THE COMPLETE GOLFER

By Harry Vardon

CHAPTER VIDRIVING—THE SWING OF THE CLUB

"Slow back"—The line of the club head in the upward swing—The golfer's head must be kept rigid—The action of the wrists—Position at the top of the swing—Movements of the arms—Pivoting of the body—No swaying—Action of the feet and legs—Speed of the club during the swing—The moment of impact—More about the wrists—No pure wrist shot in golf—The follow-through—Timing of the body action—Arms and hands high up at the finish—How bad drives are made—The causes of slicing—When the ball is pulled—Misapprehensions as to slicing and pulling—Dropping of the right shoulder—Its evil consequences—No trick in long driving—Hit properly and hard—What is pressing and what is not—Summary of the drive.

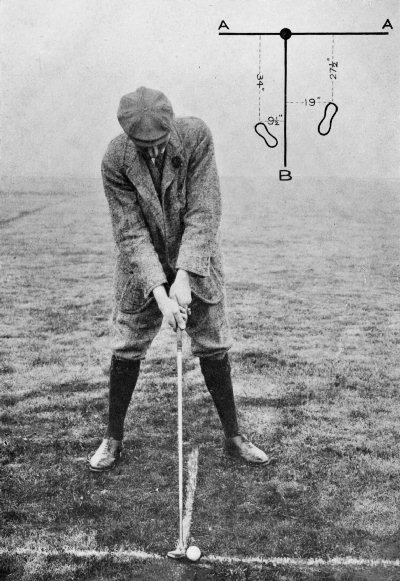

Now let us consider the upward and downward swings of the club, and the movements of the arms, legs, feet, and body in relation to them. As a first injunction, it may be stated that the club should be drawn back rather more slowly than you intend to bring it down again. "Slow back" is a golfing maxim that is both old and wise. The club should begin to gain speed when the upward swing is about half made, and the increase should be gradual until the top is reached, but it should never be so fast that control of the club is to any extent lost at the turning-point. The head of the club should be taken back fairly straight from the ball—along the A line—for the first six inches, and after that any tendency to sweep it round sharply to the back should be avoided. Keep it very close to the straight line until it is half-way up. The old St. Andrews style of driving largely consisted in this sudden sweep round, but the modern method appears to be easier and productive of better results. So this carrying of the head of the club[Pg 65] upwards and backwards seems to be a very simple matter, capable of explanation in a very few words; but, as every golfer of a month's experience knows, there is a long list of details to be attended to, which I have not yet named, each of which seems to vie with the others in its attempt to destroy the effectiveness of the drive. Let us begin at the top, as it were, and work downwards, and first of all there is the head of the golfer to consider.

The head should be kept perfectly motionless from the time of the address until the ball has been sent away and is well on its flight. The least deviation from this rule means a proportionate danger of disaster. When a drive has been badly foozled, the readiest and most usual explanation is that the eye has been taken off the ball, and the wise old men who have been watching shake their heads solemnly, and utter that parrot-cry of the links, "Keep your eye on the ball." Certainly this is a good and necessary rule so far as it goes; but I do not believe that one drive in a hundred is missed because the eye has not been kept on the ball. On the other hand, I believe that one of the most fruitful causes of failure with the tee shot is the moving of the head. Until the ball has gone, it should, as I say, be as nearly perfectly still as possible, and I would have written that it should not be moved to the extent of a sixteenth of an inch, but for the fact that it is not human to be so still, and golf is always inclined to the human side. When the head has been kept quite still and the club has reached the top of the upward swing, the eyes should be looking over the middle of the left shoulder, the left one being dead over the centre of that shoulder. Most players at one time or another, and the best of them when they are a little off their game, fall into every trap that the evil spirits of golf lay for them, and unconsciously experience a tendency to lift the head for five or six inches away from the ball while the upward swing is being taken. This is often what is imagined to be taking the eye off the ball, particularly as, when it is carried to excess, the[Pg 66] eye, struggling gallantly to do its duty, finds considerable difficulty in getting a sight of the ball over the left shoulder, and sometimes loses it altogether for an instant. An examination of the photograph showing the top of the swing (Plate VII.) will make it clear that there is very little margin for the moving of the head if the ball is to be kept in full view for the whole of the time.

In the upward swing the right shoulder should be raised gradually. It is unnecessary for me to submit any instruction on this point, since the movement is natural and inevitable, and there is no tendency towards excess; but the arms and wrists need attention. From the moment when the club is first taken back the left wrist should begin to turn inwards (that is to say, the movement is in the same direction as that taken by the hands of a clock), and so turn away the face of the club from the ball. When this is properly done, the toe of the club will point to the sky when it is level with the shoulder and will be dead over the middle of the shaft. This turning or twisting process continues all the way until at the top of the swing the toe of the club is pointing straight downwards to the ground. A reference to Plate VII. will show that this has been done, and that as the result the left wrist finishes the upward swing underneath the shaft, which is just where it ought to be. When the wrist has not been at work in the manner indicated, the toe of the club at the top of the drive will be pointing upwards. In order to satisfy himself properly about the state of affairs thus far in the making of the drive, the golfer should test himself at the top of the swing by holding the club firmly in the position which it has reached, and then dropping the right hand from the grip. He will thus be enabled to look right round, and if he then finds that the maker's name on the head of the club is horizontal, he will know that he has been doing the right thing with his wrists, while if it is vertical the wrist action has been altogether wrong.

During the upward swing the arms should be gradually[Pg 67] let out in the enjoyment of perfect ease and freedom (without being spread-eagled away from the body) until at the top of the swing the left arm, from the shoulder to the elbow, is gently touching the body and hanging well down, while the right arm is up above it and almost level with the club. The picture indicates exactly what I mean, and a reference to the illustration showing what ought not to be the state of affairs generally when the top of the swing is reached (Plate XI.), should convince even the veriest beginner how much less comfortable is the position of the arms in this instance than when the right thing has been done, and how laden with promise is the general attitude of the player in the latter position as compared with his cramped state in the former. I think I ought to state, partly in justice to myself, and partly to persuade my readers that the best way in this case, as in all others, is the most natural, that I found it most inconvenient and difficult to make such extremely inaccurate swings as those depicted in this and other photographs of the "How not to do it" series, although they are by no means exaggerations of what are seen on the links every day, even players of several years' experience being constantly responsible for them.

In the upward movement of the club the body must pivot from the waist alone, and there must be no swaying, not even to the extent of an inch. When the player sways in his drive the stroke he makes is a body stroke pure and simple. The body is trying to do the work the arms should do, and in these circumstances it is impossible to get so much power into the stroke as if it were properly made, while once more the old enemies, the slice and the pull, will come out from their hiding-places with their mocking grin at the unhappy golfer.

The movements of the feet and legs are important. In addressing the ball you stand with both feet flat and securely placed on the ground, the weight equally divided between them, and the legs so slightly bent at the knee joints as to[Pg 68] make the bending scarcely noticeable. This position is maintained during the upward movement of the club until the arms begin to pull at the body. The easiest and most natural thing to do then, and the one which suggests itself, is to raise the heel of the left foot and begin to pivot on the left toe, which allows the arms to proceed with their uplifting process without let or hindrance. Do not begin to pivot on this left toe ostentatiously, or because you feel you ought to do so, but only when you know the time has come and you want to, and do it only to such an extent that the club can reach the full extent of the swing without any difficulty. While this is happening it follows that the weight of the body is being gradually thrown on to the right leg, which accordingly stiffens until at the top of the swing it is quite rigid, the left leg being at the same time in a state of comparative freedom, slightly bent in towards the right, with only just enough pressure on the toe to keep it in position.

To the man who has never driven a good ball in his life this process must seem very tedious. All these things to attend to, and something less than a second in which to attend to them! It only indicates how much there is in this wonderful game—more by far than any of us suspect or shall ever discover. But the time comes, and it should come speedily, when they are all accomplished without any effort, and, indeed, to a great extent, unconsciously. The upward swing is everything. If it is bad and faulty, the downward swing will be wrong and the ball will not be properly driven. If it is perfect, there is a splendid prospect of a long and straight drive, carrying any hazard that may lie before the tee. That is why so very much emphasis must be laid on getting this upward swing perfect, and why comparatively little attention need be paid to the downward swing, even though it is really the effective part of the stroke.

Be careful not to dwell at the turn of the swing. The club has been gaining in speed right up to this point, and though I suppose that, theoretically, there is a pause at the[Pg 69] turning-point, lasting for an infinitesimal portion of a second, the golfer should scarcely be conscious of it. He must be careful to avoid a sudden jerk, but if he dwells at the top of the stroke for only a second, or half that short period of time, his upward swing in all its perfection will have been completely wasted, and his stroke will be made under precisely the same circumstances and with exactly the same disadvantages as if the club had been poised in this position at the start, and there had been no attempt at swinging of any description. In such circumstances a long ball is an impossibility, and a straight one a matter of exceeding doubt. The odds are not very greatly in favour of the ball being rolled off the teeing ground. So don't dwell at the turn; come back again with the club.

The club should gradually gain in speed from the moment of the turn until it is in contact with the ball, so that at the moment of impact its head is travelling at its fastest pace. After the impact, the club head should be allowed to follow the ball straight in the line of the flag as far as the arms will let it go, and then, having done everything that is possible, it swings itself out at the other side of the shoulders. The entire movement must be perfectly smooth and rhythmical; in the downward swing, while the club is gaining speed, there must not be the semblance of a jerk anywhere such as would cause a jump, or a double swing, or what might be called a cricket stroke. That, in a few lines, is the whole story of the downward swing; but it needs some little elaboration of detail. In the first place, avoid the tendency—which is to some extent natural—to let the arms go out or away from the body as soon as the downward movement begins. When they are permitted to do so the club head escapes from its proper line, and a fault is committed which cannot be remedied before the ball is struck. Knowing by instinct that you are outside the proper course, you make a great effort at correction, the face of the club is drawn across the ball, and there is one more slice. The arms should be kept[Pg 70] fairly well in during the latter half of the downward swing, both elbows almost grazing the body. If they are properly attended to when the club is going up, there is much more likelihood of their coming down all right.

The head is still kept motionless and the body pivots easily at the waist; but when the club is half-way down, the left hip is allowed to go forward a little—a preliminary to and preparation for the forward movement of the body which is soon to begin. The weight is being gradually moved back again from the right leg to the left. At the moment of impact both feet are equally weighted and are flat on the ground, just as they were when the ball was being addressed; indeed, the position of the body, legs, arms, head, and every other detail is, or ought to be, exactly the same when the ball is being struck as they were when it was addressed, and for that reason I refer my readers again to the photograph of the address (No. VI.) as the most correct position of everything at the moment of striking. After the impact the weight is thrown on to the left leg, which stiffens, while the right toe pivots and the knee bends just as its partner did in the earlier stage of the stroke, but perhaps to a greater extent, since there is no longer any need for restraint.

Now pay attention to the wrists. They should be held fairly tightly. If the club is held tightly the wrists will be tight, and vice vers�. When the wrists are tight there is little play in them, and more is demanded of the arms. I don't believe in the long ball coming from the wrists. In defiance of principles which are accepted in many quarters, I will go so far as to say that, except in putting, there is no pure wrist shot in golf. Some players attempt to play their short approaches with their wrists as they have been told to do. These men are likely to remain at long handicaps for a long time. Similarly there is a kind of superstition that the elect among drivers get in some peculiar kind of "snap"—a momentary forward pushing movement—with their wrists at the time of impact, and that it is this wrist work at the[Pg 71] critical period which gives the grand length to their drives, those extra twenty or thirty yards which make the stroke look so splendid, so uncommon, and which make the next shot so much easier. Generally speaking, the wrists when held firmly will take very good care of themselves; but there is a tendency, particularly when the two-V grip is used, to allow the right hand to take charge of affairs at the time the ball is struck, and the result is that the right wrist, as the swing is completed, gradually gets on to the top of the shaft instead of remaining in its proper place. The consequence is a pulled ball,—in fact, this is just the way in which I play for a pull. When the fault is committed to a still greater extent, the head of the club is suddenly turned over, and then the ball is foundered, as we say,—that is, it is struck downwards, and struggles, crippled and done for, a few yards along the ground in front of the tee. I find that ladies are particularly addicted to this very bad habit. Once again I have to say that if the club is taken up properly there is the greater certainty of its coming down properly, and then if you keep both hands evenly to their work there is a great probability of a good follow-through being properly effected.

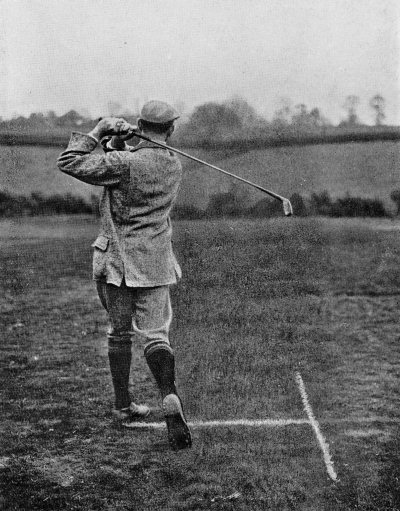

When the ball has been struck, and the follow-through is being accomplished, there are two rules, hitherto held sacred, which may at last be broken. With the direction and force of the swing your chest is naturally turned round until it is facing the flag, and your body now abandons all restraint, and to a certain extent throws itself, as it were, after the ball. There is a great art in timing this body movement exactly. If it takes place the fiftieth part of a second too soon the stroke will be entirely ruined; if it comes too late it will be quite ineffectual, and will only result in making the golfer feel uneasy and as if something had gone wrong. When made at the proper instant it adds a good piece of distance to the drive, and that instant, as explained, is just when the club is following through. An examination of the photograph indicating the finish of the swing (No. IX.)[Pg 72] will show how my body has been thrown forward until at this stage it is on the outward side of the B line, although it was slightly on the other side when the ball was being addressed. Secondly, when the ball has gone, and the arms, following it, begin to pull, the head, which has so far been held perfectly still, is lifted up so as to give freedom to the swing, and incidentally it allows the eyes to follow the flight of the ball.

PLATE X. HOW NOT TO DRIVE

In this case the player's feet are much to close together, and there is a space between the hands as there should never be, whatever style of grip is favored. Also the right hand is too much underneath the shaft. The result of these faults will usually be a pulled ball, but a long drive of any sort is impossible.

PLATE XI. HOW NOT TO DRIVE

In this case the left wrist instead of being underneath the handle is level with it—a common and dangerous fault. The left arm is spread-eagled outwards, and the toe of the club is not pointing downwards as it ought to be. The pivoting on the left toe is very imperfect. There is no power in this position. Sometimes the result is a pull, but frequently the ball will be foundered. No length is possible.

PLATE XII. HOW NOT TO DRIVE

This is an example of a bad finish. Instead of being thrown forward after the impact the body has fallen away. The usual consequence is a sliced ball, and this is also one of the commonest causes of short driving.

PLATE XIII. HOW NOT TO DRIVE

Here again the body has failed to follow the ball after impact. The stance is very bad, the forward position of the left foot preventing a satisfactory follow-through. The worst fault committed here, however, is the position taken by the left arm. The elbow is far too low. It should be at least as high as the right elbow. Result—complete lack of power and length.

I like to see the arms finish well up with the hands level with the head. This generally means a properly hit ball and a good follow-through. At the finish of the stroke the right arm should be above the left, the position being exactly the reverse of that in which the arms were situated at the top of the swing, except that now the right arm is not quite so high as the left one was at the earlier stage. The photograph (No. IX.) indicates that the right arm is some way below the level of the shaft of the club, whereas it will be remembered that the left arm was almost exactly on a level with it. Notice also the position of the wrists at the finish of the stroke.

Having thus indicated at such great length the many points which go to the making of a good drive, a long one and a straight one, yet abounding with ease and grace, allow me to show how some of the commonest faults are caused by departures from the rules for driving. Take the sliced ball, as being the trouble from which the player most frequently suffers, and which upon occasion will exasperate him beyond measure. When a golfer is slicing badly almost every time, it is frequently difficult for him to discover immediately the exact source of the trouble, for there are two or three ways in which it comes about. The player may be standing too near to the ball; he may be pulling in his arms too suddenly as he is swinging on to it, thus drawing the club towards his left foot; or he may be falling on to the ball at the moment of impact. When the stance is taken too near to the ball there is a great inducement to the arms to take a course[Pg 73] too far outwards (in the direction of the A line) in the upward swing. The position is cramped, and the player does not seem able to get the club round at all comfortably. When the club head is brought on to the ball after a swing of this kind, the face is drawn right across it, and a slice is inevitable. In diagnosing the malady, in cases where the too close stance is suspected, it is a good thing to apply the test of distance given at the beginning of the previous chapter, and see whether, when the club head is resting in position against the teed ball, the other end of the shaft just reaches to the left knee when it is in position, and has only just so much bend in it as it has when the ball is being addressed. The second method of committing the slicing sin is self-explanatory. As for the third, a player falls on the ball, or sways over in the direction of the tee (very slightly, but it is the trifles that matter most) when his weight has not been properly balanced to start with, and when in the course of the swing it has been moved suddenly from one leg to the other instead of quite gradually. But sometimes falling on the ball is caused purely and simply by swaying the body, against which the player has already been warned. When the slicing is bad, the methods of the golfer should be tested for each of these irregularities, and he should remember that an inch difference in any position or movement as he stands upon the tee is a great distance, and that two inches is a vast space, which the mind trained to calculate in small fractions can hardly conceive.

Pulling is not such a common fault, although one which is sometimes very annoying. Generally speaking, a pulled ball is a much better one than one which has been sliced, and there are some young players who are rather inclined to purr with satisfaction when they have pulled, for, though the ball is hopelessly off the line, they have committed an error which is commoner with those whose hair has grown grey on the links than with the beginner whose handicap is reckoned by eighteen or twenty strokes. But after all pulling is not[Pg 74] an amusement, and even when it is an accomplishment and not an accident, it should be most carefully regulated. It is the right hand which is usually the offender in this case. The wrist is wrong at the moment of impact, and generally at the finish of the stroke as well,—that is, it is on the top of the club, indicating that the right hand has done most of the work. In a case of this sort the top edge of the face of the club is usually overlapping the bottom edge, so that the face is pointing slightly downwards at the moment of impact; and when this position is brought about with extreme suddenness the ball is frequently foundered. If it escapes this fate, then it is pulled. A second cause of pulling is a sudden relaxation of the grip of the right hand at the time of hitting the ball. When this happens, the left hand, being uncontrolled, turns over the club head in the same manner as in the first case, and the result is the same.

I have found from experience that it is necessary to enjoin even players of some years' standing to make quite certain that they are slicing and pulling, before they complain about their doing so and try to find cures for it. In a great number of cases a player will take his stance in quite the wrong direction, either too much round to the right or too much to the left, and when the ball has flown truly along the line on which it was despatched, the golfer blandly remarks that it was a bad slice or a bad pull, as the case may be. He must bring himself to understand that a ball is neither sliced nor pulled when it continues flying throughout in the direction in which it started from the tee. It is only when it begins performing evolutions in the air some distance away, and taking a half wheel to the right or left, that it has fallen a victim to the slice or pull.

There is one more fault of the drive which must be mentioned. It is one of the commonest mistakes that the young golfer makes, and one which afflicts him most keenly, for when he makes it his drive is not a drive at all; all his power, or most of it, has been expended on the turf some[Pg 75] inches behind the ball. The right shoulder has been dropped too soon or too low. During the address this shoulder is necessarily a little below the left one, and care must be taken at this stage that it is not allowed to drop more than is necessary. At the top of the swing the right shoulder is naturally well above the other one, and at the moment of impact with the ball it should just have resumed its original position slightly below the left. It often happens, however, that even very good golfers, after a period of excellent driving, through sheer over-confidence or carelessness, will fall into the way of dropping the right shoulder too soon, or, when they do drop it, letting it go altogether, so that it fairly sinks away. The result is exactly what is to be expected. The head of the club naturally comes down with the shoulder and flops ineffectually upon the turf behind the tee, anything from two to nine inches behind the ball. Yet, unless the golfer has had various attacks of this sort of thing before, he is often puzzled to account for it. The remedy is obvious.

I can imagine that many good golfers, now that I near the end of my hints on driving, may feel some sense of disappointment because I have not given them a recipe for putting thirty or forty yards on to their commonplace drives. I can only say that there is no trick or knack in doing it, as is often suspected, such as the suggestion, already alluded to, that the wrists have a little game of their own just when the club head is coming in contact with the ball. The way to drive far is to comply with the utmost care with every injunction that I have set forth, and then to hit hard but by the proper use of the swing. To some golfers this may be a dangerous truth, but it must be told: it is accuracy and strength which make the long ball. But I seem to hear the young player wail, "When I hit hard you say 'Don't press!'" A golfer is not pressing when he swings through as fast as he can with his club, gaining speed steadily, although he is often told that he is. But it most frequently happens that[Pg 76] when he tries to get this extra pace all at once, and not as the result of gradual improvement and perfection of style, that it comes not smoothly but in a great jerk just before the ball is reached. This is certainly the way that it comes when the golfer is off his game, and he tries, often unconsciously, to make up in force what he has temporarily lost in skill. This really is pressing, and it is this against which I must warn every golfer in the same grave manner that he has often been warned before. But to the player who, by skill and diligence of practice, increases the smooth and even pace of his swing, keeping his legs, body, arms, and head in their proper places all the time, I have nothing to give but encouragement, though long before this he himself will have discovered that he has found out the wonderful, delightful secret of the long ball.

Two chapters of detailed instruction are too much for a player to carry in his mind when he goes out on to the links to practise drives, and for his benefit I will here make the briefest possible summary of what I have already stated. Let him attend, then, to the following chief points:�

Stance.—The player should stand just so far away from the ball, that when the face of the driver is laid against it in position for striking, the other end of the shaft exactly reaches to the left knee when the latter is slightly bent. The right foot may be anything up to seven inches in front of the left, but certainly never behind it. The left toe should be a trifle in advance of the ball. The toes should be turned outwards. Make a low tee.

Grip.—As described. Remember that the palm of the right hand presses hard on the left thumb at all times except when nearing and at the top of the swing. The grip of the thumb and the first two fingers of each hand is constantly firm.

Upward Swing.—The club head must be taken back in a straight line for a few inches, and then brought round gradually—not too straight up (causing slicing) nor too far[Pg 77] round in the old-fashioned style. The speed of the swing increases gradually. The elbows are kept fairly well in, the left wrist turning inwards and finishing the upward swing well underneath the shaft. The body must not be allowed to sway. It should pivot easily from the waist. The head must be kept quite still. The weight is gradually thrown entirely on to the right leg, the left knee bends inwards, the left heel rises, and the toe pivots. There must be no jerk at the turn of the swing.

Downward Swing.—There should be a gradual increase of pace, but no jerk anywhere. The arms must be kept well down when the club is descending, the elbows almost grazing the body. The right wrist should not be allowed to get on to the top of the club. The head is still motionless. The left hip is allowed to move forward very slightly while the club is coming down. The weight of the body is gradually transferred from the right leg to the left, the right toe pivoting after the impact, and the left leg stiffening. The right shoulder must be prevented from dropping too much. After the impact the arms should be allowed to follow the ball and the body to go forward, the latter movement being timed very carefully. The head may now be raised. Finish with the arms well up the right arm above the left.

Slicing.This may be caused by standing too near to the ball, by pulling in the arms, or by falling on the ball.

Pulling.Usually the result of the club head being turned partly over when the ball is struck, or, alternatively, by relaxing the grip with the right hand.

Of course, to drive a golf ball well is a golfing skill which is not going to be learned in a week or a month.