THE COMPLETE GOLFER

By Harry VardonCHAPTER XIAPPROACHING WITH THE MASHIE

The great advantage of good approach play—A fascinating club—Characteristics of a good mashie—Different kinds of strokes with it—No purely wrist shot—Stance and grip—Position of the body—No pivoting on the left toe—The limit of distance—Avoid a full swing—The half iron as against the full mashie—The swing—How not to loft—On scooping the ball—Taking a divot—The running-up approach—A very valuable stroke—The club to use—A tight grip with the right hand—Peculiarities of the swing—The calculation of pitch and run—The application of cut and spin—A stroke that is sometimes necessary—Standing for a cut—Method of swinging and hitting the ball—The chip on to the green—Points of the jigger.

There is an old saying that golf matches are won on the putting greens, and it has often been established that this one, like many other old sayings, contains an element of truth, but is not entirely to be relied upon. In playing a hole, what is one's constant desire and anxiety from the tee shot to the last putt? It is to effect, somehow or other, that happy combination of excellent skill with a little luck as will result practically in the saving of a whole stroke, which will often mean the winning of the hole.

The prospect of being able to exercise this useful economy is greatest when the mashie [3 Iron] is taken in hand. The difference between a good drive and a poor one is not very often to be represented by anything like half a stroke. But the difference between a really good mashie approach stroke and a bad one is frequently at least a stroke, and I have known it to be more. Between the brilliant and the average it is one full stroke. Of course a stroke is saved and a hole very often won when a long putt is holed, but in cases of this[Pg 119] kind the proportion of luck to skill is much too great to give perfect satisfaction to the conscientious golfer, however delightful the momentary sensation may be. When a man is playing his mashie well, he is leaving himself very little to do on the putting green, so that, if occasionally he does miss a putt, he can afford to do so, having constantly been getting so near to the flag that one putt has sufficed. When the work with the mashie is indifferent or poor, the player is frequently left with long putts to negotiate, and is in a fever of anxiety until the last stroke has been made on the green. It often happens at these times that the putting also is poor, and when this is the case a sad mess is made of the score. Therefore, while I say that he is a happy and lucky man who is able constantly to save his game on the putting greens, happier by far is he who is not called upon to do so. In this way the skilled golfer generally finds the mashie the most fascinating club to play with, and there are few pleasures in the game which can equal that of laying the ball well up to the pin from a distance of many yards. One expects to get much nearer to it with this last of the irons than with the cleek or the simple iron, and the more nearly the flag is approached the greater the skill and experience of the player. Here, indeed, is a field for lifelong practice, with a telling advantage accruing from each slight improvement in play.

First a word as to the club, for there is scarcely an article in the golfer's kit which presents more scope for variety of taste and style. Drivers and brassies vary a little, cleeks and irons differ much, but mashies are more unlike each other than any of them. So much depends upon this part of the game, and so much upon the preferences and peculiarities of the player, that it is unlikely that the first mashie in which he invests will go alone with him through his experience as a golfer. To his stock there will be added other mashies, and it is probable that only after years of experiment will he come to a final determination as to which is the[Pg 120] best for him to use. In this question of the choice of mashie it is necessary that taste and style should be allowed to have their own way. However, to the hesitating golfer, or to him whose mashie play so far has been somewhat disappointing, I give with confidence the advice to use a mashie which is very fairly lofted and which is deep in the blade. I can see no use in the mashie with the narrow blade which, when (as so often happens when near the green) the ball is lying in grass which is not as short as it might be, often passes right under the ball—a loss of a stroke at the most critical moment, which is the most exasperating thing I know. Again, for a last hint I suggest that he should see that his shaft is both stiff and strong. This instrument being used generally for lighter work than the other iron clubs, and the delicacy and exactness of it being, as a rule, the chief considerations, there is a natural tendency on the part of the golfer sometimes to favour a thinner stick than usual. But it should be borne in mind that there should be no trace of "give" in the shaft, for such would be all against the accuracy that is wanted, and a man when he is playing the short approach shot wants to feel that he has a club in his hand that can be relied upon in its every fibre. Moreover, gentle as is much of its work, even the mashie at times has some very rough jobs to accomplish. So let the stick be fairly stiff.

Of mashie shots there is an infinite variety. In this stroke not only are the lie of the ball and the distance it has to be sent controlling factors in the way it has to be played, but now the nature and qualities of the green which is being approached constitute another, and one which occasions more thought and anxiety than any. Generally all mashie shots may be separated into three groups. There is what we may call the ordinary mashie shot to begin with—meaning thereby a simple lofted stroke,—there is the running-up mashie shot, and there is the special stroke which applies extra spin and cut to the ball. There are very pronounced differences between these strokes and the ways of playing[Pg 121] them. One is often told that "all mashies should be played with the wrist." I beg to differ. As I have said before, I contend that there is no such thing as a purely wrist shot in golf—except on the putting green. If anybody really made up his mind to play his mashie with his wrist and his wrist alone, he would find the blade of his club in uncomfortable proximity to his face at the finish of the stroke, and I should not like to hazard a guess as to where the ball might be. The fact of the matter is, that those who so often say that the mashie must be played with the wrist never attempt to play it in this way themselves. They are merely misled by the fact that for the majority of mashie strokes a shorter swing and less freedom of the arms are desirable than when other iron clubs are being employed. An attempt has been made to play a pure wrist shot in the "How not to do it" photograph, No. XLVIII., and I am sure nobody ever made a success of a stroke like that.

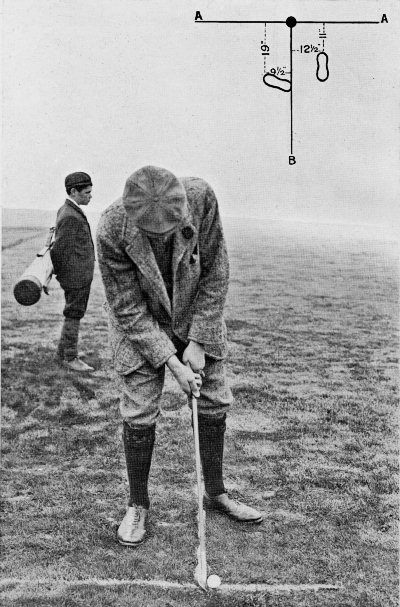

The stance for the mashie differs from that taken when an iron shot is being played, in that the feet are placed nearer to each other and nearer to the ball. Comparison between the photographs and diagrams will make the extent of these differences and the peculiarities of the stance for the mashie quite clear. The right toe is advanced until it is within 11 inches of the A line, the ball is opposite the left heel, the left foot is turned slightly more outwardly than usual. As for the grip, the only observation that it is necessary to make is, that if a very short shot is being played it is sometimes best to grasp the club low down at the bottom of the handle, but in no circumstances do I approve of the hands leaving the leather and getting on to the wood as players sometimes permit them to do. When the player is so desperately anxious to get so near to the blade with his hands, he should use a shorter club. It should also be noticed that the body is more relaxed than formerly, that there is more bend at the elbows, that the arms are not so stiff, and that there is the least suspicion, moreover, of slackness at the knees. The whole[Pg 122] attitude is arranged for ease, delicacy of touch, and extreme accuracy, whereas formerly simple straightness and power were the governing considerations. To the eye of the uninitiated, many of these photographs may seem very much alike; but a little attentive study of those showing the stances for the iron and mashie will make the essential differences very apparent. In the address the right knee is perceptibly bent, and all the weight of the body is thrown on to it. In the backward swing the right knee stiffens and the left bends in, the left foot leaning slightly over to facilitate its doing so. There is a great tendency on the part of inexperienced or uncertain players to pivot on the left toe in the most exaggerated manner even when playing a very short mashie stroke. Unless a full shot is being taken, there should not only be no pivoting with the mashie, but the left heel, throughout the stroke, should be kept either touching the ground or raised only the least distance above it. In the backward swing the right knee is stiffened and the left knee bends in towards the ball, simply in order to let the club go back properly, which it could hardly do if the original pose were retained. It is particularly requisite that, though there is so much ease elsewhere, the club in the case of these mashie shots should be held quite tightly. They are not played with the wrists alone, but with the wrists and the forearms, and a firm grip is an essential to success.

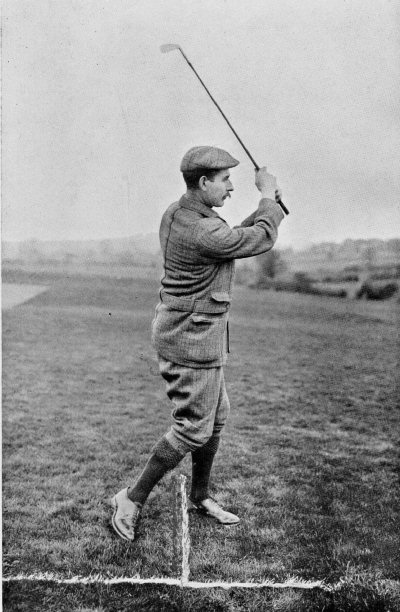

PLATE XLIV. MASHIE APPROACH (PITCH AND RUN). TOP OF THE SWING

(Distance 70 to 80 yards from the hole.)PLATE XLVI. MISTAKES WITH THE MASHIE

The hands are too far apart. Whatever method of grip is favoured at least the right thumb should be down the shaft to guide it in the case of this delicate shot. The face of the club is turned in slightly from the toe, and the face also is too straight up and is not allowed its natural angle. The toe of the club is likely to come on to the ball first, and that will cause a pull. In any case the club cannot be guided properly, and there can be no accuracy.

PLATE XLVII. MISTAKES WITH THE MASHIE

Here in this upward swing the body is being held too stiffly. It is not pivoting from the waist as it ought to do. Besides the hands being too far apart, the left one is spoiling everything. It is out of control and is trying to get above the shaft, instead of being underneath it at this stage. The result will either be a foozle or a pulled ball. The face of the mashie will not be straight at the moment of impact.

PLATE XLVIII. MISTAKES WITH THE MASHIE

This is merely a "wrist shot," such as is often recommended, and which I say cannot possibly give a good result. There is no mere wrist shot. The result of an attempt of this kind is always very doubtful. In any case, even when the ball is fairly hit, there can be no length from the stroke.

When considering the nature of the backward swing, the question arises as to how far it should be prolonged, and I have already declared myself against making long shots with the mashie. It is my strong conviction that a man is playing the best and safest golf when he attempts nothing beyond eighty yards with his mashie, using an iron or a cleek for anything longer. It is very seldom that I play my mashie at a distance of over eighty yards, and the limit of the swing that I ever give to it is a three-quarter, which is what I call an ordinary mashie stroke, and should be sufficient to do anything ever to be attempted with this[Pg 123] club. But some golfers like taking the fullest mashie stroke that they can, and, when hesitating between the use of an iron or the lofting club, they usually decide in favour of the latter. "I think I can reach it with my mashie," they always say, and so they whirl away and commit the most frightful abuse on a splendid club, which was never intended to have its capabilities strained in order to reach anything. Instead of saying that "they think they can reach it with their mashie," these golfers should try to decide that "a half iron will not carry them too far." It is easier and safer. Whenever a ball has a distance to go, I believe in keeping it fairly low down, as low as the hazards will permit, believing that in this way by constant practice it is possible to ensure much greater accuracy than in any other way. No golfer has much control over a ball that is sent up towards the sky. The mashie is meant to loft, and it is practically impossible to play a long shot with it without lofting the ball very much and exposing it to all the wind that there is about. As very little driving power has been imparted to the ball, what wind there may be has considerably more effect upon it than upon the flight of other balls played with other iron clubs.

The line of the backward swing should be much the same as that for the half shot with the cleek, but the body should be held a little more rigidly, and not be allowed to pivot quite so much from the waist as when playing with any of the other clubs which have been described. The downward swing is the same as before, and in the case of the ordinary stroke which we are speaking of, the turf should be hit immediately behind the ball. As soon as the impact has been effected, the body should be allowed to go forward with the club, care being taken that it does not start too soon and is in front.

The great anxiety of the immature player when making this stroke is to get the ball properly lofted, and in some obstinate cases it seems to take several seasons of experience to convince him completely that the club has been specially[Pg 124] made for the purpose, and, if fairly used, is quite adequate. This man cannot get rid of the idea that the player lofts the ball, or at least gives material assistance to the club in doing it. What happens? Observe this gentleman when he and his ball are on the wrong side of a hazard which is guarding the green, and notice the very deliberate way in which he goes about doing the one thing that he has been told hundreds of times by the most experienced players can only be attended by the most disastrous and costly failure. He has made up his mind that he will scoop the ball over the bunker. He will not trust to his club to do this important piece of business. So down goes the right shoulder and into the bunker goes the ball, and one more good hole has been lost. He doesn't know how it happened; he thinks the mashie must be the most difficult club in the world to play with, and he complains of his terrible luck; but by the time the approach shot to the next hole comes to be played he is at it again. There is nobody so persistent as the scooper, and the failure that attends his efforts is a fair revenge by the club for the slight that is cast upon its capabilities, for the chances are that if the stroke had been played in just the ordinary manner without any thought whatever of the bunker, and if the ground had been hit just a trifle behind the ball, the latter would have been dropped easily and comfortably upon the green. Some golfers also seem to imagine that they have done all that they could reasonably be expected to do when they have taken a divot, and even if the shot has proved a failure they derive some comfort from the divot they have taken, the said divot usually being a huge slab of turf, the removal of which makes a gaping wound in the links. But there is nothing to be proud of in this achievement, for it does not by any means imply that the stroke has been properly made. To hit the ball correctly when making an approach with the mashie, it is necessary to take a little—just a very little—turf. This is so, because the ball will not fly and rise properly as the club desires to make it do,[Pg 125] unless it is taken in the exact middle of the club, which has a deeper face than others. I mean middle, not only as regards the distance from heel to toe, but between the top edge of the blade and the sole. A moment's consideration will make it clear that if the stroke were to be made quite cleanly, that is to say, if the club merely grazed the ground without going into it, the ball would inevitably be taken by the lower part of the blade near to the sole and much below the centre where the impact ought to be. Therefore it is apparent that, in order to take it from the centre, the blade must be forced underneath, and if the swing is made in the manner directed and the turf is taken just the least distance behind the ball—which, of course, means keeping the eye just so much more to the right than usual—all that is necessary will be easily accomplished. Apart from the loft, I think a little more accuracy is ensured by the removal of that inch or two of turf.

Now there is that most valuable stroke, the running-up approach, to consider. When skilfully performed, it is often most wonderfully and delightfully effective. It is used chiefly for short approaches when the ground outside the putting green is fairly good and there is either no hazard at all to be surmounted, or one that is so very low or sunken as not to cause any serious inconvenience. When the running-up shot is played in these circumstances by the man who knows how to play it, he can generally depend on getting much nearer to the hole than if he were obliged to play with a pitch alone. It is properly classified as a mashie shot, but there are golfers who do it with an iron. Others like a straight-faced mashie for the purpose; and a third section have a preference for the ordinary mashie, and play for a pitch and run. These are details of fancy in which I cannot properly interfere. The stance for the stroke differs from that for an ordinary mashie shot in that the feet and body are further in front, the right toe, for instance, being fully six inches nearer to the B line (see Plate XLIX.). The club may be[Pg 126] gripped lower down the handle. Moreover, it should be held forward, slightly in front of the head. The swing back should be very straight, and should not be carried nearly so far as in playing an ordinary mashie stroke, for in this case the ball requires very little propulsion. This is one of the few shots in golf in which the right hand is called upon to do most of the work, and that it may be encouraged to do so the hold with the left hand should be slightly relaxed. With the right hand then fastening tightly to the handle, it comes about that the toe of the club at the time of the impact is slightly in front of the heel, and this combination of causes tends to give the necessary run to the ball when it takes the ground. The work of the right hand in the case of this stroke is delicate and exact, and it must be very carefully timed, for if it is done too suddenly or too soon the result is likely to be a foundered ball. The club having been taken so straight out in the backward swing, the natural tendency will be to draw it very slightly across the ball when contact is made, and the blade, then progressing towards the left foot, should to finish be taken a few inches further round towards the back than in the case of an ordinary mashie shot. One cannot very well compare the two in words, however, for the finishes are altogether different, as an examination of the illustration of the finish of the running-up stroke will show. In this case the swing stops when the shaft of the club is pointing a little to the left of the direction of the ball that is speeding onwards, the blade being on a level with the hands. It will be observed that at the finish the right hand is well over on the handle. This is the kind of stroke that the practised and skilful golfer loves most, for few others afford him such a test of calculation and judgment. It will not do to make the stroke haphazard. Before the blade of the club is moved for the upward swing, a very clear understanding should have been formed as to the amount of pitch that is to be given to the ball and the amount of run. They must be in exactly the proper proportion[Pg 127] to suit the circumstances, which will vary almost every time the stroke is made. Nearly everything depends on the state of the land that is to be traversed. The fact of the matter is, that this shot is really a combination of lofting and putting with many more uncertain quantities to be dealt with than when one is really putting on the green. When one has decided where the pitch must be, the utmost pains should be taken to pitch there exactly, which, as the distance will usually be trifling, ought not to be a difficult matter. An error of even a foot in a shot of this kind is sometimes a serious matter. When properly done it is an exceedingly pretty shot, and one which brings great peace to the soul of the man who has done it.

And now we come to that exquisite stroke, the approach, to which much cut and spin have been applied for a specific purpose. It is a shot which should only be played when circumstances render it absolutely necessary. There are times when it is the only one which will afford the golfer a good chance of coming well through a trying ordeal. When we play it we want the ball to stop dead almost as soon as it reaches the turf at the end of the pitch. If there is a tolerably high bunker guarding the green, and the flag is most awkwardly situated just at the other side, it is the only shot that can be played. A stroke that would loft the ball over the bunker in the ordinary manner would carry it far beyond the hole—too far to make the subsequent putting anything but a most difficult matter. Or, on the other hand, leaving out of the question the hole which is hiding just on the other side of the hazard protecting the green, it often happens in the summer-time, when greens are hard and fiery, that it is absolutely impossible to make a ball which has been pitched on to them in the ordinary manner stay there. Away it goes bouncing far off on to the other side, and another approach shot has to be played, often by reason of a hazard having been found, more difficult than the first. If there must be a pitch, then the thing to do is to try to apply a[Pg 128] brake to the ball when it comes down, and we can only do this by cutting it. There are greens which at most seasons of the year demand that the ball reaching them shall be cut for a dead drop, such as the green laid at a steep angle when the golfer has to approach it from the elevated side. A little cut is a comparatively easy thing to accomplish, but when the brake is really wanted it is usually a most pronounced cut, that will bring the ball up dead or nearly so, that is called for, and this is a most difficult stroke. I regard the ordinary mashie as the best club with which to make it, but there are some good golfers who like the niblick for this task, and it is undoubtedly productive of good results. However, I will suppose that it is to be attempted with the mashie.

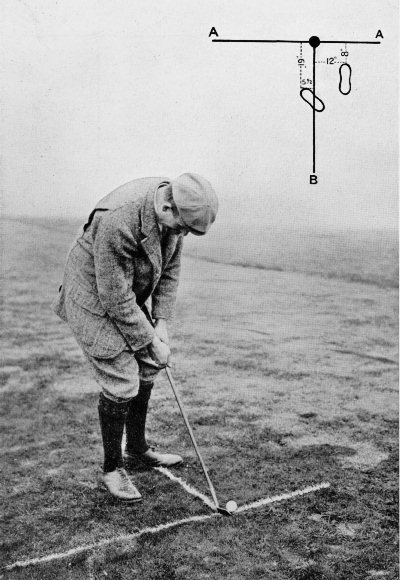

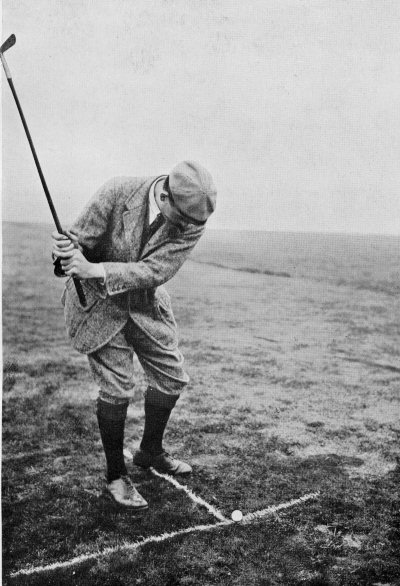

The stance is quite different from that which was adopted when the running-up shot was being played. Now the man comes more behind the ball, and the right foot goes forward until the toe is within 8 inches of the A line, while the instep of the left foot is right across B. The feet also are rather closer together. An examination of Plate L. will give an exact idea of the peculiarities of the stance for this stroke. Grip the club very low down on the handle, but see that the right hand does not get off the leather. This time, in the upward swing let the blade of the mashie go well outside the natural line for an ordinary swing, that is to say, as far away from the body in the direction of the A line as is felt to be comfortable and convenient. While this is being done, the left elbow should be held more stiffly and kept more severely under control than the right. At the top of the swing—which, as will be seen from the picture of it (Plate LI.), is only a short half swing, and considerably shorter than that for an ordinary mashie shot—neither arm is at full length, the right being well bent and the left slightly. When this upward swing has been made correctly, the blade of the mashie naturally comes across the ball at the time of impact, and in this way a certain amount of cut is applied. But this is not the limit[Pg 129] of the possibilities of cutting, as many golfers seem to imagine, nor is it sufficient to meet some of the extreme cases which occasionally present themselves. To do our utmost in this direction we must decide that extremely little turf must be taken, for it is obvious that unless the bare blade gets to work on the ball it cannot do all that it is capable of doing. The metal must go right underneath the ball, just skimming the grass in the process, and scarcely removing any of the turf. It is also most important that at the instant when ball and club come into contact the blade should be drawn quickly towards the left foot. To do this properly requires not only much dexterity but most accurate timing, and first attempts are likely to be very clumsy and disappointing. But many of the difficulties will disappear with practice, and when at last some kind of proficiency has been obtained, it will be found that the ball answers in the most obedient manner to the call that is made upon it. It will come down so dead upon the green that it may be pitched up into the air until it is almost directly over the spot at which it is desired to place it. In playing this stroke a great deal depends on the mastery which the golfer obtains over his forearms and wrists. At the moment of impact the arms should be nearly full length and stiff, and the wrists as stiff as it is possible to make them. I said that the drawing of the blade towards the left foot would have to be done quickly, because obviously there is very little time to lose; but it must be done smoothly and evenly, without a jerk, which would upset the whole swing, and if it is begun the smallest fraction of a second too soon the ball will be taken by the toe of the club, and the consequences will not be satisfactory. I have returned to make this the last word about the cut because it is the essence of the stroke, and it calls for what a young player may well regard as an almost hopeless nicety of perfection.

There is another little approach shot which is usually called the chip on to the green, but which is really nothing but the pitch and run on a very small scale. It is used when[Pg 130] the ball has only just failed to reach the green, or has gone beyond it, and is lying in the rougher grass only a very few yards from the edge of it. It often happens in cases of this sort that the putter may be ventured upon, but when that is too risky a little pitch is given to the ball and it is allowed to run the last three or four yards to the hole. An ordinary iron will often be found the most useful club for the purpose.

Latterly a new kind of club has become fashionable in some quarters for approaching. They call it the jigger, and, having a longer blade than the ordinary mashie, its users argue that it is easier to play with. That may be true to a certain extent when the ball is lying nicely, but we are not always favoured with this good fortune, and I have no hesitation in saying that for inferior or cuppy lies the jigger is a very ineffectual instrument. The long head cannot get into the cups, and the accuracy that is always called for in approaching is made impossible. If a jigger must be carried in the bag, it should be merely as an auxiliary to the ordinary mashie.

Such are the shots with the mashie, and glad is the man who has mastered all of them, for he is then a golfer of great pretensions, who is to be feared by any opponent at any time or place.