CHAPTER VI

CHIP CARVING

Its Savage Origin — A Clue to its only Claim to Artistic Importance — Monotony better than Variety — An Exercise in Impatience and Precision — Technical Methods.

One of the simplest, and possibly oldest, forms of wood-carving is that known as "chip" carving. This kind of work is certainly not of modern origin, as its development may be traced to a source in a common barbaric instinct for decoration in ancient inhabitants of New Zealand and other South Sea Islands. Technically, and done with modern tools, it is a form of the art which demands little skill, except in precision and patient repetition. As practiced by savage masters of woodcarving, the perfection of these two qualities elevates their work to the dignity of a real art.

It is difficult to [64] conceive the contradictory fact, that this apparently simple form of art was once the exponent of a struggling desire for refinement on the part of such fierce and warlike "brutes", and that it should, under the influence of increasingly polite society, become the all-too-easy task of esthetically minded schoolgirls. In the hands of those warrior artists, and with the crude tools at their command, mostly fashioned from sharpened fish-bones and such rude materials, it was an art which required the equivalent of many fine artistic qualities, as are understood by more cultivated nations. The marvelous dexterity and determined purpose evinced in the laborious decoration of canoe paddles, ax-handles, and other weapons, is, under such technical difficulties, such as those crude tools, really very impressive. This being so, there is no inherent reason why such a rudimentary form of the art as "chip" carving should not be practiced in a way consistent with its true nature and limitations.

As its elemental distinctions are so few, and its methods so simple, it follows that in recognizing such limitations, we shall make the most of our design. Instead, then, of trusting to a forced variety, let us seek for its strong point in an opposite [65] direction, and by the monotonous repetition of basket-like patterns, win the not-to-be-despised praise which is due to patience and perseverance. In this way only can such a restricted form of artistic expression become in the least degree interesting. The designs usually associated with the "civilized" practice of this work are, generally speaking, of the kind known as "geometric," that is to say, composed of circles and straight lines intersecting each other in complicated pattern. Now the "variety" obtained in this manner, as contrasted with the dignified monotony of the savage's method, is the note which marks a weak desire to attain great results with little effort. The "variety," as such, is wholly mechanical, the technical difficulties, with modern tools at command, are felt at a glance to be very trifling; therefore such designs are quite unsuitable to the kind of work, if human sympathies are to be excited in a reasonable way.

An important fact in connection with this kind of design is that most of these geometric patterns are, apart from their uncomfortable "variety," based on too large a scale as to detail. All the laborious carving on paddles and clubs, such as [66] may be seen in our museums, is founded upon a scale of detail in which the holes vary in size from 1/16 to something under 1/4 in. their longest way, only in special places, such as borders, etc., attaining a larger size. Such variety as the artist has permitted himself being confined to the occasional introduction of a circular form, but mostly obtained by a subtle change in the proportion of the holes, or by an alternate emphasis upon perpendicular or horizontal lines.

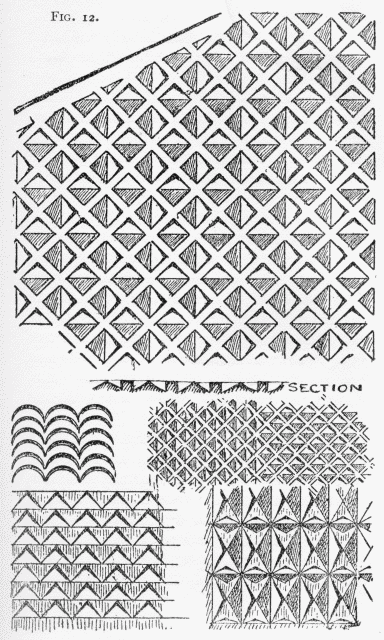

As a test of endurance, and as an experimental effort with carving tools, I set you this exercise. In Fig. 12 you will find a pattern taken from one of those South Sea carvings which we have been considering. Now, take one of the articles so often disfigured with childish and hasty efforts to cover a surface with so-called "art work," such as the side of a bellows or the surface of a bread-plate, and on it carve this pattern, repeating the same-shaped holes until you fill the entire space. By the time you have completed it you will begin to understand and appreciate one of the fundamental qualities which must go toward the making of a carver, namely, patience; and you will have produced [69] a thing which may give you pleasant surprises, in the unexpected but very natural admiration it elicits from your friends.

Having drawn the pattern on your wood, ruling the lines to measurement, and being careful to keep your lines thin and clear as drawn with a somewhat hard pencil, proceed to cut out the holes with the chisel, No. 11 on our list, 1/4 in. wide. It will serve the purpose much better than the knife usually sold for this kind of work, and will be giving you useful practise with a very necessary carving tool. The corner of the chisel will do most of the work, sloping it to suit the different angles at the bottom of the holes. Each chip should come out with a clean cut, but to insure this the downward cuts should be done first, forming the raised diagonal lines.

When you have successfully performed this piece of discipline, you may, if you care to do more of the same kind of work, carry out a design based upon the principles we have been discussing, but introducing a very moderate amount of variety by using one or more of the patterns shown in Fig. 12, all of which are [69] from the same dusky artist's designs and can not be improved upon. If you wish for more variety than these narrow limits afford, then try some other kind of carving, with perhaps leafage as its motive.

WOODCARVING BOOK - TABLE OF CONTENTS | INDEX OF TOPICS

HOBBIES

Web Page Copyright 2021 by Donovan Baldwin

Wood Carving - Chip Carving

Page Updated 3:38 PM Thursday, June 17, 2021