THE COMPLETE GOLFER

By Harry Vardon

CHAPTER XIVCOMPLICATED PUTTS

Problems on undulating greens—The value of practice—Difficulties of calculation—The cut stroke with the putter—How to make it—When it is useful—Putting against a sideways slope—A straighter line for the hole—Putting down a hill—Applying drag to the ball—The use of the mashie on the putting green—Stymies—When they are negotiable and when not—The wisdom of playing for a half—Lofting over the stymie—Running through the stymie—How to play the stroke, and its advantages—Fast greens for fancy strokes—On gauging the speed of a green.

Now we will consider those putts in which it is not all plain sailing from the place where the ball lies to the hole. The line of the putt may be uphill or it may be downhill, or the green may slope all the way from one side to the other, or first from one and then the other. There is no end to the tricks and difficulties of a good sporting green, and the more of them the merrier. The golfer's powers of calculation are now in great demand.

Take, to begin with, one of the most difficult of all putts—that in which there is a more or less pronounced slope from one side or the other, or a mixture of the two. In this case it would obviously be fatal to putt straight at the hole. Allowances must be made on one side or the other, and sometimes they are very great allowances too. I have found that most beginners err in being afraid of allowing sufficiently for the slope. They may convince themselves that in order to get near the hole their ball should be a yard or so off the straight line when it is half-way along its course, and yet, at the last instant, when they make the stroke their nerve and resolution seem to fail them, and they point the[Pg 151] ball but a few inches up the slope, with the result that before it reaches the hole it goes running away on the other side and comes to a standstill anything but dead. Putting practice on undulating greens is very valuable, not so much because it teaches the golfer exactly what allowance he should make in various cases, but because it helps by experience to give him the courage of his convictions. It is impossible to give any directions as to the precise allowance that should be made, for the simple reason that this varies in every case. The length of the putt, the degree of slope, and the speed of the green, are all controlling factors. The amount of borrow, as we term it, that must be taken from the side of any particular slope is entirely a matter of mathematical calculation, and the problem will be solved to satisfaction most frequently by the man who trains himself to make an accurate and speedy analysis of the controlling factors in the limited amount of time available for the purpose. The putt is difficult enough when there is a pronounced slope all the way from one particular side, but the question is much more puzzling when it is first one and then the other and then perhaps a repetition of one or both. To begin with, there may be a slope of fifteen degrees from the right, so the ball must go away to the right. But a couple of yards further on this slope may be transformed into one of thirty degrees the other way, and after a short piece of level running the original slope, but now at twenty degrees, is reverted to. What in the name of golf is the line that must be taken in a tantalising case of this kind? It is plain that the second slope if it lasts as long as the first one more than neutralises it, being steeper, so that instead of borrowing from the first one we must start running down it in order to tackle the second one in good time. But the third slope again, to some extent, though not entirely, neutralises the second, and this entirely upsets the calculation which only included the first two. It is evident that the first and third hold the advantage between them, and that in such a case as[Pg 152] this we should send the ball on its journey with a slight borrow from the first incline with which it had to contend. As I have just said, in these complicated cases it is a question of reckoning pure and simple, and then putting the ball in a straightforward manner along the line which you have decided is the correct one.

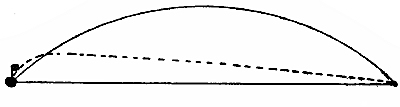

But there are times when a little artifice may be resorted to, particularly in the matter of applying a little cut to the ball. There is a good deal of billiards in putting, and the cut stroke on the green is essentially one which the billiard player will delight to practise. But I warn all those who are not already expert at cutting with the putter, to make themselves masters of the stroke in private practice before they attempt it in a match, because it is by no means easy to acquire. The chief difficulty that the golf student will encounter in attempting it will be to put the cut on as he desires, and at the same time to play the ball with the proper strength and keep on the proper line. It is easy enough to cut the ball, but it is most difficult, at first at all events, to cut it and putt it properly at the same time. For the application of cut, turn the toe of the putter slightly outwards and away from the hole, and see that the face of the club is kept to this angle all the way through the stroke. Swing just a trifle away from the straight line outwards, and the moment you come back on to the ball draw the club sharply across it. It is evident that this movement, when properly executed, will give to the ball a rotary motion, which on a perfectly level green would tend to make it run slightly off to the right of the straight line along which it was aimed. Here, then, the golfer may arm himself with an accomplishment which may frequently prove of valuable service. He may dodge a stymie or circumvent an inconvenient piece of the green over which, without the cut, the ball would have to travel. But most frequently will the accomplished putter find the cut of use to him when there is a pronounced slope of the green from the right-hand side of[Pg 153] the line of the putt. In applying cut to the ball in a case of this kind, we are complicating the problem by the introduction of a fourth factor to the other three I have named, but at the same time we are diminishing the weight of these others, since we shall enable ourselves to putt more directly at the hole. Suppose it is a steep but even slope all the way from the ball to the hole. Now, if we are going to putt this ball in the ordinary manner without any spin on it, we must borrow a lot from the hill, and, as we shall at once convince ourselves, the ball must be at its highest point when it is just half-way to the hole. But we may borrow from the slope in another way than by running straight up it and straight down again. If we put cut on the ball, it will of itself be fighting against the hill the whole way, and though if the angle is at all pronounced it may not be able to contend against it without any extra borrow, much less will be required than in the case of the simple putt up the hill and down again. Now it must be borne in mind that it is a purely artificial force, as it were, that keeps the ball from running down the slope, and as soon as the run on the ball is being exhausted and the spin at the same time, the tendency will be not for the ball to run gradually down the slope—as it did in the case of the simple putt without cut—but to surrender to it completely and run almost straight down. Our plan of campaign is now indicated. Instead of going a long way up the hill out of our straight line, and having but a very vague idea of what is going to be the end of it all, we will neutralise the effect of the slope as far as possible by using the cut and aim to a point much lower down the hill—how much lower can only be determined with knowledge of the particular circumstances, and after the golfer has thoroughly practised the stroke and knows what he can do with it. And instead of settling upon a point half-way along the line of the putt as the highest that the ball shall reach, this summit of the ascent will now be very much nearer to the hole, quite close to it in[Pg 154] fact. We putt up to this point with all the spin we can get on the ball, and when it reaches it the forward motion and the rotation die away at the same time, and the ball drops away down the hill, and, as we hope, into the hole that is waiting for it close by. Now, after all this explanation, it may really seem that by using the cut in a case of this kind we are going about the job in the most difficult manner, but when once the golfer has made himself master of this cut stroke, and has practised this manner of attacking slopes, he will speedily convince himself that it is the easier and more reliable method—certainly more reliable. It seems to be a great advantage to be able to keep closer to the straight line, and the strength can be more accurately gauged. The diagram which I have drawn on this page shows relatively the courses taken by balls played in the two different styles, and will help to explain my meaning. The slope is supposed to be coming from the top of the page, as it were, and the plain curved line is the course taken by the ball which has had no cut given to it, while that which is dotted is the line of the cut ball. I am giving them both credit for having been played with the utmost precision, so that they would find their way to the tin. I submit all these remarks as an idea, to be followed up and elaborated in much practice, rather than as a definite piece of instruction, for the variety of circumstances is so bewildering that a fixed rule is impossible.

One of the putting problems which strike most fear into the heart of the golfer is when his line from the ball to the hole runs straight down a steep slope, and there is some[Pg 155] considerable distance for the ball to travel along a fast green. The difficulty in such a case is to preserve any control over the ball after it has left the club, and to make it stop anywhere near the hole if the green is really so fast and steep as almost to impart motion of itself. In a case of this sort I think it generally pays best to hit the ball very nearly upon the toe of the putter, at the same time making a short quick twitch or draw of the club across the ball towards the feet. Little forward motion will be imparted in this manner, but there will be a tendency to half lift the ball from the green at the beginning of its journey, and it will continue its way to the hole with a lot of drag upon it. It is obvious that this stroke, to be played properly, will need much practice in the first place and judgment afterwards, and I can do little more than state the principle upon which it should be made. But oftentimes, when the slope of the green is really considerable, and one experiences a sense of great risk and danger in using the putter at all, I strongly advise the use of the iron or mashie; indeed, I think most golfers chain themselves down too much to the idea that the putter, being the proper thing to putt with, no other club should be used on the green. There is no law to enforce the use of the putter, but even when the idea sometimes occurs to a player that it would be best to use his mashie on the green in particular circumstances, he usually rejects it as improper. On a steep incline it pays very well to use a mashie, for length in these circumstances can often be judged very accurately, and, the ball having been given its little pitch to begin with, does not then begin to roll along nearly so quickly as if the putter had been acting upon it. There are times, even when the hole is only a yard away, when it might pay best to ask for the mashie instead of the instrument which the caddie will offer.

Upon the very difficult and annoying question of stymies there are few hints that I can offer which will not suggest themselves to the player of a very little experience. The[Pg 156] fact which must be driven home is that some stymies are negotiable and others are not—not by any player or by any method. When the ball that stymies you dead is lying on the lip of the hole and half covering it, and your own is some distance away, the case is, to all intents and purposes, hopeless, but if you have only got this one stroke left for the half, you feel that an effort of some kind must be made, however hopeless it may be. The one chance—and even that is not always given—is to pass the other ball so very closely that yours will touch the rim of the hole and then, perhaps, if it is travelling slowly enough, be influenced sufficiently to tumble in. Luck must necessarily have a lot to do with the success of a stroke of this kind, and the one consolation is that, if it fails, or if you knock the other ball in—which is quite likely—things will be no worse than they appeared before you took the stroke. If, in the case of a dead and hopeless stymie of this kind, you had two strokes for the half and one for the hole, I should strongly advise you to give up all thoughts of holing out, and make quite certain of being dead the first time and getting the half. Many golfers are so carried away by their desire to snatch the hole from a desperate position of this sort, that they throw all prudence to the winds, attempt the impossible, and probably lose the hole at the finish instead of halving it. They may leave themselves another stymie, they may knock the other ball in, or they may be anything but dead after their first stroke,—indeed, it is when defying their fate in this manner that everything is likely to happen for the worst.

The common method of playing a stymie is by pitching your ball over that of your opponent, but this is not always possible. All depends on how near the other ball is to the hole, and how far the balls are apart. If the ball that stymies you is on the lip and your own is three yards away, it is obvious that you cannot pitch over it. From such a distance your own ball could not be made to clear the[Pg 157] other one and drop again in time to fall into the tin. But, when an examination of the situation makes it clear that there is really space enough to pitch over and get into the hole, take the most lofted club in your bag—either a highly lofted mashie or even a niblick—and when making the little pitch shot that is demanded, apply cut to the ball in the way I have already directed, and aim to the left-hand side of the tin. The stroke should be very short and quick, the blade of the club not passing through a space of more than nine inches or a foot. The cut will make the ball lift quickly, and, with the spin upon it, it is evident that the left-hand side of the hole is the proper one to play to. Everything depends upon the measurements of the situation as to whether you ought to pitch right into the hole or to pitch short and run in, but in any case you should pitch close up, and in a general way four or five inches would be a fair distance to ask the ball to run. When your own ball is many yards away from the hole, and the one that makes the stymie is also far from it as well as far from yours, a pitch shot seems very often to be either inadequate or impossible. Usually it will be better to aim at going very near to the stymie with the object of getting up dead, making quite certain at the same time that you do not bungle the whole thing by hitting the other ball, or else to play to the left with much cut, so that with a little luck you may circle into the hole. Evidently the latter would be a somewhat hazardous stroke to make.

There is one other way of attacking a stymie, and that is by the application of the run-through method, when the ball in front of you is on the edge of the hole and your own is very close to it—only just outside the six inches limit that makes the stymie. If the balls are much more than a foot apart, the "follow-through method" of playing stymies is almost certain to fail. This system is nothing more than the follow-through shot at billiards, and the principles upon which the strokes in the two games are made are much the[Pg 158] same. Hit your own ball very high up,—that is to say, put all the top and run on it that you can, and strike the other ball fairly in the centre and fairly hard. The object is to knock the stymie right away over the hole, and to follow through with your own and drop in. If you don't hit hard enough you will only succeed in holing your opponent's ball and earning his sarcastic thanks. And if you don't get top enough on your own ball you will not follow through, however hard you bang up against the other. This is a very useful stroke to practise, for the particular kind of stymie to which it applies occurs very frequently, and is one of the most exasperating of all.

Most of these fancy putting strokes stand a very poor chance of success on a very slow green. Cut and top and all these other niceties will not work on a dull one. It is the sharp, fiery green that comes to the rescue of the resourceful golfer in circumstances such as we have been discussing. It seems to me that golfers in considering their putts very often take too little pains to come to an accurate determination of the speed of the greens. There are a score of changing circumstances which affect that speed, but it frequently happens that only a casual glance is given to the state of the turf, and the rest of the time is spent in considering the distance and the inclines that have to be contended against. The golfer should accustom himself to making a minute survey of the condition of things. Thus, to how many players does it occur that the direction in which the mowing machine has been passed over it makes an enormous difference to the speed of the particular piece of the green that has to be putted over? All the blades of grass are bent down in the direction that the machine has taken, and their points all face that way. Therefore the ball that is being putted in the opposite direction encounters all the resistance of these points, and in the aggregate this resistance is very considerable. On the other hand, the ball that has to be putted in the same direction that the machine[Pg 159] went has an unusually smooth and slippery surface to glide over. It is very easy to see which way the machine has gone. On a newly-cut green there are stripes of different shades of green. The points of the grass give the deeper tints, and therefore the machine has been coming towards you on the dark stripes, and along them you must putt harder than on the others.

The variety of the circumstances to be taken into consideration render putting on undulating greens very attractive to the man who makes a proper and careful study of this part of the game, as every player ought to do.