THE COMPLETE GOLFER

By Harry Vardon

CHAPTER VIIISPECIAL STROKES WITH WOODEN CLUBS

The master stroke in golf—Intentional pulling and slicing—The contrariness of golf—When pulls and slices are needful—The stance for the slice—The upward swing—How the slice is made—The short sliced stroke—Great profits that result—Warnings against irregularities—How to pull a ball—The way to stand—The work of the right hand—A feature of the address—What makes a pull—Effect of wind on the flight of the ball—Greatly exaggerated notions—How wind increases the effect of slicing and pulling—Playing through a cross wind—The shot for a head wind—A special way of hitting the ball—A long low flight—When the wind comes from behind.

Which is the master stroke in golf?

Good question!

Is it the perfect drive, with every limb, muscle, and organ of the body working in splendid harmony with the result of blasting the ball well beyond two hundred yards in a straight line from the tee? No, it is not that, for there are some thousands of players who can drive what is to all intents and purposes a perfect ball without any unusual effort. Is it the brassy shot which is equal to a splendid drive, and which, delivering the ball in safety over the last hazard, places it nicely upon the green, absolving the golfer from the necessity of playing any other approach? No, though that is a most creditable achievement. Is it the approach over a threatening bunker on to a difficult green where the ball can hardly be persuaded to remain, yet so deftly has the cut been applied, and so finely has the strength been judged, that it stops dead against the hole, and for a certainty a stroke is saved? This is a most satisfying shot which has in its time[Pg 86] won innumerable holes, but it is not the master stroke of golf. Then, is it the putt from the corner of the green across many miniature hills and dales with a winding course over which the ball must travel, often far away from the direct line, but which carries it at last delightfully to the opening into which it sinks just as its strength is ebbing away? We all know the thrilling ecstasy that comes from such a stroke as this, but it has always been helped by a little good luck, and I would not call it the master stroke. There are inferior players who are good putters. Which, then, is the master stroke? I say that it is the ball struck by any club to which a big pull or slice is intentionally applied for the accomplishment of a specific purpose which could not be achieved in any other way, and nothing more exemplifies the curious waywardness of this game of ours than the fact that the stroke which is the confounding and torture of the beginner who does it constantly, he knows not how, but always to his detriment, should later on at times be the most coveted shot of all, and should then be the most difficult of accomplishment. I call it the master shot because, to accomplish it with any certainty and perfection, it is so difficult even to the experienced golfer, because it calls for the most absolute command over the club and every nerve and sinew of the body, and the courageous heart of the true sportsman whom no difficulty may daunt, and because, when properly done, it is a splendid thing to see, and for a certainty results in material gain to the man who played it.

I will try, then, to give the golfers who desire them some hints as to how by diligence and practice they may come to accomplish these master strokes; but I would warn them not to enter into these deepest intricacies of the game until they have completely mastered all ordinary strokes with their driver or brassy and can absolutely rely upon them, and even then the intentional pull and slice should only be attempted when there is no way of accomplishing the purpose which is likely to be equally satisfactory. Thus, when a long brassy[Pg 87] shot to the green is wanted, and one is most completely stymied by a formidable tree somewhere in the foreground or middle distance, the only way to get to the hole is by working round the tree, either from the right or from the left, and this can be done respectively by the pull and the slice. Of the two, the sliced shot is the easier, and is to be recommended when the choice is quite open, though it must not be overlooked that the pulled ball is the longer. The slicing action is not quite so quick and sudden, and does not call for such extremely delicate accuracy as the other, and therefore we will deal with it first.

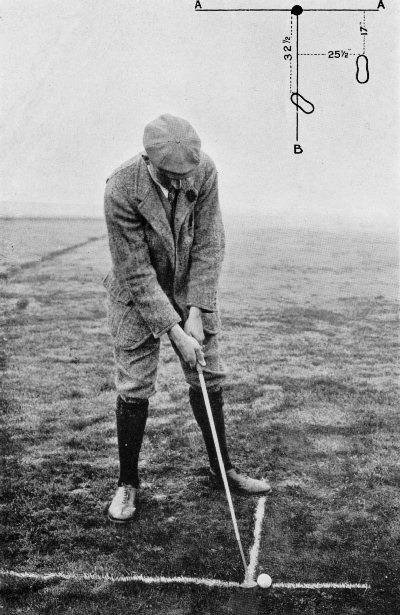

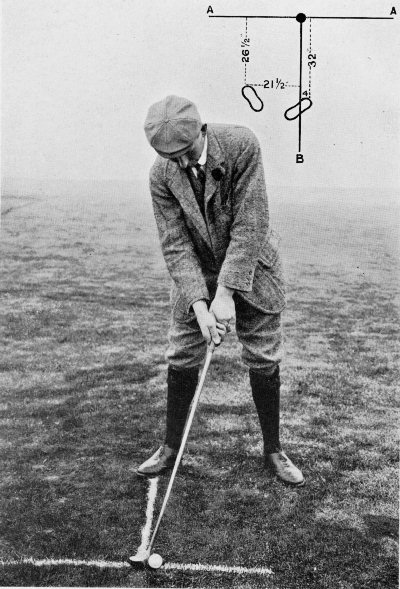

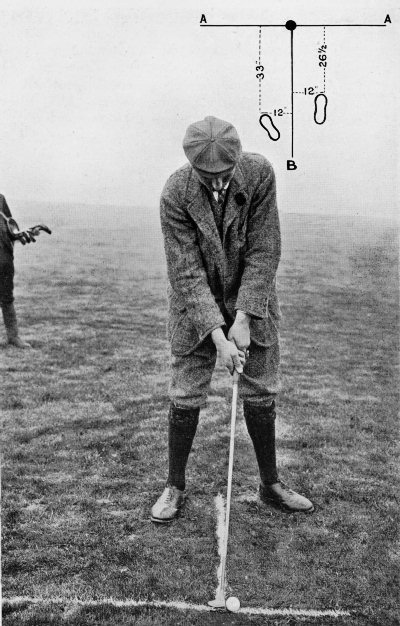

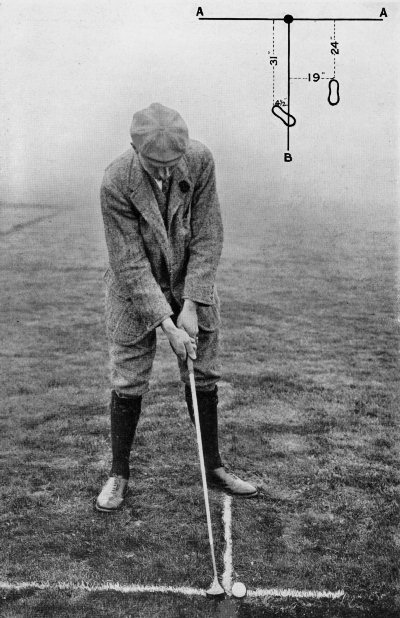

The golfer should now pay very minute attention to the photographs (Nos. XIV., XV., and XVI.) which were specially taken to illustrate these observations. It will be noticed at once that I am standing very much more behind the ball than when making an ordinary straight drive or brassy stroke, and this is indeed the governing feature of the slicing shot as far as the stance and position of the golfer, preparatory to taking it, are concerned. An examination of the position of the feet, both in the photograph (XIV.) and the accompanying diagram, will show that the left toe is now exactly on the B line, that is to say, it is just level with the ball, while the right foot is 25½ inches away from the same mark, whereas in the case of the ordinary drive it was only 19. At the same time the right foot has been moved very much nearer to the A line, more than 10 inches in fact, although the left is only very slightly nearer. Obviously the general effect of this change of stance is to move the body slightly round to the left. There is no mystery as to how the slice is made. It comes simply as the result of the face of the club being drawn across the ball at the time of impact, and it was precisely in this way that it was accidentally accomplished when it was not wanted. In addressing the ball there should be just the smallest trifle of extra weight thrown on the right leg; but care must be taken that this difference is not exaggerated. The golfer should be scarcely conscious of it.

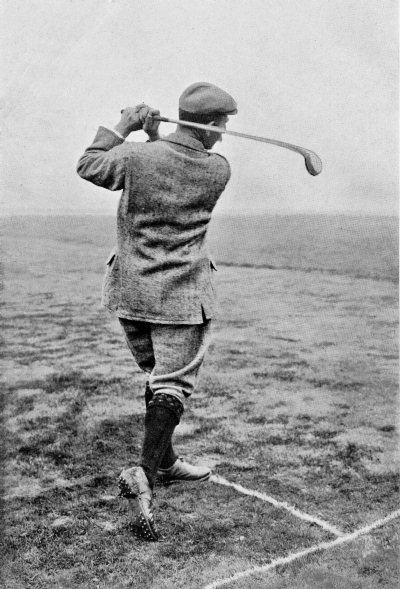

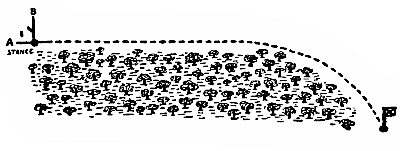

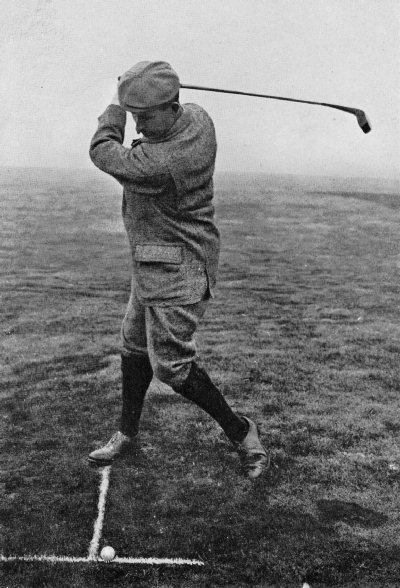

The grip is made in the usual manner, but there is a very material and all-important difference in the upward swing. In its upward movement the club head now takes a line distinctly outside that which is taken in the case of the ordinary drive, that is to say, it comes less round the body and keeps on the straight line longer. When it is half-way up it should be about two or three inches outside the course taken for the full straight drive. The object of this is plain. The inflexible rule that as the club goes up so will it come down, is in operation again. The club takes the same line on the return, and after it has struck the ball it naturally, pursuing its own direction, comes inside the line taken in the case of the ordinary drive. The result is that at the moment of impact, and for that fractional part of a second during which the ball may be supposed to be clinging to the club, the face of the driver or brassy is being, as it were, drawn across the ball as if cutting a slice out of it. There is no means, so far as I know, of gauging how unthinkably short is the time during which this slicing process is going on, but, as we observed, when we were slicing unintentionally and making the ball curl round sometimes to an angle of ninety degrees before the finish of its flight, it is quite long enough to effect the most radical alteration in what happens afterwards. In that short space of time a spinning motion is put upon the ball, and a curious impulse which appears to have something in common with that given to a boomerang is imparted, which sooner or later take effect. In other respects, when a distant slice is wanted, the same principles of striking the ball and finishing the swing as governed the ordinary drive are to be observed. What I mean by a distant slice is one in which the ball is not asked to go round a corner until it is well on its way, the tree, or whatever it is that has to be circumvented, being half-way out or more, as shown in the diagram on opposite page. This is the most difficult kind of slice to perform, inasmuch as the ball must be kept on a straight line until the object is approached,[Pg 89] and then made to curl round it as if by instinct. In such a case the club should be drawn very gradually across, and not so much or so suddenly as when the slice is wanted immediately.

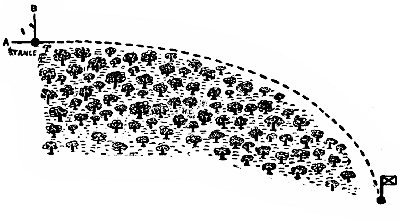

When the tree or thicket that stymies you is only twenty or thirty yards away, the short sliced shot is not only the best but perhaps the only one to play, that is to say, if it is first-class golf that is being practised and there is an opponent who is fighting hard. Take a case for exemplification—one which is of the commonest occurrence. There is a long hole to be played, and some thirty yards from the point which will be reached by a good drive, but well away to the right there is a spinny of tall trees. The golfer is badly off the line with his drive, with the result that he now has the trees in the direct line between him and the hole which is the best part of a hundred yards from the other edge of the wood, or say a hundred and forty from where the ball is lying. He might by a wonderfully lofted shot play the ball over the obstacle, but he would have to rise at such an angle that any length would be an impossibility, and he would be short of the green. The only alternative to the slice would be to accept the loss of a stroke as inevitable, play away to the right or left, and then get on to the green with the next one. Thus in either case a valuable stroke is lost, and if the enemy is playing the correct game the loss may be most serious. The short or quick slice[Pg 90] comes to the rescue admirably. Turn the ball round the spinny, give it as much length as you can in the circumstances, and if the job has been well done you will be on the green after all with the highly comforting sensation that for once you have proved yourself a golfer of the first degree of skill, and have snatched a half when the hole seemed lost. The diagram here presented illustrates the best possibilities of a quick slice. I can explain in a line exactly how this is done, but I cannot guarantee that my readers will therefore be able to do it until they have practised, and practised, and practised yet again. Instead of hitting the ball with the middle of the club face as in playing for the distant slice as already explained, hit it slightly nearer the heel of the club. Swing upwards in the same way, and finish in the same way, also. Taking the ball with the heel results in the slice being put on more quickly and in there being more of it, but I need hardly observe that the stroke must be perfectly judged and played, and that there must be no flaw in it anywhere, or disaster must surely follow. As I say, it is not an easy shot to accomplish, but it is a splendid thing to do when wanted, and I strongly recommend the golfer who has gained proficiency in the ordinary way with his wooden clubs, to practise it whenever possible until at length he feels some confidence[Pg 91] in playing it. It is one of those strokes which mark the skilled and resourceful man, and which will win for him many a match. Beyond the final admonition to practise, I have only one more piece of advice to give to the golfer who wants to slice when a slice would be useful, and that is in the downward swing he must guard against any inclination to pull in the arms too quickly, the result of his consciousness that the club has to be drawn across the ball. Whatever is necessary in this way comes naturally as the consequence of taking the club head more outwards than usual in the upward swing. Examine the photographs very carefully in conjunction with the study of all the observations that I have made.

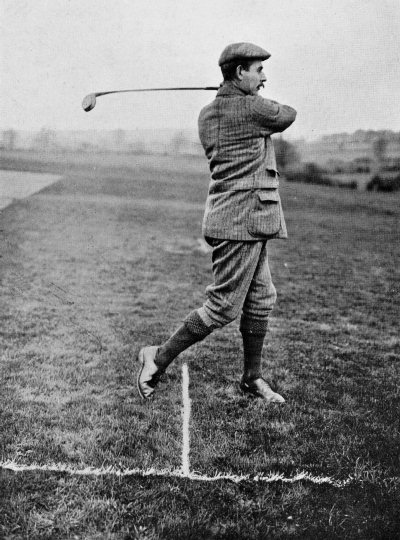

Now there is the pulled ball to consider; for there are times when the making of such a shot is eminently desirable. Resort to a slice may be unsatisfactory, or it may be entirely impossible, and one important factor in this question is that the pulled ball is always much longer than the other, in fact it has always so much length in it that many players in driving in the ordinary way from the tee, and desiring only to go straight down the course, systematically play for a pull and make allowances for it in their direction. Now examine Plate XVII. and the accompanying diagram illustrating the stance for the pull, and see how very materially it differs from those which were adopted for the ordinary drive and that in which a slice was asked for. We have moved right round to the front of the ball. The right heel is on the B line and the toe 4 inches away from it, while the left toe is no less than 21½ inches from this line, and therefore so much in front of the ball. At the same time the line of the stance shows that the player is turned slightly away from the direction in which he proposes to play, the left toe being now only 26½ inches away from the A line, while the right toe is 32 inches distant from it. The obvious result of this stance is that the handle of the club is in front of the ball, and this circumstance must be accentuated by the hands being held even slightly more forward than for an[Pg 92] ordinary drive. Now they are held forward in front of the head of the club. In the grip there is another point of difference. It is necessary that in the making of this stroke the right hand should do more work than the left, and therefore the club should be held rather more loosely by the left hand than by its partner. The latter will duly take advantage of this slackness, and will get in just the little extra work that is wanted of it. In the upward swing carry the club head just along the line which it would take for an ordinary drive. The result of all this arrangement, and particularly of the slackness of the left hand and comparative tightness of the right, is that there is a tendency in the downward swing for the face of the club to turn over to some extent, that is, for the top edge of it to be overlapping the bottom edge. This is exactly what is wanted, for, in fact, it is quite necessary that at the moment of impact the right hand should be beginning to turn over in this manner, and if the stroke is to be a success the golfer must see that it does so, but the movement must be made quite smoothly and naturally, for anything in the nature of a jab, such as is common when too desperate efforts are made to turn over an unwilling club, would certainly prove fatal. It follows from what has been happening all the way through, that at the finish of the stroke the right hand, which has matters pretty well its own way, has assumed final ascendancy and is well above the left. Plates XVIII. and XIX. should be carefully examined.

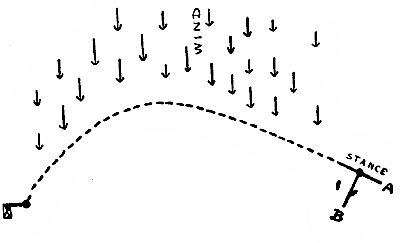

The pulled ball is particularly useful in a cross wind, and this fact leads us naturally to a consideration of the ways and means of playing the long shot with the wooden club to the best advantage when there are winds of various kinds to test the resources of the golfer. Now, however, that this question is raised, I feel it desirable to say without any hesitation that the majority of golfers possess vastly exaggerated notions of the effect of strong cross winds on the flight of their ball. They greatly overestimate the[Pg 93] capabilities of a breeze. To judge by their observations on the tee, one concludes that a wind from the left is often sufficient to carry the ball away at an angle of forty-five degrees, and indeed sometimes, when it does take such an exasperating course, and finishes its journey some fifty yards away from the point to which it was desired to despatch it, there is an impatient exclamation from the disappointed golfer, "Confound this wind! Who on earth can play in a hurricane!" or words to that effect. Now I have quite satisfied myself that only a very strong wind indeed will carry a properly driven ball more than a very few yards out of its course, and in proof of this I may say that it is very seldom when I have to deal with a cross wind that I do anything but play straight at the hole without any pulling or slicing or making allowances in any way. If golfers will only bring themselves to ignore the wind, then it in turn will almost entirely ignore their straight ball. When you find your ball at rest the aforementioned forty or fifty yards from the point to which you desired to send it, make up your mind, however unpleasant it may be to do so, that the trouble is due to an unintentional pull or slice, and you may get what consolation you can from the fact that the slightest of these variations from the ordinary drive is seized upon with delight by any wind, and its features exaggerated to an enormous extent. It is quite possible, therefore, that a slice which would have taken the ball only twenty yards from the line when there was no wind, will take it forty yards away with the kind assistance of its friend and ally.

However, I freely admit that there are times when it is advisable to play a fancy shot when there is an excess of wind, and the golfer must judge according to circumstances. Let me give him this piece of advice: very rarely slice as a remedy against a cross wind. Either pull or nothing. If there is a strong wind coming from the right, the immature golfer who has been practising slices argues that this is his chance, and that it is his obvious duty to slice his ball right[Pg 94] into the teeth of that wind, so that wind and slice will neutralise each other, and the ball as the result will pursue an even course in the straight line for the flag. A few trials will prove to him that this is a very unsatisfactory business, and after he has convinced himself about it I would recommend him to try pulling the ball and despatching it at once along a line to the right directly against that same wind. When the pull begins to operate, both this and the wind will be working together, and the ball will be carried a much greater length, its straightness depending upon the accuracy of allowance. The diagram explains my meaning. But I reiterate that the ordinary shots are generally the easiest and best with which to get to the hole. The principle of the golfer should be, and I trust is, that he always wants to reach the hole in the simplest and easiest way, with a minimum of doubt and anxiety about any shot which he is called upon to play, and one usually finds that without these fancy shots one comes to the flag as easily as is possible in all the circumstances. Of course I am writing more particularly with the wind in mind, and am not recommending the ordinary shot when there is a tree or a spinny for a stymie, in contradiction to what I have said earlier in this chapter.

However, there is one kind of wind difficulty which it is certainly necessary to deal with by a departure from the ordinary method of play with the driver or the brassy, and that is when the wind is blowing straight up to the player from the hole, threatening to cut off all his distance. Unless measures are taken to prevent it, a head wind of this description certainly does make play extremely difficult, the comparative shortness of the drive making an unduly long approach shot necessary, or even demanding an extra stroke at long holes in order to reach the green. But, fortunately, we have discovered a means of dealing very satisfactorily with these cases. What we want to do is to keep the ball as low down as possible so as to cheat the wind, for the lower the ball the less opportunity has the breeze of getting to work upon it. A combination of two or three methods is found to be the best for obtaining this low turf-skimming ball, which yet has sufficient driving power in it to keep up until it has achieved a good length. Evidently the first thing to do is to make the tee... if it is a tee shot... rather lower than usual... as low as is consistent with safety and a clean stroke. The player should then stand rather more in front of the ball than if he were playing for an ordinary drive, but this forward position should not by any means be so marked as it was in the stance for the pulled drive. A reference to Plate XX. and the diagram will show that now we have the ball exactly half-way between the toes, each toe being twelve inches to the side of the B line, while both are an inch nearer to the ball than was the case when the ordinary drive was being made. But the most important departure that we make from the usual method of play is in the way we hit the ball. So far we have invariably been keeping our gaze fixed on a point just behind it, desiring that the club shall graze the ground and take the ball rather below the centre. But now it is necessary that the ball shall be struck half-way up and before the club touches the turf. Therefore keep the eye steadily fixed upon that point (see the right-hand ball in[Pg 96] the small diagram on page 170) and come down exactly on it. This is not an easy thing to do at first; it requires a vast amount of practice to make sure of hitting the ball exactly at the spot indicated, but the stroke when properly made is an excellent and most satisfying one. After striking the ball in this way, the club head should continue its descent for an instant so that it grazes the turf for the first time two or three inches in front of the spot where the ball was. The passage of the club through the ball, as it were, is the same as in the case of the push shot with the cleek, and therefore reference may usefully be made to the diagram on page 106, which illustrates it. A natural result of the stance and the way the stroke is played is that the arms are more extended than usual after the impact, and in the follow-through the club head keeps nearer to the turf. So excellent are the results obtained when the stroke is properly played, that there are many fine players, having a complete command over it, who systematically play it from the tee whether there is a wind to contend against or not, simply because of the length and accuracy which they secure from it. Braid is one of them. If the teeing ground offers any choice of gradient, a tee with a hanging lie should be selected, and the ball is then kept so low for the first forty or fifty yards that it is practically impossible for the wind to take it off the line, for it must be remembered that even when the wind comes dead from the front, if there is the slightest slice or pull on the ball to start with, it will be increased to a disconcerting extent before the breeze has done with it.

When the wind is at the back of the player blowing hard towards the hole, the situation presents no difficulty and needs very little consideration. The object in this case is to lift the ball well up towards the clouds so that it may get the full benefit of the wind, though care must be taken that plenty of driving length is put into the stroke at the same time. Therefore tee the ball rather higher than usual, and bring your left foot more in a line with it than you would[Pg 97] if you were playing in the absence of wind, at the same time moving both feet slightly nearer the ball. Plate XXI. will make the details of this stance quite clear. The ball being teed unusually high, the golfer must be careful not to make any unconscious allowance for the fact in his downward swing, and must see that he wipes the tee from the face of the earth when he makes the stroke.

Though in my explanations of these various strokes I have generally confined myself to observations as to how they may be made from the tee, they are strokes for the driver and the brassy,—for all cases, that is, where the long ball is wanted from the wooden club under unusual circumstances of difficulty. Evidently in many cases they will be more difficult to accomplish satisfactorily from a brassy lie and with the shorter faced club than when the golfer has everything in his favour on the teeing ground, and it must be left to his skill and discretion as to the use he will make of them when playing through the green.