the most exceptional situations or emergencies when bunkered. The club must hit the sand, and the sand must move the ball, but the iron blade of the niblick must hardly ever come into contact with the ball. To prevent its doing so, and to ensure the blade getting underneath sufficiently to lift the ball up at the very sharp angle that is necessary if it is to surmount the obstruction in front of it, the sand should be struck at a point fully two inches behind the ball. If the sand is exceedingly light and dry, so that it offers very little resistance to the passage of the club, this distance may be slightly increased, or it may be diminished if the lie in the bunker is very heavy, consisting of gravel or clay. It is on this point, so far behind the ball, that the eye must, of course, be sternly and rigidly fixed, and it is a duty which the beginner frequently finds most difficult to fulfil. In the downward swing the club should be brought on to the spot indicated with all the speed and force of which the golfer is capable. At other times he may have had a yearning to press, which he has with difficulty stifled. He may make up for all these ungratified desires by pressing now with all the strength in his body, and the harder the better so long as he keeps his eye steadily fixed on that point behind the ball and is sure that his muscular efforts will not interfere with his accuracy. After all, the latter need not be quite so fine in this case as in the many others that we have already discussed, for an eighth of an inch one way or the other does not much matter in the case of a niblick shot where there are two inches of sand to plough through. Swing harder than ever on to the sand, with the knowledge that the swing will end there, for a follow-through is not desired and would in many cases be impossible. When the heavy blade goes crash into the sand and blows it, and the ball with it, up into the air as if the electric touch had been given to an explosive mine, the club has finished its work, and when the golfer is at rest again and is surveying the results of his labours—with his eyes, let[Pg 138] us hope, directed to the further side of the hazard—the blade will still remain in the cavity that it has made in the floor of the bunker. If any attempt were made to follow through, it is highly probable that sufficient sand would not be taken to make the ball rise up soon enough.

However, the more one reflects upon bunkers and niblicks, the more does one feel that the circumstances must govern the method of playing each of these strokes, and there is no finer field for the display of the golfer's judgment and resource than this. The next best accomplishment to the negative one of avoiding bunkers is that of getting out again with the least waste of strokes and distance; and, indeed, I should say that the man who is somewhat addicted to being bunkered but invariably makes a good recovery, is at least on level terms with another who is in trouble not quite so frequently but who suffers terribly when he is. The golden rule—I say it once again—is to make certain of getting out; but now that I have sufficiently emphasised this point, I am ready to consider those few occasions when it appears a little weak and unsatisfactory. Certainly there are times, as we all know, when the enemy, having had matters his own way at a hole, it will not be of the slightest use merely to scramble out of a bunker in one stroke. The case is so desperate that a stroke that will carry the ball for perhaps 100 or 120 yards is called for. Such a necessity does not affect my rule as to making certain of getting out, for in practical golf one cannot take any serious account of emergencies of this kind. But there are times when every player must either attempt the shot that most frequently baffles his superiors, or forthwith give up the hole, and it is not in human nature to cave in while the faintest spark of hope remains. In thus attempting the impossible, or the only dimly possible, we are sometimes led even to take the brassy in a bunker. In a case of this sort, of course, everything depends on the lie of the ball and its distance from the face of the bunker. When it is a shallow pot bunker,[Pg 139] the shot is often practicable, and sometimes when one is bunkered on a seaside course the hazard is so wide that there is time for the ball to rise sufficiently to clear the obstruction. But the average bunker on an inland course, say four feet high with only six feet of sand before it, presents few such loopholes for escape. The difficulty of playing a shot from a bunker when any club other than the niblick, such as the brassy, is chosen with the object of obtaining length by hitting the ball clean, is obviously increased by the rule which prohibits the grounding of the club in addressing. To be on the safe side, the sole of the club is often kept fully an inch and a half above the sand when the address is being made, and this inch and a half has to be corrected down to an eighth in the forward swing, for of all shots that must be taken accurately this one so full of difficulty must be. In making his correction the man is very likely to overdo it and strike the sand before the ball, causing a sclaff, or, on the other hand, not to correct sufficiently when the only possible result would be a topped ball and probably a hopeless position in the hazard. It is indeed a rashly speculative shot, and one of the most difficult imaginable. It comes off sometimes, but it is a pure matter of chance when it does, and the lucky player is hardly entitled to that award of merit which he may fancy he deserves.

When the situation of the bunkered ball is unusually hopeful, and there does really seem to be a very fair prospect of making a good long shot, I think it generally pays best to play straight at the hazard, putting just a little cut on the ball to help it to rise, and employing any club that suggests itself for the purpose. I think, in such circumstances, that it pays best to go straight for the hazard, because, if length is urgently demanded, what is the use of playing at an angle? Again, though there is undoubtedly an advantage gained by taking a bunker crossways, and thus giving the ball more time to rise, the advantage is often greatly exaggerated in the golfer's mind. When a ball is[Pg 140] bunkered right on the edge of the green, it is sometimes best to try to pick it up not quite but almost cleanly with the niblick or mashie, in the hope that one more stroke afterwards will be sufficient either to win or halve the hole, whereas an ordinary shot with the niblick would not be likely to succeed so well. If, after due contemplation of all the heavy risks, it is decided to make such an attempt, the stroke should be played very much after the fashion of the mashie approach with cut. I need hardly say that such a shot is one of the most difficult the golfer will ever have occasion to attempt. The ordinary cut mashie stroke is hard to accomplish, but the cut niblick is harder still. I have already given directions for the playing of such shots, and the remainder must be left to the golfer's daring and his judgment.