CHAPTER XXIV

ARCHITECTURAL CARVING

The Necessity for Variety in Study - A Carver's View of the Study of Architecture; Inseparable from a Study of his own Craft - Importance of the Carpenter's Stimulating Influence upon the Carver - Carpenter's Imitation of Stone Construction Carried too Far.

That the study of wood-carving should be confined to the narrow field of its own performances would be the surest way to bring contempt upon an art which already offers too many temptations for the easy embodiment of puerile motives.

Such a limited range would exclude all the stimulating lessons to be derived from the many other kinds of carving and sculpture; forgetful that they are, after all, but different forms of the same art, differing only in technique and application. It would take no note of the stately sculptures of [224] Greece...the fountain-head of all that is technically and artistically perfect in expression of form...or of the splendor of imagination displayed in the ivories of Italy. Many another source of inspiring impetus would be neglected, including the greatest of all, the influence of architecture, and through it, the dignified association or the carver's art with all that is noble in the life of mankind.

The dry and uninviting aspect which a serious study of architecture presents to some minds is such that it is too often avoided as both useless and wearisome. Much of this diffidence is due to a misconception of the aims which should govern the student of decorative design in making an acquaintance with its principles. The study should not be looked upon as pertaining exclusively to the functions of an architect, nor as having only an accidental connection with particular crafts. It must be remembered that in the old days mason and carpenter were both craftsmen and architects, and the sculptor and wood-carver had an equal share in creating every feature which gives any distinction of style to the buildings that were the outcome of their united efforts.

So, instead [225] of looking upon the subject as only a study of dates for the antiquary, and rules of construction for the architect, the carver should take his own view, and regard architecture for the time being as what in some sense it really is: a very large kind of carving, which includes and gives reason for his own particular branch. The importance of the subject is proved by the experience of centuries; history showing plainly how the two arts grew in strength and beauty only when closely associated, and shared each other's fate in proportion to their estrangement.

In this place I can say but very little upon such a vast subject; all I can do is to call your attention to one or two examples of carved work combined with structural carpentry, in order that you may see for yourselves what a power of effect lies in that union, and how by contrast it enhances the value and interest of both. I do this in the hope that it may possibly lead you to a more complete study of architecture, for which there is no lack of opportunity in books and museums, but more especially in what remains of the old buildings themselves, with which a familiar and personal acquaintance will be much [226] better than a theoretical or second-hand one.

No carver with a healthy ambition can long continue to make designs and produce them in wood without feeling intensely the want of some architectural occasion for his efforts. Had he only a barge-board to carve, or the canopy of a porch, it would be such a relief to turn to its large and general treatment after a course of the panels and ornaments peculiar to domestic furniture. Look, for instance, at the carved beams of the aisle roof in Mildenhall Church given in Plate III, and think what a fund of powerful suggestion lay in the bare timbers before they were embellished by the carver with lion, dragon, and knight. Even the carpenter became inspired with a desire to make something ornamental of his own department, and has shaped and carved (literally carved) his timbers into graceful moldings. Then, again, in the roof of Sall Church, Norfolk, shown in Plate IV, you have a noble piece of carpentry which is as much the work of an artist as the carved figures and tracery which adorn it—indeed it is all just as truly carved work as those figures, being chopped out [227] of the solid oak with larger tools, ax and adze, so that one knows not which to admire most, carved angels or carved carpentry.

Plates XI and XII are details of the carvings which fill the spandrels of arch and gable in the choir stalls and screen at Winchester Cathedral. There are a great many of these panels similar in character but differing in design, some having figures, birds, or dragons worked among the foliage. They are comparatively shallow in relief, and this appears less than it really is owing to the fact that many parts of the carving dip down almost to the background, giving definite but not deep shadows. The main intention seems to have been to allow only enough shadow to secure the pattern, and then to emphasize this by means of a multitude of little illuminated masses. The leading lines run through the pattern as continuously as possible, but the surface of the leafage is divided up into numbers of little hills and hollows. The sides of these prominences catch and reflect light more readily than they produce shadow, so that it is possible to trace the pattern at a considerable distance by means of the lights alone. Unfortunately [228] for all believers in the historical evidence of ancient handicrafts, this work was overhauled some half century ago, and in parts "restored." The old work has been imitated in the new with surprising cleverness, but for that, no one who has a clear sense of the true function of the carver's art, or of the historical value of its witness to past modes of life, will thank those who carried out the "restoration," so confusing is it to be unable to distinguish at a glance the old from the new, so depressing to find such laborious efforts wasted in pleasing a childish desire for uniformity of treatment when it could only be achieved at the cost of deception, and, I may add, so irritating to find oneself for a moment deceived into accepting one of the "restored" parts as genuine old work. To add to the deception, the whole of the old woodwork, as well as the new, was smeared over with a black stain in order the better to hide the difference of color in old and new wood, thus forever destroying its soft and natural color, as well as the texture of its surface, so dear to the wood-carver.

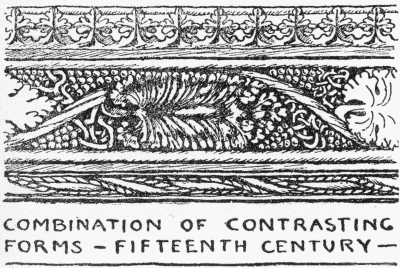

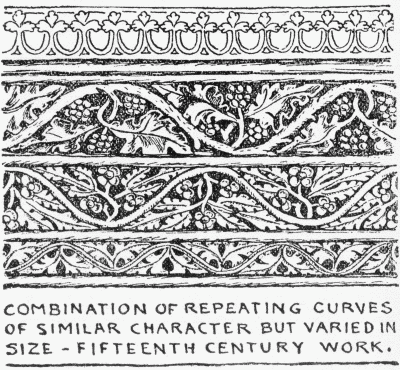

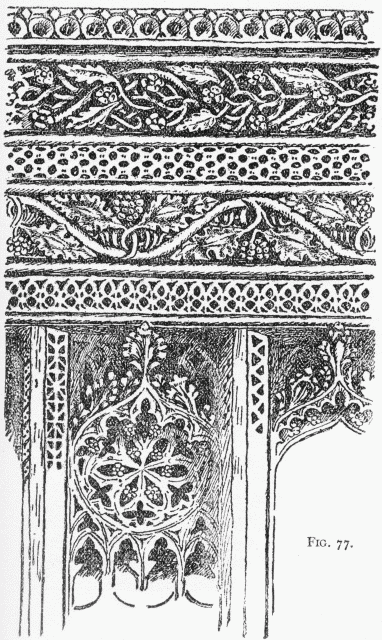

The fifteenth century in England was a period of great activity among wood-carvers, [229] and many beautiful choir-screens were added about this time to the existing churches, all in the traditional Gothic manner, as the Renaissance influence was a full century at work in other countries before its power began seriously to affect the national style. The West of England (Somerset and Devon in particular) is rich in the remains of this late Gothic carving, some details of which are shown in the accompanying illustrations, Figs. 75, 76, 77.

As a general rule the supporting carpentry of these screens bears a strong [230] resemblance to stonework; so imitative is it in treatment, that it is only by the texture of the wood and its lightness of construction that the distinction is made evident. Now a certain degree of modified imitation, where one craft models its forms of design upon those of another, using a different material, as in the case of woodwork imitations of arches, tracery, etc., is not only legitimate, but very [232] pleasing in its results. To attain this end, the carpenter need only be true to his own ideals—there is no occasion to abandon the methods of his own craft in order to copy the construction which is peculiar to another. The resources of carpentry offer an infinite field for the invention of new and characteristic forms, and these may be made all the more attractive if they show, to some extent, the influence of an associated craft, but never fail to become wearisome if essential character has been sacrificed for the sake of an ingenious imitation. The structural parts of some of these screens are composed of elaborate imitations of stone vaulting and tracery, so closely copied as to be almost deceiving, therefore they can not be taken as good examples of suggestive opportunity for the wood-carver.

The carved work, on the other hand, is marked by a strong craft character, essentially woody both in design and execution. The illustrations referred to are typical examples of this kind of work, and, although the execution can not be indicated, they at least give the disposition of parts, and some idea of the contrast obtained by [233] the use of alternate bands of ornament differing in scale, or, as in some cases, the agreeable monotony produced by a repetition of almost similar designs, varied slightly in execution.

Another prominent feature of church woodwork, which developed about this time into magnificent proportions, was the font cover and canopy. Many of these were, however, more like glorifications of the carpenter's genius for construction than examples of the carver's art, as they were composed of a multitude of tiny pinnacles and niches, the carver's work being confined to a repetition of endless crockets, tracery, and separate figures or groups. However, in Plate XIII an example is given of what they could do when working together on a more equal footing; although much mutilated, enough remains to show how the one craft gains by being associated with the other in a wholesome spirit of rivalry. [234]

|

INFORMATION ABOUT HOW TO MAKE MONEY FROM WOOD CARVING |