CHAPTER XIX

THE GROTESQUE IN CARVING

Misproportion not Essential to the Expression of Humor - The Sham Grotesque Contemptible - A True Sense of Humor Helpful to the Carver.

The dullness which comes of "all work and no play" may be said to affect the [wood]carver at times. He tires of carving leaves and ornaments: what more natural than to seek change and amusement in the invention of droll figures of men or animals? The enjoyment which we all feel in contemplating the outcome of this spirit in ancient work, leads us to the imitation of both subject and manner, hoping thereby that the same results may be obtained; but somehow the repetition is seldom attended with much success, while of original fancies of the same sort we are obliged to confess ourselves almost destitute. Who can behold the fantastic humors of Gothic carvings without being both amused and interested? Those grotesque heads with gaping mouths recall [181] the stories of childhood, peopled with goblins and gnomes. It is all so natural, and so much in keeping with the architecture which surrounds it, the carving is so rude and simple, that it seems absurd when some authority on such matters makes a statement to the effect that all such expression of humor has become forever impossible to ourselves.

This important part of the question must be left to your own meditation, to settle according to your lights; experience will probably lead you ultimately to the same opinion. Meantime, the point I wish to impress upon you is this, that until you feel

yourself secure, and something of a master of various branches of your craft, you should not attempt any subject which aims at being decidedly grotesque. There are very good and practical reasons for this; one is, that while you are studying your art, you must do nothing that may tend to obscure what faculties you have for judging proportion.

Now, as all grotesque work is based more or less on exaggeration, it forms a very dangerous kind of exercise to the beginner, therefore I should never allow a pupil of mine to so much as attempt it. Do not think [182] that I wish to discourage every effort which has not an ultra-serious aim. On the contrary, I am but taking a rather roundabout way to an admission that the humorous element has, and must have at all times, a powerful attraction for the wood-carver; and to the statement of an opinion that it should not be allowed to take a prominent place in the work of a student; moreover, that it is quite possible to find in nature a varied and unfailing source of suggestion in this respect (more, in fact, than we are ever likely to account for), and which requires no artificial exaggeration to aid its expression. Some tincture of the faculty is absolutely necessary to the carver who takes his subjects from birds or beasts, in order that he may perceive and seize the salient lines and characteristic forms, of which the key-note is often to be found in a faint touch of humor, and which, like the scent of a flower, adds charm by appealing to another sense.

The same argument applies to the treatment of the human figure. Let no student (and I may include, also, master-carver) think that a grotesque treatment will raise the smile or excite the interest [183] which is anticipated. The "grotesque" is a vehicle for grim and often terrible ideas, lightly veiled by a cloak of humorous exaggeration; a sort of Viking horse-play—it is, in fact, a language which expresses the mixed feelings of sportive contempt and real fear in about equal proportions. When these feelings are not behind the expression, it becomes a language which is in itself only contemptible.

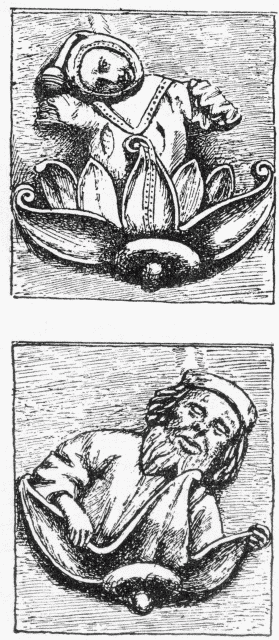

[185] If, carried away by fancy, you must find vent for its impulses, and carve images of unearthly beings, at least make them cheerful looking; one can imagine such demons and goblins as being rather nice fellows than otherwise. A grim jest that fails is generally a foolish one—at least its perpetrator neither deserves nor receives sympathy for his discomfiture. Now, I shall show you one or two examples which may make this matter a little clearer to you, if you are at all inclined to argue the position. I think, at any rate, they will prove that the expression of humor does not always depend upon exaggeration, and may exist in a work which is, one may say, almost copied from nature. Fig. 63 is an example to [186] this effect. The little jester just emerging from a flower, one of the side-pieces to a Miserere seat carving, is undoubtedly a true portrait, carved without the slightest attempt at exaggeration. The quiet humor which it evinces required only sympathy to perceive and skill to portray on the part of its carver. He had nothing to invent in the common acceptation of the word. The carving of the mendicant, which comes on the other side, is equally vivid in its truth to nature. It is so lifelike that we do not notice the humorous enjoyment of the artist in depicting the whining lips and closed eyes of the professional beggar. Observe the good manners of it all—the natural refinement of the artist who leaves his characters to make all the fun, without intrusion from himself other than to give the aid of his skill in representation. Now, subjects of this class will, in all probability, present themselves until the end of the world; but artists like this Gothic one are not so likely to be common. Great technical skill, a large fund of vitality, and many other controlling qualities are necessary to the production of such an artist; but he gives a clue to the right action, which [187] we may with safety accept, even if we can not hope to equal his performance.

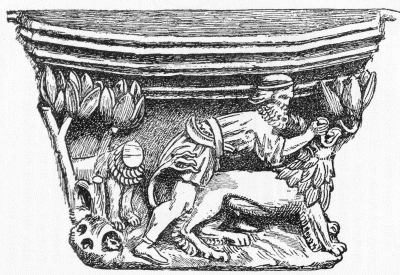

The center-piece, Fig. 64, tells a little story of Samson. It is noticeable in these medieval picture subjects, how, when a story has to be told, the details are treated in a broad and distinct fashion, as if the story could take care of itself, and only required to be stated clearly as to facts. The detached ornamental parts, on the contrary, receive a degree of careful attention not given to the picture, seemingly with the object of making their loneliness attractive.

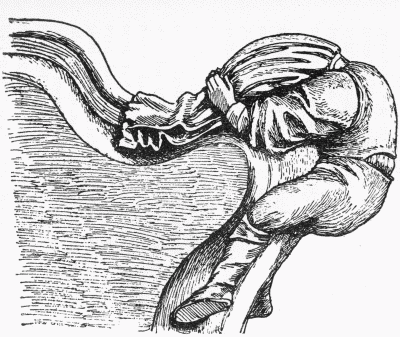

The broad-humor characteristic of the [188] companion picture of medieval life, in the little domestic scene, Fig. 65, is equally free from forced exaggeration or intentional misproportion. Scale and anatomy, to be sure, have had little consideration from the carver, but we readily forgive the inaccuracies in this respect, on account of his quick wit in devising means to an end.

Before we leave this subject, look at Plate II, in which you will see a curious use of misproportion—intentional, too, in this case—and used for quite other than humorous purposes. This is a little ornamental figure from the tomb of Henry IV, in Canterbury Cathedral. You will see that the body is out of all proportion; too small for the head which surmounts it, or too big for the feet upon which it stands. Now, what could have induced the carver to treat a dainty little lady thus? It certainly was not that he considered it an improvement upon nature, nor was it a joke on his part. It could only be done for some practical reason such as this: that the little figure does part duty as a bracket, hence, more appearance of solidity is required at the top, and less at the foot, than true proportions would [189] admit. It is all done so unostentatiously that one might look for hours at the figure without noticing the license. Not that I should advise you to imitate this [190] naive way out of a difficulty. The childlike simplicity of its treatment succeeds where conscious effort would only end in affectation.

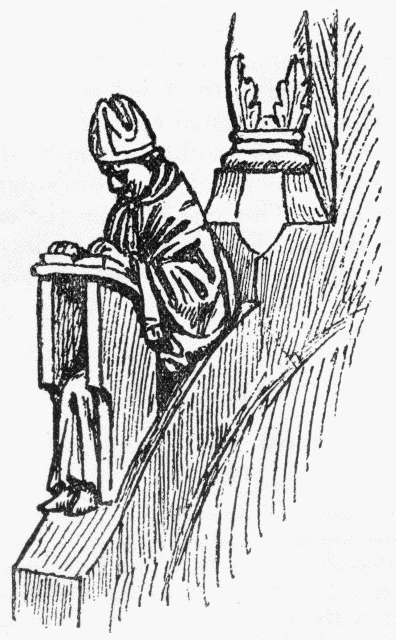

In Fig. 66 you will see another little figure doing duty in connection with a [191] stall division in the Lady Chapel at Winchester Cathedral. Its smooth roundness of form is very appropriate to the position it occupies; while its polished surface bears ample testimony that it has given no offense to the touch of the many hands which have rested upon it.

Fig. 67 shows another example of the same sort, but perched on a lower part of the division. This one is from the cathedral at Berne, each division of the stalls having a different figure, of which this is a type.

|

INFORMATION ABOUT HOW TO MAKE MONEY FROM WOOD CARVING |