OUTDOOR SPORTS AND GAMES

BY CLAUDE H. MILLER, PH.B.

IV

CAMP COOKING

How to make the camp fire range—Bread bakers—Cooking utensils—The grub list—Simple camp recipes

Most boys, and I regret to say a few girls too, nowadays, seem to regard a knowledge of cooking as something to be ashamed of. The boy who expects to do much camping or who ever expects to take care of himself out in the woods had better get this idea out of his head just as soon as possible. Cooking in a modern kitchen has been reduced to a science, but the boy or man who can prepare a good meal with little but nature's storehouse to draw on and who can make an oven that will bake bread that is fit to eat, with the nearest range fifty miles away, has learned something that his mother or sister cannot do and something that he should be very proud of. Camp cooking is an art and to become an expert is the principal thing in woodcraft—nothing else is so important.

We often hear how good the things taste that have been cooked over the camp

fire. Perhaps a good healthy appetite has something to do with it, but it is

pretty hard even for a hungry boy to relish half-baked, soggy bread or biscuits

that are more suitable for fishing sinkers than for human food. A party without

a good cook is usually ready to break camp long before the time is up, and they

are lucky if the doctor is not called in as soon as they get home.

We often hear how good the things taste that have been cooked over the camp

fire. Perhaps a good healthy appetite has something to do with it, but it is

pretty hard even for a hungry boy to relish half-baked, soggy bread or biscuits

that are more suitable for fishing sinkers than for human food. A party without

a good cook is usually ready to break camp long before the time is up, and they

are lucky if the doctor is not called in as soon as they get home.

There is really no need for poor food in the woods. Very few woodsmen are good cooks simply because they will not learn. The camp cook always has the best fun. Every one is ready to wait on him "if he will only, please get dinner ready"

One year when I was camping at the head of Moosehead Lake in Maine, I had a guide to whom I paid three dollars a day. He cooked and I got the firewood, cleaned the fish and did the chores around camp. His cooking was so poor that the food I was forced to eat was really spoiling my trip. One day I suggested that we take turns cooking, and in place of the black muddy coffee, greasy fish and soggy biscuit, I made some Johnny cake, boiled a little rice and raisins and baked a fish for a change instead of frying it. His turn to cook never came again. He suggested himself that he would be woodchopper and scullion and let me do the cooking. I readily agreed and found that it was only half as much work as being the handy man.

The basis of camp cooking is the fire. It is the surest way to tell whether the cook knows his business or not. The beginner always starts with a fire hot enough to roast an ox and just before he begins cooking piles on more wood. Then when everything is sizzling and red-hot, including the handles of all his cooking utensils, he is ready to begin the preparation of the meal. A cloud of smoke follows him around the fire with every shift of the wind. Occasionally he will rush in through the smoke to turn the meat or stir the porridge and rush out again puffing and gasping for breath, his eyes watery and blinded and his fingers scorched almost like a fireman coming out of a burning building where he has gone to rescue some child. The chances are, if this kind of a cook takes hold of the handle of a hot frying pan, pan and contents will be dumped in a heap into the fire to further add to the smoke and blaze.

When the old hand begins to cook, he first takes out of the fire the unburned pieces and blazing sticks, leaving a bed of glowing coals to which he can easily add a little wood, if the fire gets low and a watched pot refuses to boil to his satisfaction. When the fire is simply a mass of red coals he quietly goes to cooking, and if his fire has been well made and of the right kind of wood, the embers will continue to glow and give out heat for an hour.

Of course, if the cooking consists in boiling water for some purpose, there is no particular objection to a hot fire, the fire above described is for broiling, frying and working around generally.

A type of camp fire that will burn all night

A type of camp fire that will burn all night There are all sorts of camp fireplaces. The quickest one to build and one of the best as well, is the "hunter's fire," All you need is an axe. Take two green logs about six to eight inches thick and five feet long and lay them six inches apart at one end and about fourteen inches at the other. Be sure that the logs are straight. It is a good plan to flatten the surface slightly on one side with the axe to furnish a better resting place for the pots and pans. If the logs roll or seem insecure, make a shallow trench to hold them or wedge them with flat stones. The surest way to hold them in place is to drive stakes at each end. Build your fire between the logs and build up a cob house of firewood. Split wood will burn much more quickly than round sticks. As the blazing embers fall between the logs, keep adding more wood. Do not get the fire outside of the logs. The object is to get a bed of glowing coals between them. When you are ready to begin cooking, take out the smoky, burning pieces and leave a bed of red-hot coals. If you have no axe and can find no logs, a somewhat similar fireplace can be built up of flat stones, but be sure that your stone fireplace will not topple over just at the critical time.

If you only have your jack-knife, the best fire is a "Gypsy Rig". Cut two crotched sticks, drive them into the ground and lay a crosspiece on them just as you would begin to build the leanto described in the preceding chapter, but of course not so high above the ground. The kettles and pots can be hung from the crossbar by means of pot hooks, which are pieces of wood or wire shaped like a letter "S." Even straight sticks will do with two nails driven into them. These should be of different lengths to adjust the pots at various heights above the fire, depending on whether you wish to boil something furiously or merely to let it simmer. Do not suspend the kettles by running the bar through them. This is very amateurish. With a gypsy fire, the frying pan, coffee pot and gridiron will have to be set right on the bed of coals.

An arrangement for camp fires that is better and less work than the logs is obtained by using fire irons, which are two flat pieces of iron a yard or so long resting on stones and with the fire built underneath.

The whole object of either logs or irons is to furnish a secure resting place for cooking utensils above the fire.

There are several kinds of ovens used for baking bread and roasting meat in outdoor life. The simplest way is to prop a frying pan up in front of the fire. This is not the best way but you will have to do it if you are travelling light. A reflector, when made of sheet iron or aluminum is the best camp oven. Tin is not so satisfactory because it will not reflect the heat equally. Both the top and bottom of the reflector oven are on a slope and midway between is a steel baking pan held in place by grooves. This oven can be moved about at will to regulate the amount of heat and furthermore it can be used in front of a blazing fire without waiting for a bed of coals. Such a rig can easily be made by any tinsmith. A very convenient folding reflector oven can be bought in aluminum for three or four dollars. When not used for baking, it makes an excellent dishpan.

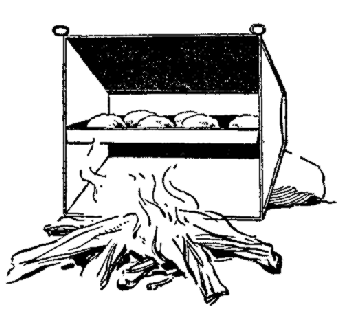

A reflector camp oven

A reflector camp oven The standard camp oven that has been used by generations of pioneers and campers is the Dutch oven. It is simply an iron pot on short legs and is provided with a heavy cover. To use it, dig a hole in the ground large enough to hold it, build a fire and fill the hole with embers. Then scoop out a place for the pot, cover it over with more embers and ashes and let the contents bake.

For the boy who wants to go to the limit in depending on his own resources, the clay oven is the nearest to real woodcraft. This is made in the side of a bank by burrowing out a hole, with a smoke outlet in the rear. A hot fire built inside will bake the clay and hold it together. To use this oven, build a fire in it and when the oven is hot, rake out the coals and put in your bread or meat on flat stones. Close the opening with another stone and keep it closed long enough to give the oven a chance. This method is not recommended to beginners who are obliged to eat what they cook, but in the hands of a real cook, will give splendid results. The reflector oven is the best for most cases if you can carry it conveniently.

The kind of a cooking equipment that we take with us on a camping trip will depend on what we can carry conveniently, how much we are willing to rough it and what our stock of provisions will be. One thing is sure—the things that we borrow from home will rarely be fit to return. In making a raid on the family kitchen, better warn the folks that they are giving us the pots and pans instead of merely lending them. Very compact cooking outfits can be bought if one cares to go to the expense. An aluminum cook kit for four people, so made that the various articles nest one into the other, can be bought for fifteen dollars. It weighs only ten pounds and takes up a space of 10 x 12 inches. Such a kit is very convenient if we move camp frequently or have to carry our outfit with us, but for the party of boys going out by team it is not worth the expense. You will need several tin pails, two iron pots, a miner's coffee pot—all in one piece including the lip—two frying pans, possibly a double boiler for oatmeal and other cooked cereals, iron spoon, large knife, vegetable knife, iron fork and broiler. A number of odds and ends will come in handy, especially tin plates to put things on. Take no crockery or glassware. It will be sure to be broken. Do not forget a can opener.

Camp fire utensils should never be soldered. Either seamless ware or riveted joints are the only safe kind. Solder is sure to melt over a hot open fire.

The personal equipment for each boy should be tin cup, knife, fork, and spoons, deep tin plate, extra plate and perhaps one extra set of everything for company if they should happen to drop in. A lot of dish washing can be avoided if we use paper or wooden plates and burn them up after the meal.

The main question is "What shall we take to eat." A list of food or as it is commonly known "the grub list" is a subject that will have to be decided by the party themselves. I will give you a list that will keep four hungry boys from staying hungry for a trip of two weeks and leave something over to bring home. If the list does not suit you exactly you can substitute or add other things. It is an excellent plan for the party to take a few home cooked things to get started on, a piece of roasted meat, a dish of baked beans, some crullers, cookies or ginger snaps. We must also consider whether we shall get any fish or game. If fishing is good, the amount of meat we take can be greatly cut down.

This list has been calculated to supply a party who are willing to eat camp fare and who do not expect to be able to buy bread, milk, eggs or butter. If you can get these things nearby, then camping is but little different from eating at home.

GRUB LIST

Ten lbs. bacon, half a ham, 4 cans corned beef, 2 lbs. cheese, 3 lbs. lard, 8 cans condensed milk, 8 lbs. hard tack, 10 packages soda crackers, 6 packages sweet crackers, 12 1/2 lbs. of wheat flour, 12 1/2 lbs. of yellow cornmeal, can baking powder, 1/2 bushel potatoes, 1 peck onions, 3 lbs. ground coffee, 1/2 lb. tea, sack salt, 7 lbs. granulated sugar, 3 packages prepared griddle cake flour, 4 packages assorted cereals, including oatmeal, 4 lbs. rice, dried fruits, canned corn, peas, beans, canned baked beans, salmon, tomatoes, sweetmeats and whatever else you like.

Be sure to take along plenty of tin boxes or tight wooden boxes to keep rain and vermin away from the food. Tell your grocer to pack the stuff for a camping trip and to put the perishable things in tight boxes as far as possible.

If you are going to move camp, have some waterproof bags for the flour. If you can carry eggs and butter, so much the better. A tin cracker box buried in the mud along some cold brook or spring makes an excellent camper's refrigerator especially if it is in the shade. Never leave the food exposed around camp. As soon as the cook is through with it let some one put it away in its proper place where the flies, ants, birds, sun, dust, and rain cannot get at it.

Always examine food before you cook it. Take nothing for granted. Once when camping the camp cook for breakfast made a huge pot of a certain brand of breakfast food. We were all tucking it away as only hungry boys can, when some one complained that caterpillars were dropping from the tree into his bowl. We shifted our seats—and ate some more, and then made the astonishing discovery that the breakfast food was full of worms. We looked at the package and found that the grocers had palmed off some stale goods on us and that the box was fairly alive. We all enjoy the recollection of it more than we did the actual experience.

It is impossible in a book of this kind to say very much about how to cook. That subject alone has filled some very large books. We can learn some things at home provided that we can duplicate the conditions in the woods. So many home recipes contain eggs, milk and butter that they are not much use when we have none of the three. There is a book in my library entitled "One Hundred Ways to Cook Eggs" but it would not do a boy much good in the woods unless he had the eggs. If you ask your mother or the cook to tell you how to raise bread or make pies and cakes, be sure that you will have the same ingredients and tools to work with that she has.

It might be well to learn a few simple things about frying and boiling, as both of these things can be done even by a beginner over the camp fire. There are a few general cooking rules that I will attempt to give you and leave the rest for you to learn from experience.

You use bacon in the woods to furnish grease in the frying pan for the things that are not fat enough themselves to furnish their own grease.

Condensed milk if thinned with water makes a good substitute for sweet milk, after you get used to it.

To make coffee, allow a tablespoonful of ground coffee to each cup of water. Better measure both things until you learn just how full of water to fill the pot to satisfy the wants of your party. Do not boil coffee furiously. The best way is not to boil it at all but that would be almost like telling a boy not to go swimming. Better let it simmer and when you are ready for it, pour in a dash of cold water to settle the grounds and see that no one shakes the pot afterward to stir up grounds—and trouble.

A teaspoonful of tea is enough for two people. This you must not boil unless you want to tan your stomach. Pour boiling water on the tea and let it steep.

Good camp bread can be made from white flour, one cup; salt, one teaspoonful; sugar, one teaspoonful and baking powder, one teaspoonful. Wet with water or better with diluted condensed milk. Pour in a greased pan and bake in the reflector oven until when you test it by sticking a wooden splinter into it, the splinter will come out clean without any dough adhering to it.

If you want to make the kind of bread that has been the standard ration for campers for hundreds of years you must eat johnny-cake or pone. It is really plain corn bread. Personally I like it better than any of the raised breads or prepared flours that are used in the woods. It should always be eaten hot and always broken by the hands. To cut it with a knife will make it heavy. The ingredients are simply one quart of yellow meal, one teaspoonful of salt and three cups—one and one-half pints—of warm water. Stir until the batter is light and bake for a short hour. Test it with the wooden splinter the same as wheat bread. It may be baked in an open fire on a piece of flat wood or by rolling up balls of it, you can even roast it in the ashes. A teaspoonful of sugar improves it somewhat and it can be converted into cake by adding raisins or huckleberries. For your butter, you will use bacon grease or gravy.

Indian meal, next to bacon, is the camper's stand-by. In addition to the johnny-cake, you can boil it up as mush and eat with syrup or condensed milk and by slicing up the cold mush, if there is any left, you can fry it next day in a spider.

The beginner at cooking always makes the mistake of thinking that to cook properly you must cook fast. The more the grease sputters or the harder the pot boils, the better. As a rule, rapid boiling of meat makes it tough. Game and fish should be put on in cold water and after the water has boiled, be set back and allowed to simmer. Do not throw away the water you boil meat in. It will make good soup—unless every one in camp has taken a hand at salting the meat, as is often the case.

All green vegetables should be crisp and firm when they are cooked. If they have been around camp for several days and have lost their freshness, first soak them in cold water. A piece of pork cooked with beans and peas will give them a richer flavour. The water that is on canned vegetables should be poured off before cooking. Canned tomatoes are an exception to this rule, however.

Save all the leftovers. If you do not know what else to do with them, make a stew or soup. You can make soup of almost anything. The Chinese use birds' nests and the Eskimos can make soup of old shoes. A very palatable soup can be made from various kinds of vegetables with a few bones or extract of beef added for body.

The length of time to cook things is the most troublesome thing to the beginner. Nearly everything will take longer than you think. Oatmeal is one of the things that every beginner is apt to burn, hence the value of the double boiler.

Rice is one of the best camp foods if well cooked. It can be used in a great variety of ways like cornmeal. But beware! There is nothing in the whole list of human food that has quite the swelling power of rice. Half a teacupful will soon swell up to fill the pot. A tablespoonful to a person will be an ample allowance and then, unless you have a good size pot to boil it in, have some one standing by ready with an extra pan to catch the surplus when it begins to swell.

There are certain general rules for cooking which may help the beginner although they are not absolute.

Mutton, beef, lamb, venison, chicken, and large birds or fish will require from ten to twenty minutes' cooking for each pound of weight. The principal value of this is to at least be sure that you need not test a five-pound chicken after it has been cooking fifteen minutes to see if it is done.

Peas, beans, potatoes, corn, onions, rice, turnips, beets, cabbage, and macaroni should, when boiled, be done in from twenty to thirty minutes. The surest test is to taste them. They will be burned in that many seconds, if you allow the water to boil off or put them in the middle of a smoky fire where they cannot be watched.

Fried things are the easiest to cook because you can tell when they are done more easily. Fried food however is always objectionable and as little of it should be eaten as possible. You are not much of a camp cook if a frying pan is your only tool.

A bottle of catsup or some pickles will often give just the right taste to things that otherwise seem to be lacking in flavour.

In frying fish, always have the pan piping hot. Test the grease by dropping in a bread crumb. It should quickly turn brown. "Piping hot" does not mean smoking or grease on fire. Dry the fish thoroughly with a towel before putting them into the pan. Then they will be crisp and flaky instead of grease-soaked. The same rule is true of potatoes. If you put the latter on brown butcher's paper when they are done, they will be greatly improved.

Nearly every camper will start to do things away from home that he would never think of doing under his own roof. One of these is to drink great quantities of strong coffee three times a day. If you find that after you turn in for the night, you are lying awake for a long time watching the stars and listening to the fish splashing in the lake or the hoot owl mournfully "too-hooing" far off in the woods, do not blame your bed or commence to wonder if you are not getting sick. Just cut out the coffee, that's all.