CHAPTER XXI

FORESHORTENING AS APPLIED TO WORK IN RELIEF

Intelligible Background Outline Better than Confused Foreshortening - Superposition of Masses.

I have spoken of the necessity for careful balance between the outlines of subject and background: that both should be agreeable in shape. This becomes complicated and more difficult to arrange when we admit into our design anything resembling what painters call foreshortening, and the awkwardness is felt even in the placing of such a small thing as an apple-leaf, which may be treated in such a way that the intention of the drawing is entirely lost in the confusion which arises between the inferred and the actual projection.

http://informationclickdepot.com/hobby/woodcarving/collotype-plates.html#plate8In designing such subjects it will be good to bear in mind as a guiding principle that no matter what excuse there may be in the nature of the inferred position of the leaf or limb, the outline against the background must be at once agreeable and explanatory.

Every kind of work in relief develops a species of compromise in the expression of form, lying somewhere between the representation of an object on a perfectly flat ground, as in a painting, and the complete realization of the same form, copied from nature in some solid material, without any background whatever. In proportion to the amount of actual projection from the background, of course the necessity diminishes for that kind of foreshortening which is obtained by delineation. It might be inferred, therefore, that in very low relief—which is more nearly akin to the nature of a picture—more liberty may be taken in this direction. It is not so, however, for where actual depth or projection exists, as in carving, be it only so much as the depth of a line, it makes foreshortening well-nigh impossible, except to a very limited extent.

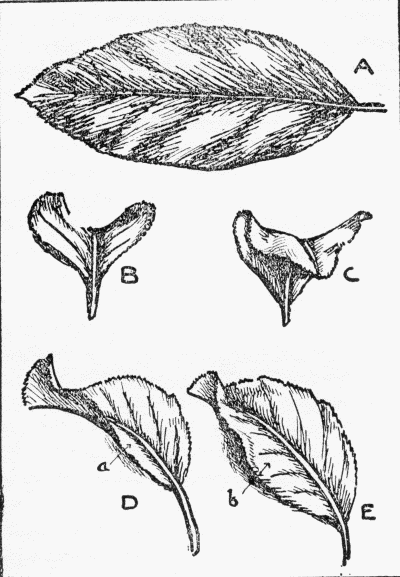

There must be, of course, some appearance of this quality, so a certain conventional standard has been set up, beyond which one only ventures at one's own risk. Thus, care is taken that every object composing the subject lies with its longest lines parallel to the background. In this way the least possible violence is done to the imagination in completing the picture. As an example, no single leaf should be represented in [208] relief as turning or coming forward more than it would do if plucked from the tree and laid loosely down upon a sheet of paper. A, Fig. 71, is an outline of an apple-leaf pressed out flat. B is an attempt to present it in violent foreshortening, showing its back to the spectator, while its point is supposed to be buried in the background. C is the same leaf turned the other way, and supposed to be projecting forward; both are exceedingly awkward and unintelligible as mere outlines, and if expressed in relief would not be any more convincing as portraits of the thing intended—rather less so, in fact, than the diagram, which has no projection to interfere with the drawing. So we must turn our leaf until it presents its long side more or less to the spectator, as in D; but even here part of the edge is so thin at a that it will be better to turn it a little farther, as in E, showing more of its surface, as at b.

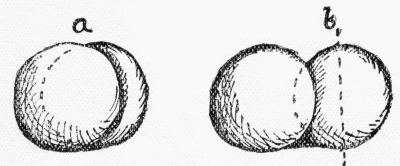

Again, if we take as another example two apples, one partly covering the other, as in a, Fig. 72, where one apple is supposed to be behind the other, and so implies distance. There is no means of expressing this distance in carving. [209]

Lowering the surface of the hindmost apple would merely throw out the balance of masses without giving a satisfactory explanation of its position, while to cut a deep groove between the two would be an equally unsightly expedient. The difficulty should, whenever it is possible, be avoided by partially separating the two forms, as in b, where the center of the hindmost apple clears the outline of the other; thus making it possible to get a division without awkwardness.

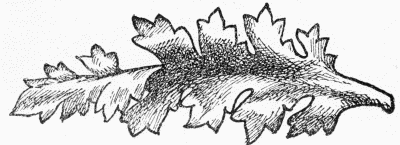

A good expedient, where leaf or scroll forms are to be carved, and when very truthful drawing is necessary to explain their convolutions, is that adopted by Professor Lethaby at the Royal College of Art. It consists in cutting the leaf out of a piece of stiffish paper, and with a knife or pen-handle curling it into the required [210] form. The main lines will thus be seen in true relation to one another, and all the distortion avoided which arises from disconnection of parts; not only that, but it is a useful aid to the invention, as much variety can be hinted at by a skilful manipulation in curling its lobes.

Fig. 73 was drawn from a paper model of this kind.

Of course, it is quite without the necessary veins or minor articulations, but is useful as a suggestion of main lines. With regard to subjects containing figures of men or animals, the same principle governs the placing of the whole body in the first instance, then of the different members, so that heads, arms, and legs take up a position as nearly as may be with a piece of background all to themselves. Thus, no two bodies should be super-imposed [211] if it can be in any way avoided. (I am speaking now of moderate and low relief, although even in high relief the best masters have always respected the principle.) The temptation to imitate effects of foreshortening for its own sake is not without some excuse, as it is quite possible to make presentable pictures in this way.

A horse, for instance, may be carved in low relief, presenting either its head or hindquarters to the spectator, and yet not look absolutely absurd. Again, a front face may be carved in the same way, notwithstanding the difficulty presented by the projection of the nose.

Neither of these experiments can ever be said to prove entirely successful.

It is not so much that they are either difficult or impossible, as that a more suitable method, one more natural to the technique of the carver, is being neglected, and its many good qualities sacrificed for sake of an effect which can never be fully realized in sculpture. To so dispose the various masses, great and small, that they fall easily into groups, each having some relation to, and share of the background, is a true carver's artifice. A skilful use of this arrangement makes it quite unnecessary to encroach upon the [212] domain of another art in the imitation of an effect which may be successfully rendered with the pencil, but only so to a very limited extent with the carving tools.

You have all seen the actors, when called before the curtain at the close of the play, how they pass before it one by one, and perhaps joining hands make their bows in line, to all appearance, on a very narrow platform. The curtain is your background, while the footlights may stand for the surface of your wood. In illustration of this principle, let me call your attention to the arrangement of the animals in Plate VI, where economy of space, and a desire to display each detail to advantage, are the leading motives. I give it as the readiest example to hand, and because it fairly illustrates the principle in question. You must excuse the apparent vanity in making choice of one of my own works to exemplify a canon of art. The sheep at the top is supposed to be scampering over rocks; the ram below may be any distance from the sheep that you choose to imagine—the only indication of relative position is separation, by means of a ridge that may pass for a rock. The head of the ram is somewhat foreshortened, but there was enough thickness [213] of wood contained in the big mass of the body to allow of this being done in the smaller mass of the head, without leaving too much to be supposed. The heads of the sheep in the fold have been as closely packed as was consistent with showing as much of each as possible, as it was considered better to give the whole head and no body than to show only a part of both: most of the bodies, therefore, are supposed to be hidden behind the wall, only one showing in part.

It is a general axiom of the craft, that every mass (be it body or leaf) must be made as complete in itself as the circumstances will allow; but, if partly hidden, the concealment should be wilful, and without ambiguity. Thus, a dog's head may be rightly carved as being partly hidden in a bucket, but ought not to be covered by another head if it is possible to avoid it.

|