CHAPTER X

PLAY WITH THE IRON

The average player's favourite club—Fine work for the iron—Its points—The right and the wrong time for play with it—Stance measurements—A warning concerning the address—The cause of much bad play with the iron—The swing—Half shots with the iron—The regulation of power—Features of erratic play—Forced and checked swings—Common causes of duffed strokes—Swings that are worthless.

When I mention that useful iron-headed club that goes by the simple name of iron, I am conscious that I bring forward a subject that is dear to the hearts of many golfers who have not yet come to play with certainty with all their instruments. For the iron is often the golfer's favourite club, and it has won this place of affection in his mind because it has been found in the course of long experience that it plays him fewer tricks than any of the others—that it is more dependable. This may be to some extent because with the average golfer such fine work is seldom required from the simple iron as is wanted from other clubs from time to time. The distance to be covered is always well within the capabilities of the club, or it would not be employed, and the average golfer of whom we speak, who has still a handicap of several strokes, is usually tolerably well satisfied if with it he places the ball anywhere on the green, from which point he will be enabled to hole out in the additional regulation two strokes. And the green is often enough a large place, so the iron is fortunate in its task. But it goes without saying that by those who have the skill for it, and sufficiently realise the[Pg 113] possibilities of all their tools, some of the finest work in golf may be done with the iron. When it is called for the player is within easy reach of the hole. The really long work has been accomplished, and the prime consideration now is that of accuracy. Therefore the man who feels himself able to play for the pin and not merely for the green, is he who is in the confidence of his iron and knows that there are great things to be done with it.

The fault I have to find with the iron play of most golfers is that it comes at the wrong time. I find them lunging out with all their power at full shots with their irons when they might be far better employed in effecting one of those pretty low shots made with the cleek at the half swing. It is not in the nature of things that the full iron should be as true as the half cleek, where there is such a reserve of strength, and the body, being less in a state of strain, the mind can be more concentrated on straightness and the accurate determination of length. I suspect that this full shot is so often played and the preference for the iron is established, not merely because it nearly always does its work tolerably satisfactorily, but because in the simple matter of looks there is something inviting about the iron. It has a fair amount of loft, and it is deeper in the face than the cleek, and at a casual inspection of its points it seems an easy club to play with. On the other hand, being a little nearer to the hole, the average player deserts his iron for the mashie much sooner than I care to do. Your 10-handicap man never gives a second thought as to the tool he shall use when he has arrived within a hundred yards of the hole. Is he not then approaching in deadly earnest, and has he not grown up in golf with a definite understanding that there is one thing, and one only, with which to give the true artistic finish to the play through the green? Therefore out of his bag comes the mashie, which, if it could speak, would surely protest that it is a delicate club with some fine breeding in it, and that it was never meant to do this slogging with long[Pg 114] swings that comes properly in the departments of its iron friends. I seldom use a mashie until I am within eighty yards of the hole. Up to that point I keep my iron in action. Much better, I say, is a flick with the iron than a thump with the mashie.

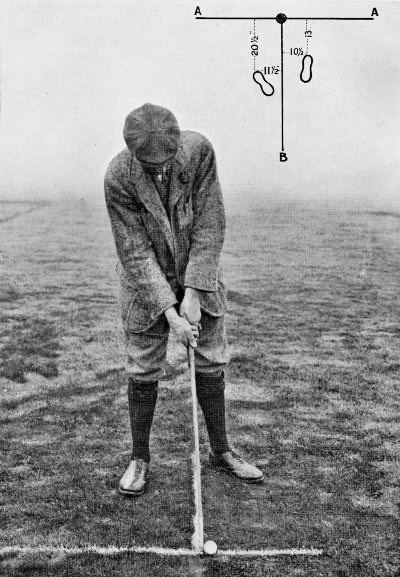

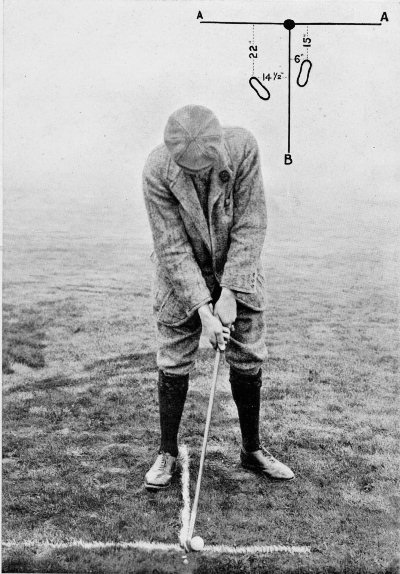

The iron that I most commonly use is nearly two inches shorter than my cleek. It follows that the stance is taken slightly nearer to the ball; but reason for moving closer to our A line is to be found in what I might describe as the more upright lie of an iron as compared with a cleek. When the lower edge of the club is laid evenly upon the level turf, the stick will usually be found to be a trifle more vertical than in the case of the cleek, and therefore for the proper preservation of the natural lie of the club the golfer must come forward to it. Consequently I find that when I have taken my stance for an iron shot (Plate XXXVII.), my right foot has come forward no less than 8½ inches from the point at which it rested when I was taking a tolerably full shot with the cleek. The left foot is 3½ inches nearer. Thus the body has been very slightly turned in the direction of the hole, and while the feet are a trifle closer together, the ball is rather nearer to the right toe than it was when being addressed by the cleek. Those are the only features of the stance, and the only one I really insist upon is the nearness to the ball. The commonest defect to be found with iron play is the failure to address the ball and play the stroke through with the sole of the club laid evenly upon the ground from toe to heel. When the man is too far from the ball, it commonly follows that the blade of the club comes down on to the turf heel first. Then something that was not bargained for happens. It may be that the ball was taken by the centre of the iron's face, and that the upward and downward swings and the follow-through were all perfection, and yet it has shot away to one side or the other with very little flight in it. And perhaps for a week or two, while this is constantly happening, the man is wondering why. When, happily, the[Pg 115] reason is at last made apparent, the man goes forward to its correction with that workmanlike thoroughness which characterises him always and everywhere, and lo! the erring ball still pursues a line which does not lead to the green. At the same time it may very likely be noticed that the slight sense of twisting which was experienced by the hands on the earlier occasion is here again. The truth is that the first fault was over-corrected, and the toe of the club, instead of the heel, has this time had the turf to itself while the ball was being removed. Obviously, when either of these faults is committed, the club head is twisted, and nothing is more impossible than to get in a perfect iron shot when these things are done. I am making much ado about what may seem after all to be an elementary fault, but a long experience of the wayward golfer has made it clear to me that it is not only a common fault, which is accountable for much defective play with the iron, but that it is often unsuspected, and lurks undiscovered and doing its daily damage for weeks or even months. The sole of the iron must pass over the turf exactly parallel with it.

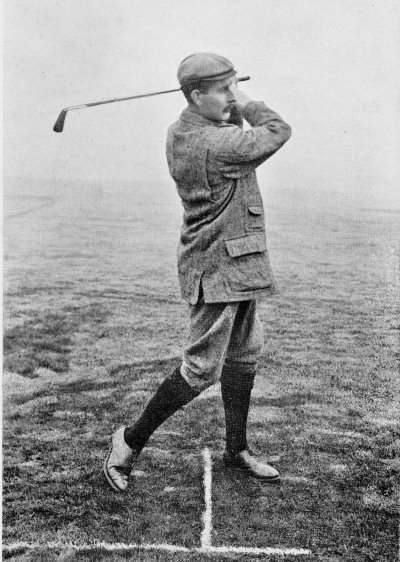

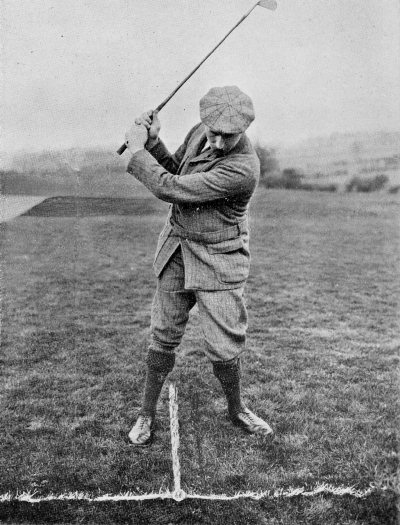

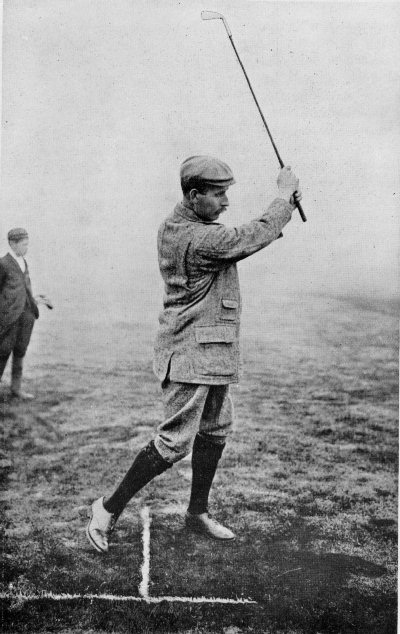

There is nothing new to say about the swing of the iron. It is the same as the swing of the cleek. For a full iron the swing is as long as for the full cleek, and for the half iron it is as long as for the half cleek, and both are made in the same way. The arms and wrists are managed similarly, and I would only offer the special advice that the player should make sure that he finishes with his hands well up, showing that the ball has been taken easily and properly, as he may see them in the photograph (Plate XXXIX.), which in itself tells a very good story of comfortable and free play with the club, which is at the same time held in full command. The whole of the series of photographs of iron shots brings out very exactly the points that I desire to illustrate, and I cannot do better than refer my readers to them.

When it is desired to play a half iron shot that will give a low ball for travelling against the wind, the same methods[Pg 116] may be pursued as when playing the corresponding shot with the cleek.

When one comes to play with the iron, and is within, say, 130 yards of the hole, the regulation of the precise amount of power to be applied to the ball becomes a matter of the first importance, and one that causes unceasing anxiety. I feel, then, that it devolves upon me to convey a solemn warning to all players of moderate experience, that the distance the ball will be despatched is governed entirely by the extent of the backward swing of the club. When a few extra yards are wanted, put an additional inch or two on to the backward swing, and so on; but never, however you may satisfy yourself with excuses that you are doing a wise and proper thing, attempt to force the pace at which the club is travelling in the downward swing, or, on the other hand, attempt to check it. I believe in the club being brought down fairly quickly in the case of all iron shots; but it should be the natural speed that comes as the result of the speed and length of the upward swing, and the gain in it should be even and continuous throughout. Try, therefore, always to swing back at the same rate, and to come on to the ball naturally and easily afterwards. Of course, in accordance with the simple laws of gravity and applied force, the farther back you swing the faster will your club be travelling when it reaches the ball, and the harder will be the hit. Therefore, if the golfer will learn by experience exactly how far back he should swing with a certain club in order to get a certain distance, and will teach himself to swing to just the right length and with always the same amount of force applied, the rest is in the hands of Nature, and can be depended upon with far more certainty than anything which the wayward hands and head of the golfer can accomplish. This is a very simple and obvious truth, but it is one of the main principles of golf, and one that is far too often neglected. How frequently do you see a player take a full swing when a half shot is all that is wanted, and even when[Pg 117] his instinct tells him that the half shot is the game. What happens? The instinct assumes the upper hand at the top of the swing, and the man with the guilty conscience deliberately puts a brake on to his club as it is coming down. He knows that he has gone too far back, and he is anxious then to reduce the speed of the club by unnatural means. But the principles of golf are not to be so lightly tampered with in this manner, and it affords the conscientious player some secret satisfaction to observe that very rarely indeed is anything of a success made of shots of this sort. A duffed stroke is the common result. In such cases the swing is of no more value than if it had not taken place at all.