CHAPTER XX

STUDIES FROM NATURE—BIRDS AND BEASTS

The Introduction of Animal Forms - Rude Vitality Better than Dull "Natural History" - "Action" - Difficulties of the Study for Town-Bred Students - The Aid of Books and Photographs - Outline Drawing and Suggestion of Main Masses - Sketch-Book Studies, Sections, and Notes - Swiss Animal Carving - The Clay Model: Its Use and Abuse.

Nothing enlivens or gives more variety of interest to wood-carving than the introduction of animal forms. They [192] make agreeable halting-places on which the eye may rest with pleasure. They are, in general, both beautiful in their shapes and associated with ideas which appeal strongly to the imagination, thus affording in masses of abstract ornament the pleasantest kind of relief by adding to it points of definite lineament and meaning.

To carve animals as they ought to be carved, one must have something more than a passing interest in their forms; there must be included also an understanding of their natures, and some acquaintance with their habits. A cattle-drover is likely to know the salient points of a bullock, a horse-breeder all those connected with a horse, and so on. We students, however, not having the advantage of such accurate and personal knowledge, must make shift in the best way we can to discover and note the points so familiar to trained eyes. To see animals in this way, and, with knowledge of their forms and habits, treat their sculptured images according to the laws of our craft, is no light task. If choice were to be made between a rude manner of carving—but which familiarity with the subject [193] invested with lively recognition of character—and a more cultured and elaborate, but lifeless study in natural history, there should be no hesitation in making choice of the former method, because animal forms, without some indication of vitality, are the dullest of all dull ornaments.

It is quite impossible to describe in words the kind of "action" which is most appropriate to sculpture, it being much more a question of treatment, and the guiding spirit of the moment, than a subject which can be formulated. As a broad and general principle which may be taken for guidance, you will always find yourself on surer ground in the attempt to indicate the capacity for energy and the suggestion of movement, than you will if your aim is the extremity of action in any direction. You may, with some justice, point to the illustration given in Fig. 65, and which appears to contradict this statement, as being an example in which violent action is the key-note. You must notice, however, that the two figures, although struggling, are for the moment still, or may be supposed so. There is enough suggestion of this pause to excuse the attitudes and save the composition [194] from restlessness - even the raised hands may be supposed to remain in the same position for a second or two. This imaginary pause, however infinitesimal, is essential to the dignity of the sculptor's art, as nothing is more irritating to the mind than being forced to recognize the contradiction between a motionless image and its suggestion of restless action. It is necessary to observe the same rule in the expression of actual repose, as some clue must be given, some completed action be suggested, in order to distinguish dormant energy from downright inertia. I should like to impress upon you the importance of making a special study of the characteristic movements of animals. You will in time become so far familiar with them that certain standards of comparison and contrast will be established in your mind as aids to memory. Thus you will be all the better able to carve with significance the measured and stately action of a horse, if you have in your mind's eye at the same time a picture of the more cumbrous and slower movements of a cow; and you will be helped in the same way when you are carving a dog, by remembering that the movements of a cat afford a [195] striking contrast, in being stealthy where the other is nervous and quick.

For the unfortunate town-bred student or artist, who has had few opportunities to study birds and beasts familiar to the country schoolboy, there is no other way but to make the best of stuffed birds, photographs, etc. Much may be done with these aids if a little personal acquaintance with their habits and associations is added like salt, to keep the second-hand knowledge sweet and wholesome.

In the absence of opportunity for study from the life, no pictures of animals can compare in their usefulness to the carver with those by Bewick. They are so completely developed in essential details, so full of character and expressive of life, that even when personal acquaintance has been made with their various qualities, a glance at one of his engravings of birds or beasts conveys new meaning, either of gesture or attitude, to what we have previously learned. Every student who wishes to make a lively representation in carving of familiar beast or bird should study [Thomas] Bewick's engravings of "Quadrupeds" and "Birds."[196]

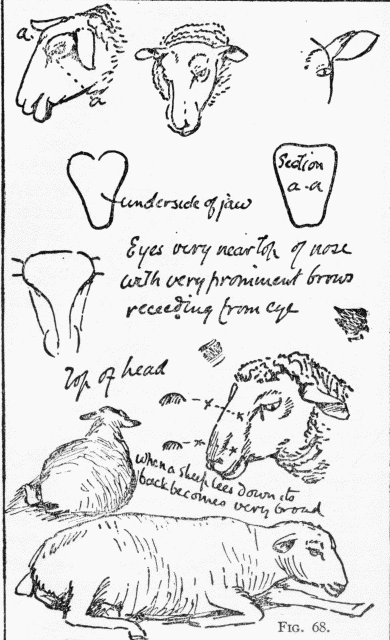

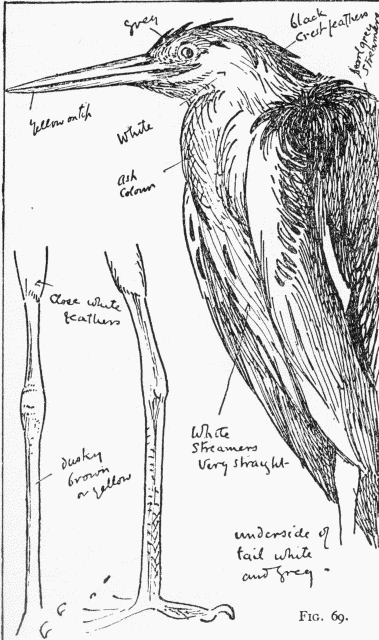

Drawings made for the purpose of study need not be elaborate: indeed, such drawings are only embarrassing to work from. The most practical plan is to make a drawing in which the main masses are given correctly, and in about the same relative position that they will occupy in the carving. I give you in Plate VII an example of this in a drawing made by Philip Webb, who, by the study of a lifetime, has amassed a valuable store of knowledge concerning animals, and acquired that extraordinary skill in their delineation and the expression of character which is only to be attained by close observation and great sympathy with the subject. The drawing in question was made for myself at the time I was carving a lion for the cover of a book (given in Plate VIII). It was made, in his good-natured way, to "help a lame dog over a stile," as I had got into difficulties with the form. This drawing is all that a carver's first diagram should be, and gives what is always the first necessity in such preliminary outlines—that is, the right relationship of the main masses, and the merest hint of what is to come in the way of detail; all of which must be studied separately, but which would be entirely useless [197] if a wrong start had been made. In Fig. 68 I give you tracings from some notes I made myself while carving the sheep in Plates V and VI. The object was to gain some definite knowledge of form by noting the relation of planes, sections of parts, projections, etc., etc. The section lines and side-notes are the most valuable part of the memoranda. In the same manner the illustration, Fig. 69, shows diagrams made from a heron, giving section lines of beak, etc.

The side-notes about the colors are valuable, as, although not translatable into carving, they do to some extent influence the manner of interpreting forms.

Photographs must not be despised, but they are only of use if read by the light of previous knowledge. For this reason you can not make too many notes of sectional structure through heads, necks, and legs, which will help to explain the mystery common to all photographs.

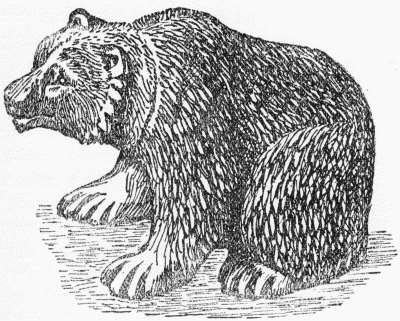

The bear shown in the frontispiece is traced from a photographic illustration which appeared in the Westminster Budget some time ago. By the merest accident it is suggestive of a subject almost ready for the carver's hand. [198]

Until tourists began to explore the beauties of Switzerland, there were no better carvers of animals than the serious but genial craftsmen of that noble country, more especially of such animals as were familiar to their eyes. This preeminence shows distinct signs of soon becoming a thing of the past in the endeavors to meet the demands created by thoughtless visitors. Still, it is possible to obtain a little of the traditional work, uninfluenced by that fatal impetus originating in modern commerce. A piece of this kind is shown in Fig. 70, bought by a friend only a year or two ago in the Grindelwald, and which, although forming part of the usual stock of such things made for tourist consumption, was picked out with judicious discrimination from a number of stupid and trivial objects which displayed neither interest of design nor other than mechanical skill of carving. This little bear, a few inches in size, is carved in a way which shows long experience of the subject, and great familiarity with the animal's ways. The tooling of the hair is done with the most extraordinary skill, and without the waste of a single touch. Now, a word or two more on studies from the life [201] before we leave this subject. I have given you examples of diagrams made for this purpose, but much may be done without any drawings, further than a preliminary map of the general masses. In the case of such an animal as the horse, which can be seen in every street, I have myself found it useful to follow them in my walks, taking mental note of such details as I happened to be engaged upon, such as its legs and joints, its head or neck; another day I would confine my attention to eyes, ears, mane, etc., always with reference to [202] the work immediately in hand, as that is the time to get the best results from life study; because the difficulties have presented themselves, and one knows exactly what to look for. Five minutes spent thus after the work has been started (provided the start has been right and involves no mistake in the general masses) is more valuable than hours of labor in making preliminary drawings.

The use of experimental models in clay or wax has, of course, its advantages, but it will be well to know just how far such an aid is valuable, and at what point its use becomes hurtful to one's work. It is a common practise in large carving shops for one man to design the figure or animal subjects in clay, while another carves them in stone or wood. Now, apart from the difference in material and the unnatural "division of labor," which we have discussed before, it is beyond question that a model of this kind has even a more paralyzing effect on the actual carver than a drawing would have. Of course, the work is more certain to reach a recognized standard, and the risk of total failure is reduced to a minimum, but there is literally nothing left for the carver [203] to invent; who, if he is a man with a turn for that kind of thing, and of a nervous temperament, must suffer untold irritation in its execution.

The good and bad results of the use of a modeled pattern attend in a modified degree even where both are done by the same hand, but for all that it is a useful and convenient way of making experiments in doubtful passages of the work. The "how far" a model is to be carried must be regulated by the amount of confidence the carver has in his own foresight, but in any case it is always well to remember the difference of treatment required in plaster, clay, and hard wood, which lead to such different results that often fresh difficulty arises in having to translate the one manner into the other. For the purpose of roughing out the general scheme, the clay, if it must be resorted to, should be used in soft masses, then a drawing in outline made from this; but all doubtful detailed work should be carved, not modeled, and for this purpose the clay should be allowed to harden until it is nearly dry.

The opinions of the well-known wood-carver, Mr. W[illiam]. Aumonier, on this subject, will be of value to you; he says with [204] regard to the best method of going to work: "A fresh piece of wood-carving executed without a model is distinctly a created work," and that much good work may come by "chopping boldly at a block without any preconceived design, but designing as you go on." But he thinks it is best to work from drawings; "rough, full-size charcoal cartoons, which give the effect wanted by their light and shade." He also says that he "strongly protests against the too frequent use of clay or plaster models, because they are often worse than useless, and not infrequently absolutely immoral in their tendency, because they absorb time and money, which ought more legitimately to be spent on the carving itself." [205]

|

INFORMATION ABOUT HOW TO MAKE MONEY FROM WOOD CARVING |