THE COMPLETE GOLFER

By Harry Vardon

CHAPTER IXTHE CLEEK AND DRIVING MASHIE

A test of the golfer - The versatility of the cleek - Different kinds of cleeks - Points of the driving mashie - Difficulty of continued success with it - The cleek is more reliable - Ribbed faces for iron clubs - To prevent skidding - The stance for an ordinary cleek shot - The swing - Keeping control over the right shoulder - Advantages of the three-quarter cleek shot - The push shot - My favourite stroke - The stance and the swing - The way to hit the ball - Peculiar advantages of flight from the push stroke - When it should not be attempted - The advantage of short swings as against full swings with iron clubs - Playing for a low ball against the wind - A particular stance - Comparisons of the different cleek shots - General observations and recommendations - Mistakes made with the cleek.

NOTE: The function of the archaic "cleek" golf club, is now filled by the 1 and 2 irons. The "mashie", by the 3, 4, and 5 irons.

It is high time we came to consider the iron clubs that are in our bag. His play with the irons is a fine test of the golfer. It calls for extreme skill and delicacy, and the man who is surest with these implements is generally surest of his match. The fathers of golf had no clubs with metal heads, and for a long time after they came into use there was a lingering prejudice against them; but in these days there is no man so bold as to say that any long hole can always be played so well with wood all through as with a mixture of wood and iron in the proper proportions.

It may be, as we are often told, that the last improvement in iron clubs has not yet been made; but I must confess that the tools now at the disposal of the golfer come as near to my ideal of the best for their purpose as I can imagine any tools to do, and no golfer is at liberty to blame the clubmaker for his own incapacity on the links, though it may frequently happen that his choice and taste in the matter of his golfing goods[Pg 99] are at fault.

There are many varieties of every class of iron clubs, and their gradations of weight, of shape, of loft, and of all their other features, are delicate almost to the point of invisibility; but the old golfer who has an affection for a favourite club knows when another which he handles differs from it to the extent of a single point in these gradations. Some golfers have spent a lifetime in the search for a complete set of irons, each one of which was exactly its owner's ideal, and have died with their task still unaccomplished. Happy then is the player who in his early days has irons over all of which he has obtained complete mastery, and which he can rely upon to do their duty, and do it well, when the match is keen and their owner is sorely pressed by a relentless opponent.

First of these iron clubs give me the cleek [modern 1 or 2 iron], the most powerful and generally useful of them all, though one which is much abused and often called hard names. If you wish, you may drive a very long ball with a cleek, and if the spirit moves you so to do you may wind up the play at the hole by putting with it too.

But these after all are what I may call its unofficial uses, for the club has its own particular duties, and for the performance of them there is no adequate substitute. Therefore, when a golfer says, as misguided golfers sometimes do, that he cannot play with the cleek, that he gets equal or superior results with other clubs, and that therefore he has abandoned it to permanent seclusion in the locker, you may shake your head at him, for he is only deceiving himself. Like the wares of boastful advertisers, there is no other which is "just as good," and if a golfer finds that he can do no business with his cleek, the sooner he learns to do it the better will it be for his game.

And there are many different kinds of cleeks, the choice from which is to a large extent to be regulated by experiment and individual fancy. Some men fancy one type, and some another, and each of them obtains approximately the same result from his own selection, but it is natural that a driving cleek, which is specially designed for obtaining[Pg 100] length, having a fairly straight face and plenty of weight, will generally deliver the ball further than those which are more lofted and lighter. Making a broad classification, there are driving cleeks, ordinary cleeks, pitching cleeks, and cleeks with the weight in the centre. For the last-named variety I have little admiration, excellent as many people consider them to be. If the ball is hit with absolute accuracy in the centre of the club's face every time, all is well; but it is not given to many golfers to be so marvellously certain. Let the point of contact be the least degree removed from the centre of the face, where the weight is massed, and the result will usually be disquieting, for, among other things, there is in such cases a great liability for the club to turn in the hands of the player.

As an alternative to the cleek the driving mashie has achieved considerable popularity. It is undoubtedly a most useful club, and is employed for the same class of work as the cleek, and, generally speaking, may take its place. The distinctive features of the driving mashie are that it has a deeper face than that of the cleek, and that this depth increases somewhat more rapidly from the heel to the toe. By reason of this extra depth it is often a somewhat heavier club, and there is rather less loft on it than there is on the average cleek. When you merely look at a driving mashie it certainly seems as if it may be the easier club to use, but long experience will prove that this is not the case. In this respect I think the driving cleek is preferable to either the spoon or the driving mashie, particularly when straightness is an essential, as it usually is when any of these clubs is being handled. It frequently happens that the driving mashie is used to very good effect for a while after it has first been purchased; but I have noticed over and over again that when once you are off your play with it—and that time must come, as with all other clubs—it takes a long time to get back to form with it again,—so long, indeed, that the task is a most painful and depressing one. Five years ago I[Pg 101] myself had my day with the driving mashie, and I played so well with it that at that time I did not even carry a cleek. I used to drive such a long ball with this instrument, that when I took it out of my bag to play with it, my brother professionals used to say, "There's Harry with his driver again"; and I remember that when on one occasion Andrew Kirkaldy was informed that I was playing a driving mashie shot, he was indignant, and exclaimed, "Mashie! Nay, man, thon's no mashie. It's jest a driver." Then the day came when I found to my sorrow that I was off my driving mashie, and not all the most laborious practice or the fiercest determination to recover my lost form with it was rewarded with any appreciable amount of success. After a time I got back to playing it in some sort of fashion, but I was never so good with it again as to justify me in sticking to it in preference to the cleek, so since then I have practically abandoned it. This, I am led to believe, is a fairly common experience among golfers, so the moral would seem to be, that you should make the most of your good days with the driving mashie, that at the first sign of decaying power with the club another and most thorough trial should be given to the deserted cleek, and that at this crisis that club should be persevered with in preference to the tool which has failed. The driving mashie usually demands a good lie if it is to be played with any amount of success. When, in addition to the lie being cuppy, the turf is at all soft and spongy—and these two circumstances are frequently combined—the ball very often skids off the face of the club, chiefly because of its perpendicularity, instead of rising nicely from the moment of impact as it would do when carefully played by a suitable cleek. Of course if the turf is firm there is much greater chance of success with the driving mashie than if it is loose. But one finds by long experience that the cleek is the best and most reliable club for use in all these difficult circumstances. Even the driving cleeks have a certain amount of loft on their faces which enables them to get nicely under[Pg 102] the ball, so that it rises with just sufficient quickness after being struck. And there is far less skidding with the cleek.

This question of skidding calls to mind another feature of iron clubs generally, and those which are designed for power and length in particular, which has not in the past received all the consideration that it deserves. I am about to speak of the decided advantage which in my opinion accrues from the use of iron clubs with ribbed faces in preference to those which are smooth and plain. Some golfers of the sceptical sort have a notion that the ribs or other marking are merely ornamental, or, at the best, give some satisfaction to the fancy; but these are certainly not their limits. The counteraction to skidding by the ribbed face is undoubtedly very great, and there are certain circumstances in which I consider it to be quite invaluable. Suppose the ball is lying fairly low in grass. It is clear to the player that his iron club, as it approaches it, will be called upon to force its way through some of the grass, and that as it comes into contact with the ball many green blades will inevitably be crushed between the face of the club and the ball, with the result, in the case of the plain-faced club, that further progress in the matter of the follow-through will be to some extent impeded. But when the face of the club is ribbed, at the instant of contact between ball and club the grass that comes between is cut through by the ribs, and thus there is less waste of the power of the swing. The difference may be only small; but whether it is an ounce or two or merely a few pennyweights, it is the trifle of this kind that tells. And, of course, the tendency to skid is greater than ever when the grass through the green, or where the ball has to be played from, is not so short as it ought to be, and the value of the ribbed face is correspondingly increased.

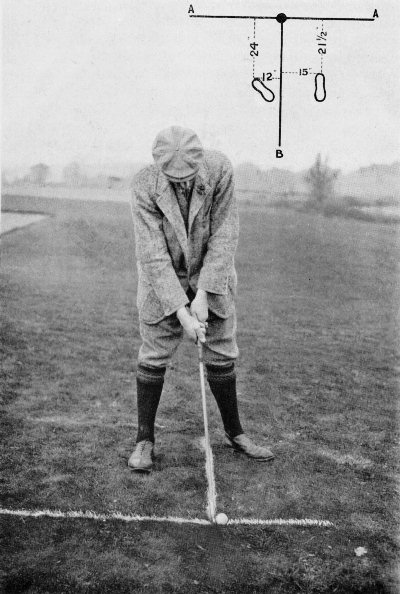

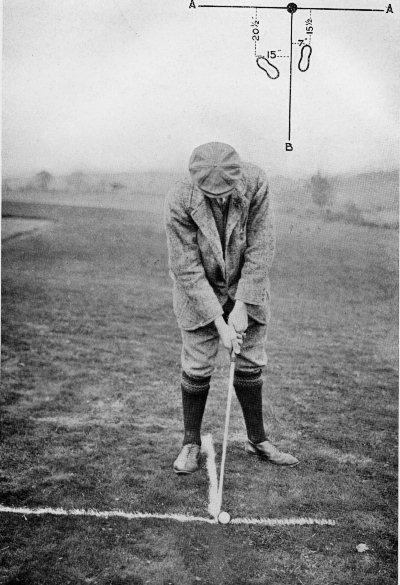

Now we may examine the peculiarities of play with the cleek, the term for the remainder of this chapter being taken to include the driving mashie. It will be found that the[Pg 103] shaft of the cleek is usually some two to four inches shorter than the driver, and this circumstance in itself is sufficient to demand a considerable modification in the stance and method of use. I now invite the reader to examine the photograph and diagram of the ordinary cleek shot (Plate XXII.), and to compare it when necessary with Plate VI., representing the stance for the drive. It will be found that the right foot is only 21½ inches from the A line as against 27½ when driving, and the left toe is only 24 inches from it as compared with 34. From this it appears that the left foot has been brought more forward into line with the right, but it is still behind it, and it is essential that it should be so, in order that the arms may be allowed a free passage through after the stroke. The feet remain about the same distance apart, but it should be noticed that the whole body has been moved forward some four inches in relation to the ball, the distances of the right and left toes from the B line being respectively 19 and 9½ inches in the case of the drive and 15 and 12 in that of the cleek shot. The stance in the case of all iron clubs should be studied with great care, for a half inch the wrong way seems to have a much greater power for evil than it does in the case of wooden clubs.

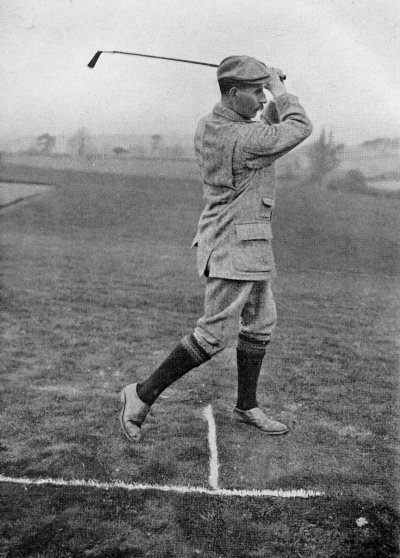

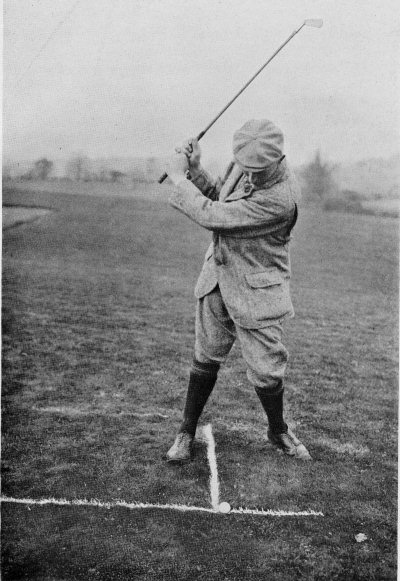

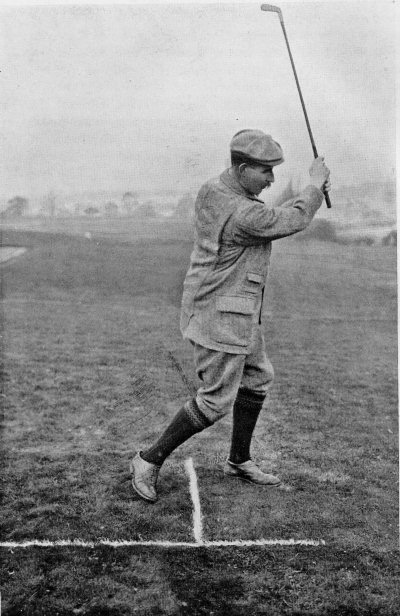

The handle of the cleek is gripped in the same manner as the driver, but perhaps a little more tightly, for, as the club comes severely into contact with the turf, one must guard against the possibility of its turning in the hands. Ground the club behind the ball exactly in the place and in the way that you intend to hit it. There is a considerable similarity between the swings with the driver and the cleek. Great care must be taken when making the backward swing that the body is not lifted upwards, as there is a tendency for it to be. When pivoting on the left toe, the body should bend slightly and turn from the waist, the head being kept perfectly still. Thus it comes about that the golfer's system appears to be working in three independent sections—first from the feet to the hips, next from the hips to the neck,[Pg 104] and then the head. The result of this combination of movements is that at the top of the swing, when everything has happened as it should do, the eyes will be looking over the top of the left shoulder—just as when at the top of driving swing. The body should not be an inch higher than when the address was made, and the right leg will now be straight and stiff. When the club is held tightly, there will be practically no danger of overswinging; but, as with the drive, the pressure with the palms of the hands may be a little relaxed at the top. The backward swing must not be so rapid that control of the club is in any degree lost, and once again the player must be warned against allowing any pause at the top. In coming down the cleek should gain its speed gradually, so that at the time of impact it is travelling at its fastest pace, and then, if the toes are right and the shoulders doing their duty, the follow-through will almost certainly be performed properly. The right shoulder must be carefully watched lest it drops too much or too quickly. The club must, as it were, be in front of it all the way. If the shoulder gets in front, a sclaffed ball is almost sure to be the result, the club coming into contact with the turf much too soon. If the stroke is finished correctly, the body will then be facing the flag.

So much, for the time being, for the full shot with the cleek. Personally, however, I do not favour a really full shot either with the cleek or any other iron club. When the limit of capability is demanded with this or most other iron clubs in the bag, it is time to consider whether a wooden instrument should not be employed. Therefore I very seldom play the full cleek shot, but limit myself to one which may be said to be slightly above the three-quarters. This is usually quite sufficient for all purposes of length, and it is easier with this limit of swing to keep the wrists and the club generally more under control. Little more can be said by way of printed instruction regarding the ordinary cleek shot, which is called for when the distance to be played falls short of a[Pg 105] full brassy, or, on the other hand, when the lie is of too cuppy a character to render the use of the brassy possible with any amount of safety.

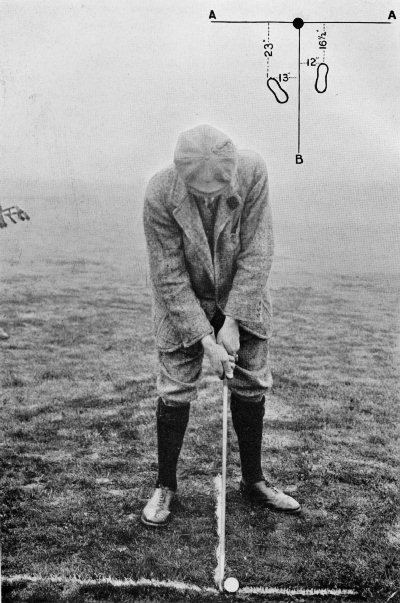

Many players, however, who are young in experience, and some who are older too, seem to imagine that the simplest stroke, as just described, is the limit of the resources of the cleek, and never give it credit for the versatility which it undoubtedly possesses. There is another shot with the cleek which is more difficult than that we have just been discussing, one which it will take many weeks of arduous practice to master, but which, in my opinion, is one of the most valuable and telling shots in golf, and that is the push which is a half shot. Of all the strokes that I like to play, this is my favourite. It is a half shot, but as a matter of fact almost as much length can be obtained with it as in any other way. It is a somewhat peculiar shot, and must be played very exactly. In the first place, either a shorter cleek (about two inches shorter, and preferably with a little more loft than the driving cleek possesses) should be used, or the other one must be gripped lower down the handle. A glance at Plate XXVI. and the diagram in the corner will show that the stance is taken much nearer to the ball than when an ordinary cleek shot was being played, that particularly the right foot is nearer, and that the body and feet have again been moved a trifle to the left. Moreover, it is recommended that in the address the hands should be held a little more forward than usual. In this half shot the club is not swung so far back, nor is the follow-through continued so far at the finish. To make a complete success of this stroke, the ball must be hit in much the same manner as when a low ball was wanted in driving against the wind. In playing an ordinary cleek shot, the turf is grazed before the ball in the usual manner; but to make this half or push shot perfectly, the sight should be directed to the centre of the ball, and the club should be brought directly on to it (exactly on the spot marked on the diagram on[Pg 106] page 170). In this way the turf should be grazed for the first time an inch or two on the far side of the ball. The diagram on this page shows the passage of the club through the ball, as it were, exactly. Then not only is the ball kept low, but certain peculiarities are imparted to its flight, which are of the utmost value when a half shot with the cleek is called for. Not only may the ball be depended upon never to rise above a certain height, but, having reached its highest point, it seems to come down very quickly, travelling but a few yards more, and having very little run on it when it reaches the turf again. When this shot is once mastered, it will be found that these are very valuable peculiarities, for a long approach shot can be gauged with splendid accuracy. The ball is sent forwards and upwards until it is almost overhanging the green, and then down it comes close to the pin. I admit that when the ball is hit in this way the shot is made rather difficult—though not so difficult as it looks—and, of course, it is not absolutely imperative that this method should be followed. Some good players make the stroke in the same way as the full shot, so far as hitting the ball is concerned, but in doing so they certainly lose the advantages I have pointed out, and stand less chance of scoring through a finely placed ball. I may remark that personally I play not only my half cleek stroke but all my cleek strokes in this way, so much am I devoted to the qualities of flight which are thereby imparted to the ball, and though I do not insist that others should do likewise in all cases, I am certainly of opinion that they are missing something when they do not learn to play the half shot in this manner. The greatest danger they have to fear is that in their too conscious efforts to keep the club clear of the ground until after the impact, they will overdo it and simply top the ball, when, of course, there will be no flight at all. I suggest that when[Pg 107] this stroke is being practised a close watch should be kept over the forearms and wrists, from which most of the work is wanted. The arms should be kept well in, and the wrists should be very tight and firm. It should be pointed out that there are some circumstances in which it is not safe to attempt to play this stroke. When the club comes to the ground after impact with the ball, very little turf should be taken. It is enough if the grass is shaved well down to the roots. But if the turf is soft and yielding, the club head will have an inevitable tendency to burrow, with the result that it would be next to impossible to follow-through properly with the stroke, and that the ball would skid off, generally to the right. The shot is therefore played to greatest advantage on a hard and fairly dry course.

Many people are inclined to ask why, instead of playing a half shot with the cleek, the iron is not taken and a full stroke made with it, which is the way that a large proportion of good golfers would employ for reaching the green from the same distance. For some reason which I cannot explain, there seems to be an enormous number of players who prefer a full shot with any club to a half shot with another, the result being the same or practically so. Why is it that they like to swing so much and waste so much power, unmindful of the fact that the shorter the swing the greater the accuracy? The principle of my own game, and that which I always impress upon others when I have an opportunity, is, "Reach the hole in the easiest way you can." The easier way is generally the surer way. When, therefore, there is a choice between a full shot with one club or a half shot with another, I invariably ask the caddie for the instrument with which to make the half shot. Hence, apart from the advantageous peculiarities of the stroke which I have pointed out, I should always play the half cleek shot in preference to the full iron, because, to my mind, it is easier and safer, and because there is less danger of the ball skidding off the club. In the same way I prefer[Pg 108] a half iron shot to a full one with the mashie. If the golfer attains any proficiency with the stroke, he will probably be very much enamoured of it, and will think it well worth the trouble of carrying a club specially for the purpose, at all events on all important occasions.

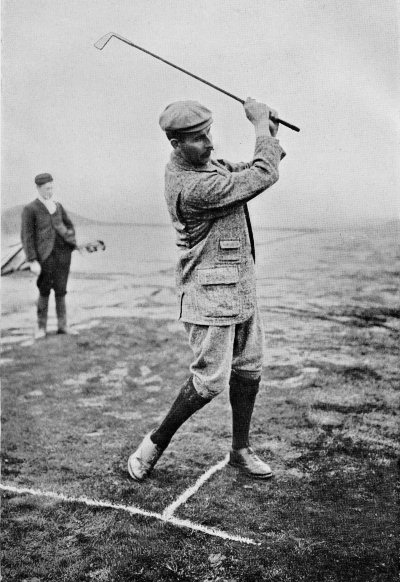

There is another variety of cleek shot which calls for separate mention. It is played when a low ball is wanted to cut its way through a head wind, and for the proper explanation of this useful stroke I have supplied a special series of photographs from which it may be studied to advantage. As will be seen from them, this stroke is, to all intents and purposes, a modified half or push stroke, the most essential difference being in the stance. The feet are a trifle nearer the ball and considerably more forward, my right heel as a matter of fact being only 2½ inches from the B line. Take a half swing, hit the ball before the turf as in the case of the push, and finish with the shaft of the club almost perpendicular, the arms and wrists being held in severe subjection throughout. The ball skims ahead low down like a swallow, and by the time it begins to rise and the wind to act upon it, it has almost reached its destination, and the wind is now welcome as a brake.

Having thus dealt with these different cleek shots separately, I think some useful instruction may be obtained from a comparison of them, noting the points of difference as they are set forth in the photographs. An examination of the pictures will at once suggest that there is much more in the stance than had been suspected. In the case of the full cleek shot it is noticeable that the stance is opener than in any of the others, and that the body is more erect. The object of this is to allow freedom of the swing without altering the position of the body during the upward movement. I mean particularly that the head is not so likely to get out of its place as it would be if the body had been more bent while the address was being made. It ought not to be, but is the case, that when pivoting on the left foot[Pg 109] during the progress of a long upward swing, there is a frequent inclination, as already pointed out, to raise the body, so that the position of the latter at the top of the swing is altogether wrong, and has to be corrected in the downward swing before the ball is reached. When, as often happens, this is done too suddenly, a sclaff is the result. Therefore an obvious recommendation is to stand at the ball with the same amount of erectness as there will be at the top of the swing. And remember that when you pivot on the left toe, the lift that there is here should not spread along to the head and shoulders, but should be absorbed, as it were, at the waist, which should bend inwards and turn round on the hips. Once the head has taken its position, it should never move again until the ball has been struck. Mind that you do not fall away from the ball when the club is about to come into contact with it. I have observed a considerable tendency in that direction on the part of many young players. I have pressed several of these points home in other places, but the success of the stroke is so bound up with a proper observation of them that I think they cannot be too frequently or too strongly insisted upon.

If we take one more glance at all the different cleek stroke photographs, we shall see that in each case the toes are turned well outwards. I find that unless they take this position the player has not the same freedom for turning upon them. In the case of full shots the weight is more evenly divided upon both feet than in the case of others. Thus, when the stance for a half or three-quarter cleek shot is taken, the weight of the body falls more on the right leg than on the left. As you have not to swing so far back, you are able to maintain this position. You could not do so if a full stroke were being taken; hence you would not then adopt it. Again, one allows the wrists and muscles less play in the case of half shots than in full ones. There is more stiffness all round. This, however, must not be taken to suggest[Pg 110] that even in the case of the full shot there is any looseness at the wrists. If there were, it would be most in evidence just when it would be most fatal, that is to say, at the moment of impact. The wrists must always be kept severely under control. It will also be noticed from the photographs, that at the top of the swings for both the full shot and the half shot the body is in much the same position, but when the low shot against the wind is being played it is pushed a little forward. I mention these details by way of suggesting how much can be discovered from a close and attentive study of these photographs only. Little things like these, when not noticed and attended to, may bother a player for many weeks; while, on the other hand, he may frequently find out from a scrutiny of the pictures and diagrams the faults which have baffled him on the links. In this connection the "How not to do it" photographs should be of particular value to the player who is in trouble with his cleek. Look at the faulty stance and address in Plate XXXII. At the first glance you can see that this is not a natural stance; the player is cramped and uncomfortable. The grip is altogether wrong. The hands are too far apart, and the right hand is too much under the shaft. The body would not hold its position during the swing, and in any case a correct swing would be impossible. Yet this photograph does not exaggerate the bad methods of some players. In Plate XXVII. we have the player in a stance which is nearly as bad as before; but it is evident that in this case the body has been lifted during the upward swing, and the left hand is rather too much on the top of the shaft.

PLATE XXXII. FAULTY PLAY WITH THE CLEEK

The stance in this case is very bad. The whole of the weight is on the left leg instead of being evenly divided. The hands are too far apart, and the right hand is far too much underneath the shaft. Moreover the player is bending too far towards his ball. He must stand up to his work. The almost certain consequence of this attitude is a foozle.

PLATE XXXIII. FAULTY PLAY WITH THE CLEEK

Some very common and very fatal defects in the swing are illustrated here. It is evident that both the body and the head have been lifted as the club has been swung up, and the whole arrangement is thus thrown out of gear. Both hands are in wrong positions (compare with XXIII) with the result that the toe of the club is pointing sideways instead of to the ground. Result—the player is likely to strike anything except the ball.

PLATE XXXIV. FAULTY PLAY WITH THE CLEEK

Here at the finish of the stroke the position of the arms is exceedingly bad. They are bent and huddled up towards the body, plainly indicating that they did not go through with the ball. There was no power in this stroke, nothing to send the ball along. Therefore length was impossible, and a foozle was quite likely. Compare with XXIV.

PLATE XXXV. FAULTY PLAY WITH THE CLEEK

The mistakes here are numerous, but less pronounced than before. The stance is not accurate, but it is not bad enough to be fatal in itself. The play is very uncomfortable with his left arm, which is in a badly cramped position. The hands are too far apart and the left wrist is too high. The result is rather doubtful. Quite possibly the ball will be pulled. Anyhow a good shot is out of the question.

PLATE XXXVI. FAULTY PLAY WITH THE CLEEK

In the case of this finish the player has fallen away from the ball instead of going forward with it as in XXIV. It is evident that the club has been drawn across the ball. Result—a slice.

Evidently it will take some time to bring the cleek completely into subjection. There is, of course, no such thing as an all-round club in golf, but the nearest to it is this one, and the man who is master of it is rarely in a serious difficulty. He can even play a respectable round with a cleek alone, and there is no form of practice less[Pg 111] wearisome, more diverting, or more eminently valuable and instructive, than that which is to be obtained on a fine afternoon by taking out the cleek and doing a round of the course with it from the tee to the hole in every case, and making use of all the different strokes that I have described in the course of this chapter.