OUTDOOR SPORTS AND GAMES

BY CLAUDE H. MILLER, PH.B.

V

WOODCRAFT

The use of an axe and hatchet—Best woods for special purposes—What to do when you are lost—Nature's compasses

The word "woodcraft" simply means skill in anything which pertains to the woods. The boy who can read and understand nature's signboards, who knows the names of the various trees and can tell which are best adapted to certain purposes, what berries and roots are edible, the habits of game and the best way to trap or capture them, in short the boy that knows how to get along without the conveniences of civilization and is self-reliant and manly, is a student of woodcraft. No one can hope to become a master woodsman. What he learns in one section may be of little value in some other part of the country.

A guide from Maine or Canada might be comparatively helpless in Florida or

the Tropics, where the vegetation, wild animal life, and customs of the woods

are entirely different. Most of us are hopeless tenderfeet anywhere, just like

landlubbers on shipboard. The real masters of woodcraft—Indians, trappers, and

guides—are, as a rule, men who do not even know the meaning of the word "woodcraft".

A guide from Maine or Canada might be comparatively helpless in Florida or

the Tropics, where the vegetation, wild animal life, and customs of the woods

are entirely different. Most of us are hopeless tenderfeet anywhere, just like

landlubbers on shipboard. The real masters of woodcraft—Indians, trappers, and

guides—are, as a rule, men who do not even know the meaning of the word "woodcraft".

Some people think that to know woodcraft, we must take it up with a teacher, just as we might learn to play golf or tennis. It is quite different from learning a game. Most of what we learn, we shall have to teach ourselves. Of course we must profit from the experience and observation of others, but no man's opinion can take the place of the evidence of our own eyes. A naturalist once told me that chipmunks never climb trees. I have seen a chipmunk on a tree so I know that he is mistaken. As a rule the natives in any section only know enough woods-lore or natural history to meet their absolute needs. Accurate observation is, as a rule, rare among country people unless they are obliged to learn from necessity. Plenty of boys born and raised in the country are ignorant of the very simplest facts of their daily experience. They could not give you the names of a dozen local birds or wildflowers or tell you the difference between a mushroom and a toadstool to save their lives.

The wilderness traveller

The wilderness traveller On the other hand, some country boys who have kept their ears and eyes open will know more about the wild life of the woods than people who attempt to write books about it; myself, for example. I have a boy friend up in Maine who can fell a tree as big around as his body in ten minutes, and furthermore he can drop it in any direction that he wants to without leaving it hanging up in the branches of some other tree or dropping it in a soft place where the logging team cannot possibly haul it out without miring the horses. The stump will be almost as clean and flat as a saw-cut. This boy can also build a log cabin, chink up the cracks with clay and moss and furnish it with benches and tables that he has made, with no other tools than an axe and a jackknife. He can make a rope out of a grape-vine or patch a hole in his birch bark canoe with a piece of bark and a little spruce gum. He can take you out in the woods and go for miles with never a thought of getting lost, tell you the names of the different birds and their calls, what berries are good to eat, where the partridge nests or the moose feeds, and so on. If you could go around with him for a month, you would learn more real woodcraft than books could tell you in a lifetime. And this boy cannot even read or write and probably never heard the word "woodcraft." His school has been the school of hard knocks. He knows these things as a matter of course just as you know your way home from school. His father is a woodchopper and has taught him to take care of himself.

If you desire to become a good woodsman, the first and most important thing is to learn to use an axe. Patent folding hatchets are well enough in their way, but for real woodchopping an axe is the only thing. One of four pounds is about the right weight for a beginner. As it comes from the store, the edge will be far too thick and clumsy to do good work. First have it carefully ground by an expert and watch how he does it.

If I were a country boy I should be more proud of skilful axemanship than to be pitcher on the village nine. With a good axe, a good rifle, and a good knife, a man can take care of himself in the woods for days, and the axe is more important even than the rifle.

The easiest way to learn to be an axeman is to make the acquaintance of some woodchopper in your neighbourhood. But let me warn you. Never ask him to lend you his axe. You would not be friends very long if you did. You must have one of your own, and let it be like your watch or your toothbrush, your own personal property.

A cheap axe is poor economy. The brightest paint and the gaudiest labels do not always mean the best steel. Your friend the woodchopper will tell you what kind to buy in your neighbourhood. The handle should be straight-grained hickory and before buying it you will run your eye along it to see that the helve is not warped or twisted and that there are no knots or bad places in it. The hang of an axe is the way the handle or helve is fitted to the head. An expert woodchopper is rarely satisfied with the heft of an axe as it comes from the store. He prefers to hang his own. In fact, most woodchoppers prefer to make their own axe handles.

You will need a stone to keep a keen edge on the axe. No one can do good work with a dull blade, and an edge that has been nicked by chopping into the ground or hitting a stone is absolutely inexcusable.

To chop a tree, first be sure that the owner is willing to have it chopped. Then decide in which direction you wish it to fall. This will be determined by the kind of ground, closeness of other trees, and the presence of brush or undergrowth. When a tree has fallen the woodchopper's work has only begun. He must chop off the branches, cut and split the main trunk, and either make sawlogs or cordwood lengths. Hence the importance of obtaining a good lie for the tree.

Before beginning to chop the tree, cut away all the brush, vines, and undergrowth around its butt as far as you will swing the axe. This is very important as many of the accidents with an axe result from neglect of this precaution. As we swing the axe it may catch on a bush or branch over our head, which causes a glancing blow and a possible accident. Be careful not to dull the axe in cutting brush. You can often do more damage to its edge with undergrowth no thicker than one's finger than in chopping a tree a foot through. If the brush is very light, it will often be better to use your jack-knife.

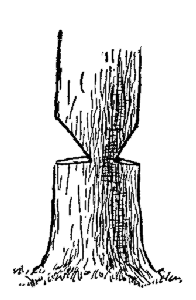

The right way to chop a tree—make two notches on opposite

sides

The right way to chop a tree—make two notches on opposite

sides In cutting a tree, first make two nicks or notches in the bark on the side to which you wish it to fall and as far apart as half the diameter of the tree. Then begin to swing the axe slowly and without trying to bury its head at every blow and prying it loose again, but with regular strokes first across the grain at the bottom and then in a slanting direction at the top. The size of the chips you make will be a measure of your degree of skill. Hold the handle rather loosely and keep your eye on the place you wish to hit and not on the axe. Do not work around the tree or girdle it but keep right at the notch you are making until it is half way through the tree. Do not shift your feet at every blow or rise up on your toes. This would tire even an old woodchopper in a short time. See that you do not set yourself too fast a pace at first. A beginner always starts with too small a notch. See to it that yours is wide enough in the start.

The wrong way—this looks like the work of a beaver

The wrong way—this looks like the work of a beaver

When you have cut about half way through, go to the other side of the tree and start another notch a little higher than the first one. A skilled man can chop either right-or left-handed but this is very difficult for a beginner. If you are naturally right-handed, the quickest way to learn left-handed wood chopping is to study your usual position and note where you naturally place your feet and hands. Then reverse all this and keep at it from the left-handed position until it becomes second nature to you and you can chop equally well from either position. This you may learn in a week or you may never learn it. It is a lot easier to write about than it is to do.

When the tree begins to creak and show signs of toppling over, give it a few sharp blows and as it falls jump sideways. Never jump or run backward. This is one way that men get killed in the woods. A falling tree will often kick backward like a shot. It will rarely go far to either side. Of course a falling tree is a source of danger anyway, so you must always be on your guard.

If you wish to cut the fallen tree into logs, for a cabin, for instance, you will often have to jump on top of it and cut between your feet. This requires skill and for that reason I place a knowledge of axemanship ahead of anything else in woodcraft except cooking. With a crosscut saw, we can make better looking logs and with less work.

Next to knowing how to chop a tree is knowing what kind of a tree to chop. Different varieties possess entirely different qualities. The amateur woodchopper will note a great difference between chopping a second growth chestnut and a tough old apple tree. We must learn that some trees, like oak, sugar maple, dogwood, ash, cherry, walnut, beech, and elm are very hard and that most of the evergreens are soft, such as spruce, pine, arbor vitae, as well as the poplars and birches. It is easy to remember that lignum vitae is one of the hardest woods and arbor vitae one of the softest. Some woods, like cedar, chestnut, white birch, ash, and white oak, are easy to split, and wild cherry, sugar maple, hemlock, and sycamore are all but unsplitable. We decide the kind of a tree to cut by the use to which it is to be put. For the bottom course of a log cabin, we place logs like cedar, chestnut, or white oak because we know that they do not rot quickly in contact with the ground. We always try to get straight logs because we know that it is all but impossible to build a log house of twisted or crooked ones.

It is a very common custom for beginners to make camp furniture, posts, and fences of white birch. This is due to the fact that the wood is easily worked and gives us very pretty effects. Birch however is not at all durable and if we expect to use our camp for more than one season we must expect to replace the birch every year or two. Rustic furniture made of cedar will last for years and is far superior to birch.

Getting lost in the woods may be a very serious thing. If you are a city boy used to signboards, street corners, and familiar buildings you may laugh at the country boy who is afraid to go to a big city because he may get lost, but he knows what being lost means at home and he fails to realize when he is in a city how easy it is to ask the nearest policeman or passer-by the way home. Most city boys will be lost in the woods within five minutes after they leave their camp or tent. If you have no confidence in yourself and if you are in a wilderness like the North woods, do not venture very far from home alone until you are more expert.

It is difficult to say when we are really lost in the woods. As long as we think we know the way home we are not lost even if we may be absolutely wrong in our opinion of the proper direction. In such a case we may soon find our mistake and get on the right track again. When we are really lost is when suddenly a haunting fear comes over us that we do not know the way home. Then we lose our heads as well as our way and often become like crazy people.

A sense of direction is a gift or instinct. It is the thing that enables a carrier pigeon that has been taken, shut up in a basket say from New York to Chicago, to make a few circles in the air when liberated and start out for home, and by this sense to fly a thousand miles without a single familiar landmark to guide him and finally land at his home loft tired and hungry.

No human being ever had this power to the same extent as a pigeon, but some people seem to keep a sense of direction and a knowledge of the points of compass in a strange place without really making an effort to do it. One thing is sure. If we are travelling in a strange country we must always keep our eyes and ears open if we expect to find our way alone. We must never trust too implicitly in any "sense of direction."

Forest travellers are always on the lookout for peculiar landmarks that they will recognize if they see them again. Oddly shaped trees, rocks, or stumps, the direction of watercourses and trails, the position of the sun, all these things will help us to find our way out of the woods when a less observing traveller who simply tries to remember the direction he has travelled may become terrified.

Rules which tell people what to do when they are lost are rarely of much use, because the act of losing our way brings with it such a confusion of mind that it would be like printing directions for terror stricken people who are drowning.

Suppose, for example, a boy goes camping for a week or two in the Adirondacks or Maine woods. If he expects to go about alone, his first step should be to become familiar with the general lay of the land, the direction of cities, towns, settlements, mountain ranges, lakes, and rivers in the section where he is going, and especially with the location of other camps, railroads, lumber camps, and so on in his immediate neighbourhood, say within a five-mile radius. It is an excellent plan to take along a sectional map which can usually be bought of the state geologist. One can by asking questions also learn many things from the natives.

Such a boy may start out from his camp, which is on the shore of a lake, for example, on an afternoon's fishing or hunting trip. If he is careful he will always consult his compass to keep in mind the general direction in which he travels. He will also tell his friends at camp where he expects to go. If he has no compass, he at least knows that the sun rises in the east and sets in the west and he can easily remember whether he has travelled toward the setting sun or away from it. Rules for telling the points of compass by the thickness of the bark or moss on trees are well enough for story books. They are not of much value to a man lost in the woods.

Suddenly, say at four o'clock, this boy decides to "turn around" and go back to camp. And then the awful feeling comes to him that he doesn't know which way to turn. The woods take on a strange and unfamiliar look. He is lost. The harder he tries to decide which way the camp lies, the worse his confusion becomes. If he would only collect his thoughts and like the Indian say "Ugh! Indian not lost, Indian here. Wigwam lost," he probably would soon get his bearings. It is one thing to lose your way and another to lose your head.

When you are lost, you are confused, and the only rule to remember is to sit down on the nearest rock or stump and wait until you get over being "rattled." Then ask yourself, "How far have I gone since I was not sure of my way?" and also, "How far am I from camp?" If you have been out three hours and have walked pretty steadily, you may have gone five miles. Unless you have travelled in a straight line and at a rapid pace, the chances are that you are not more than half that distance. But even two or three miles in strange woods is a long distance. You may at least be sure that you must not expect to find camp by rushing about here and there for ten minutes.

We have all heard how lost people will travel in circles and keep passing the same place time after time without knowing it. This is true and many explanations have been attempted. One man says that we naturally take longer steps with our right leg because it is the stronger; another thinks that our heart has something to do with it, and so on. Why we do this no one really knows, but it seems to be a fact. Therefore, before a lost person starts to hunt for camp, he should blaze a tree that he can see from any direction. Blazing simply means cutting the bark and stripping it on all four sides. If you have no hatchet a knife will do, but be sure to make a blaze that will show at some distance, not only for your own benefit but to guide a searching party that may come out to look for you. You can mark an arrow to point the direction that you are going, or if you have pencil and notebook even leave a note for your friends telling them your predicament. This may all seem unnecessary at the time but if you are really lost, nothing is unnecessary that will help you to find yourself.

As you go along give an occasional whack at a tree with your hatchet to mark the bark or bend over the twigs and underbrush in the direction of your course. The thicker the undergrowth the more blaze marks you must make. Haste is not so important as caution. You may go a number of miles and at the end be deeper in the woods than ever, but your friends who are looking for you, if they can run across one of your blazes, will soon find you.

When you are certain that you will not be able to find your way out before dark, there is not much use of going any farther. The thing to do then is to stop and prepare for passing the night in the woods while it is still daylight. Go up on the highest point of ground, build a leanto and make your camp-fire. If you have no matches, you can sometimes start a fire by striking your knife blade with a piece of flint or quartz, a hard white stone that is common nearly everywhere. The sparks should fall in some dry tinder or punk and the little fire coaxed along until you get a blaze. There are many kinds of tinder used in the woods, dried puff balls, "dotey" or rotten wood that is not damp, charred cotton cloth, dry moss, and so on. In the pitch pine country, the best kindlings after we have caught a tiny blaze are splinters taken from the heart of a decayed pine log. They are full of resin and will burn like fireworks. The Southerners call it "light-wood."

Dry birch bark also makes excellent kindlings. A universal signal of distress in the woods that is almost like the flag upside down on shipboard is to build two smoky fires a hundred yards or more apart. One fire means a camp, two fires means trouble.

Another signal is two gunshots fired quickly, a pause to count ten and then a third. Always listen after you have given this signal to see if it is answered. Give your friends time enough to get the gun loaded at camp. Always have a signal code arranged and understood by your party before you attempt to go it alone. You may never need it but if you do you will need it badly.

Sometimes we can get our bearings by climbing a tree. Another aid to determine our direction is this: Usually all the brooks and water courses near a large lake or river flow into it. If you are sure that you haven't crossed a ridge or divide, the surest way back home if camp is on a lake is to follow down the first brook or spring you come across. It will probably bring you up at the lake, sooner or later.

On a clear night you can tell the points of compass from the stars. Whether a boy or girl is a camper or not, they surely ought to know how to do this. Have some one point out to you the constellation called the "dipper." It is very conspicuous and when you have once learned to know it you will always recognize it as an old friend. The value of the dipper is this: The two stars that form the lower corners of its imaginary bowl are sometimes called the "north star pointers."

The north star or Polaris, because of its position with reference to the earth, never seems to move. If you draw an imaginary line through the two pointers up into the heavens, the first bright star you come to, which is just a little to the right of this line, is the north star. It is not very bright or conspicuous like Venus or Mars but it has pointed the north to sailors over the uncharted seas for hundreds of years. By all means make the acquaintance of Polaris.